By Monique Taylor

As America was on the verge of entering World War II, the U.S. Army was in the process of developing an entirely new concept in aerial warfare—airborne forces. Airborne troops were defined by the Army as troops and equipment delivered to the battlefield via parachute or glider, while all other troops delivered by plane were classified as “air landed” troops.[1] An equally important, and often misunderstood distinction needs to be made between airborne troops and troop carrier forces which were organized separately. Troop carrier forces were defined as the “…air agencies for tactical, logistical and evacuation combat transportation, organized, equipped, and trained to transport troops and supplies by air.”[2]

The 1940’s doctrine of vertical envelopment was the precursor to our modern-day doctrine of vertical envelopment. It was the evolution of centuries of military use of ground envelopment tactics to defeat an enemy, applied to the advent of advancements in aerial technology of World War II. The Army defines envelopment as “…a form of maneuver in which an attacking force seeks to avoid the principal enemy defenses by seizing objectives behind those defenses allowing the targeted enemy force to be destroyed in their current positions.” [3]

The Germans were the first to deploy airborne forces in a major operation in 1940 to capture Fort Eben Emael in Belgium. Eleven German DFS 230 gliders, loaded with engineers/saboteurs, were released at an altitude of 8,000 feet and landed silently at the foot of the bridges crossing the Albert Canal and atop the turf roof of the fort. The German glider troops took the Belgian defender by surprise, and soon both the bridges and Eben Emael were in German hands, opening the gateway to France. To keep their use of gliders secret, Germany credited the fall of the fort to an infantry assault. No mention of glider involvement, or an additional secret weapon used by the glider troops—the shaped, or hollow, demolition charge— was mentioned by the Germans. The next major airborne operation, the German invasion of Crete, sounded the death knell for German airborne troops, as German paratroopers and glider forces suffered heavy casualties against British and Commonwealth defenders. While the Germans ultimately prevailed, the losses incurred on Crete convinced Adolf Hitler that gliders, and airborne forces in general, no longer provided an element of surprise, and therefore were no longer tactically advantageous as an offensive weapon.

The Waco CG-4A was the primary glider used by the U.S. Army during World War II. Nearly 14,000 CG-4As were manufactured during the war, and they were used in every major Allied airborne operation. (National Museum of the U.S. Air Force)

The United States and Great Britain continued where Germany left off, further developing the glider doctrine of vertical employment throughout the war. The Allies used the element of surprise the glider afforded when possible, and despite repeating some of the errors the Germans made in their use of gliders, they also refined both the glider and glider pilot roles to support action behind enemy lines.

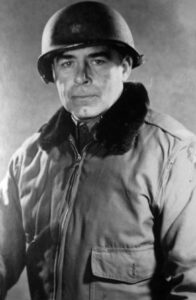

The American Glider Pilot Program was developed under the leadership of Lieutenant General Henry “Hap” Arnold, commander of the Army Air Corps (later Army Air Forces), and formalized on 25 February 1941. Unlike military glider programs in other countries, which fell under the infantry, the American glider pilot was organized under the Army Air Corps/Army Air Forces (AAC/AAF) and eventually was placed under Troop Carrier Command.[4] The Army developed the Glider Pilot Program entirely from scratch. It was without curriculum, tactical doctrine, a glider design, and pilots. The initial recruiting program was the 150 Glider Pilot Program which began in July 1941.[5] By 1943, within two years of its inception, trained glider pilots were flying as copilots to their British counterparts in the invasion of Sicily (Operation HUSKY) in August 1943, directly into the teeth of enemy antiaircraft fire with little evasive action possible.

The Air Corps initially intended to train powered aircraft (“power”) pilots as glider pilots. However, military power pilots could not be spared, therefore the criteria for potential glider pilots went through several revisions, with an initial emphasis on civilian-trained pilots.[6] As the quota of glider pilots required continued to rise to 8,000 then 10,000, military aviators and those without previous flight training either volunteered or were transferred to the Glider Pilot Program. The attraction for volunteers was the promise of rapid training, rapid advancement, potential officers’ commissions, good pay, and the ability to work towards a power pilot rating.[7]

In 1942, the program had two tracks: those with flying experience became Track A students, while those with no previous flying experience recruited when additional volunteers were needed became Track B students. Each track had a separate curriculum that corresponded with the students’ skills. In December 1943 and January 1944, the decision was made to reduce the number of graduating glider pilots and end the recruitment program. Many candidates were released, including Track B students who had not yet graduated.[8]

During the apex of glider pilot recruitment, the increasing need in all areas of the Army for additional manpower resulted in altered requirements for glider pilots and other military occupational specialties, particularly infantry. For a limited period, the age for glider pilot was raised to thirty-five, and the eyesight requirements for Class A students were lowered from 20/100 correctable to 20/20 with glasses. Those with power pilot experience were accepted if they had fifty hours flying in military or naval aircraft as a pilot or a student pilot. Some of these became the glider pilots that were later referred to as “power pilot” washouts. In reality, many recruits accepted to the program under the relaxed requirements had not completed their training due to program delays, and were released when the AAF made cuts to their program.

Glider pilot flight training took place in both civilian and military facilities. The bulk of the training between 1941 and 1943 took place at civilian training centers. These facilities were located in three regional areas: the Southeast, the Gulf Coast, and the West Coast.[9] The initial training center, established in August 1941 under the 150 Officer Training Program, was held at a private training field in New York run by the Elmira Corporation. Nine pilots trained there with the remainder training at Twentynine Palms in California. The program was quickly revised to the 1000 Glider Pilot Program in February 1942.[10] In April 1942, another upward revision to the quota of graduated glider pilots was raised to 4,200. The 4200 Glider Pilot Program called for additional training facilities to accommodate the expected number of trainees. Elementary Glider Schools opened between May and June 1942 at Lamesa Texas, Elmira New York (Elmira Corporation), and Wickenburg, Arizona.[11] Concurrently, planning was in the process for two Advanced Training Schools by June 1942. These changes and those to come to the Glider Pilot Programs reflected the growth, defining, and redefining of the rocky road of glider design and production.

As the expected need for glider pilots increased, on 8 May 1942, the 6000 Glider Pilot Program replaced the previous program, with the goal of graduating 3,000 glider pilots by September 1942.[12] To accomplish this, Preliminary Light Airplane Schools were to be established in Army Air Forces training jurisdiction regions, mainly through contracts with private companies. In the Southeast Air Forces Training Center region were Jolly Flying Service, Grand Forks, North Dakota; L. Miller-Wittig, Crookston, Minnesota; Hinck Flying Service, Inc., Monticello, Minnesota; Fontana School of Aeronautics, Rochester, Minnesota; North Aviation Company, Stillwater, Minnesota; Morey Airplane Company, Janesville, Wisconsin; and Anderson Air Activities, Antigo, Wisconsin. Under the Gulf Coast Air Forces Training Center region were McFarland Flying Service, Pittsburg, Kansas; Ong Aircraft Corporation, Goodland, Texas; Sooner Air Training Corporation, Okmulgee, Oklahoma; Harte Flying Service, Hays, Kansas; Anderson and Brennan Flying Service, Aberdeen, South Dakota; and Kenneth Starnes Flying Service, Loanoke, Arkansas. Under the West Coast Air Forces Training Center region were Plain Airways, Fort Morgan, Colorado; Cutter-Carr Flying Service, Clovis, New Mexico; Big Spring Flying Service, Big Spring, Texas; and Clint Breedlove Aerial Service, Plainview, Texas.[13]

The pilot and co-pilot of a CG-4A sit in the cockpit compartment of their glider. (U.S. Army Special Operations Command History Office)

Modified training had to be given to trainees in light planes, since military cargo gliders were not yet available. Some light planes had an average glide ratio of 26:1 which translates as for every twenty-six feet of glide there was a drop in altitude of one foot, which differed from an empty CG-4A glide ratio of 15:1. In July 1942 problems began to arise due to the shortage of training equipment which would continue to plague the program in the future. Furthermore, in July, the progression of the design and production of the combat glider necessitated a new curriculum which in turn necessitated training centers for training on combat-type gliders. The Elementary- Advanced School was established with previous glider pilot graduates serving as instructors. In addition to Twentynine Palms in California and the Elmira Company (now in Mobile, Alabama) already operating, the John H. Wilson Glider School at Bowman, Texas, and Arizona Gliding Academy in Wickenburg, Arizona, were opened.[14] In conjunction with those new training centers, additional Elementary-Advanced Training Program sites were opened in Amarillo and Waco, Texas, Lockbourne, Ohio, and Fort Sumner, New Mexico.[15] Further revised quotas were on the horizon while streamlining of the existing training programs continued. The Army now required all Preliminary Schools to accommodate 250 trainees with the remainder of schools to be closed. Shortly thereafter no new trainees were to be placed in the Preliminary Schools, and these graduates were to remain where they were until there was space for them in the Elementary and Advanced Schools.[16]

On 14 September 1942, a new training curriculum was established that required eight new Preliminary Schools; a total of eight Elementary Schools; eight Basic Schools, and five Advanced Schools.[17] The program established a sixteen-week training program with four separate stages. Effective 6 May 1942, the 6000 Glider Pilot Program was put into effect with the required future graduation date of March 1943. In August 1942, the program was revised upward another 1,800 glider pilots which required a total of 7,800, all in different stages of training to be graduated by 1 March 1943.[18] With this came additions to the number of Basic Schools, some of which never opened due to equipment shortages. The only schools that were opened were in Stuttgart, Arkansas, and Lubbock and Dalhart, Texas.[19]

Four months later, serious cuts to the program began reducing the glider pilot goal from 8,000 graduates to 4,000 in a matter of months.[20] To accomplish this the Preliminary Schools in the Southeast Command were shut. The Class B students were discontinued and all Advanced Training would then be at South Plains Army Air Base in Lubbock, Texas.[21] A shortage of gliders for training and backlogs in training programs further complicated matters. In February 1943, the Army decided to close all Elementary and Basic Schools within thirty days.[22]

Army officers inspect the wreckage of a CG-4A that crashed during training in Tennessee after the tow rope broke, 4 June 1943. In this case, both pilots parachuted to safety, but in many other glider accidents, the crews were not so fortunate. (National Archives)

Additional training and practice took place at Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base in North Carolina before the graduated glider pilots were transferred to their troop carrier group (TCG) assignments. The individual TCGs continued training of glider pilots assigned to them was dependent on the number of tow planes, tow pilots, and gliders available. Gliders flew at Bergstrom Air Field in Austin, Texas.; Dalhart Army Air Base in Dalhart, Texas; South Plains Army Air Field in Lubbock, Texas; Fort Sumner Army Air Field in Fort Sumner, New Mexico; Greenville Army Air Field in Greenville, South Carolina; Lockbourne Army Air Base in Columbus Ohio; Stuttgart Army Air Field in Stuttgart, Arkansas; Victorville Army Air Field in Victorville, California; and Sedalia Air Field in Knobnoster, Missouri.[23] Throughout the glider pilot training, the Army expected a washout rate of approximately thirty percent. Further attrition occurred by way of training accidents that resulted in serious injuries and deaths.

In contrast to flight training, the glider pilots’ combat training was not formally addressed by the command until November 1942, and only then in response to the disciplinary problems of those lingering for months in the glider training pools at Bowman Field, Kentucky.[24] As a result, in April 1943, the Glider Pilot Combat Training Unit at Bowman Field was set up to give intensive training on military subjects for glider pilot graduates.[25] Before this, glider pilots who were military members before entering the Glider Program already had some combat training. For civilians coming into the program, combat training was hit or miss. In seeking a solution, Troop Carrier Command left it to the TCGs to provide this training with little to no oversight. This changed on 3 April 1943, when a formal combat training course was established at Bowman Field while glider pilots trained there.[26]

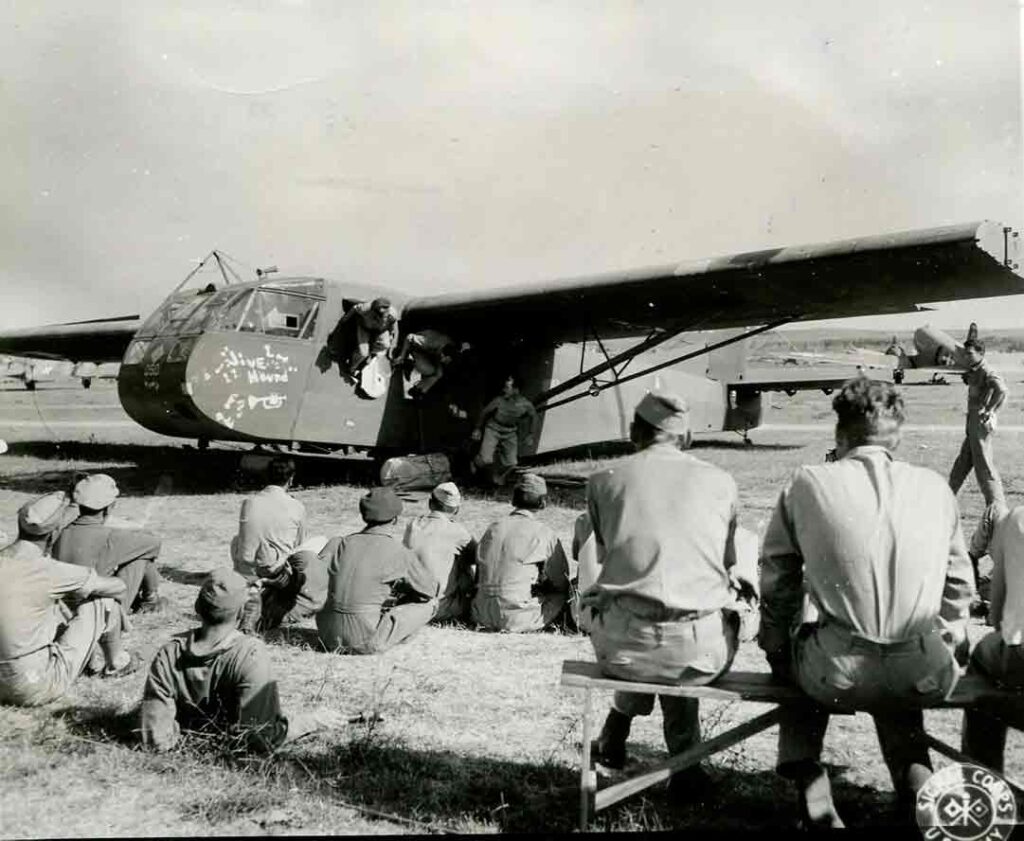

For some time, Flying Training Command graduated more glider pilots than the number of gliders available. As formal combat training was established more gliders began coming off the production line, making more available for trainees. While at Bowman Field, a training call went out for one hundred glider pilot volunteers for a secret mission. These volunteers were given an intensive specialized six-week combat training course in jungle warfare and assigned to the 1st Air Commando Group in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater. In the European Theater of Operations (ETO), some glider pilots received additional combat training at their overseas duty stations.[27]

Upon successful completion of their training, glider pilots were awarded their Glider Pilot’s Wings, approved by the Army in August 1942. (Image courtesy of David Kaufman)

In a major blow to morale, the Army broke many of the recruitment promises made to glider pilots. Rapid advancement, officers’ appointments, and power pilot ratings did not happen. The issue of rank was also a contentious one. Many glider pilots were promoted to staff sergeants upon acceptance into the program. In an attempt to make the glider pilot more of an officer, the rank of flight officer, in essence, third lieutenant, was made official. Most glider pilots remained at this rank throughout their wartime service because there were limited officer slots in Troop Carrier Command. In the ETO, glider pilots, although part of Troop Carrier Command, were often left to their own devices. It took time for them to be fully embraced into some of the TCGs. Many of the myths surrounding glider pilots categorizing them as old men, washed-out power pilots with poor eyesight, and mavericks stem from the growing pains of the Glider Pilot Program. Glider pilots were, in fact, skilled pilots and infantry soldiers, and excelled at improvising in any situation. It can be argued that theirs was a do-or-die occupation—those who did not rise to the top may not have survived the first mission. There was no official killed-in-action (KIA) list kept for glider pilots to determine the number that died in combat missions.[28]

A total of five glider missions were flown in the ETO after Sicily in the Mediterranean Theater: Operation OVERLORD, the invasion of Normandy, 6-7 June 1944; Operation DRAGOON, 15-16 August 1944, in southern France; Operation MARKET-GARDEN, 17-30 September, in Holland; Bastogne, 26-27 December 1944, in Belgium; and Operation VARSITY, 24 March 1945, near Wesel, Germany. Glider missions were also flown in CBI and the Southwest Pacific: Operation THURSDAY, 5 March 1944, in Burma, and Operation GYPSY TASK FORCE, 23 June 1945, in the Philippines by the 11th Airborne Division. It should be noted that GYPSY TASK FORCE was the only glider mission that employed the Waco CG-13 glider. The Army also conducted several smaller glider missions in CBI and Southwest Pacific.

The American Glider Pilot Program lasted only four short years and graduated between 6,000 and 7,000 pilots. During this time, a total of 13,903 gliders were manufactured and delivered to the Army.[29] Just as quickly as the Glider Pilot Program began it also ended. Gliders were superseded by helicopters by the time of the Vietnam War in the 1960s with much the same mission—land behind enemy lines to deliver troops and equipment, with the decided advantage of being able to power themselves out of the area after the delivery. Despite the wartime contributions of the glider pilots, somewhere between the end of World War II and the current day, their role as pioneers in what is now known as the doctrine of aerial vertical envelopment has been largely forgotten. Today they have become almost exclusively known for their unpowered aircraft and spectacularly tragic crashes.

Glider pilots and airborne engineers stand in the shade of a glider wing at an airfield in northern Burma as they wait for H-Hour for the assault on the Japanese-held airfield at Myitkyina, 17 May 1944. (National Archives)

Armies have employed the doctrine of ground envelopment/encirclement in many great battles throughout the centuries. Theoretically, in a true envelopment maneuver, the Allies in World War II operating in the ETO would have held an area at the front and then infiltrated or flanked the opposing forces and fought their way back towards the original line, fully encircling German formations and destroying them. This is where the initial implementation in World War II aerial vertical envelopment differed. Rather than surrounding the Axis forces, the Allies leapfrogged into the midst of enemy territory using paratroopers and disrupted communications, cut forces off, and fought to gain a foothold and hold the area. The full strength of the enemy would no longer be solely focused on the front lines. The Allies then repeated the movement further behind enemy lines, thus working towards the German border while securing additional ports and outlets to extend the critical supply line the further towards Germany they went. In the meantime, one of the great challenges the Allies faced in successfully implementing this strategy was successfully extending an immediate supply line to the paratroopers during the first few days. It could not extend it through the enemy-held territory they had leapfrogged over until it was in Allied hands and many of the railways, roads, and bridges repaired.

Any given mission was/is made up of many moving parts. A successful airborne drop or glider landing was a team effort. All flying personnel were assigned to TCGs, including the American glider pilots. On most glider missions in the ETO, the pilots designated to fly the first mission were to locate the correct drop zone (DZ) and drop the pathfinders. The pathfinders were the first elements of the airborne troops dropped via parachute behind enemy lines and given a short window of time to clear/mark DZs and set up the Rebecca-Eureka radar transponder system, to guide the pilots ferrying the paratroopers about thirty minutes behind them for drops. Once the DZs were secured, the pathfinders did the same for the landing zones (LZs) for gliders that followed the airborne troops. With the zones marked and the drops completed, the pathfinders located and fought with their units, other units, or on their own. The paratroopers landed with only enough equipment and supplies to fight for three days without resupply due to weight restraints on the jumps. After that window of time, they were dependent on resupply reaching them to be able to survive, continue to fight, and complete their mission. The gliders that followed them were that immediate resupply.

Resupply of the airborne by gliders could go on for hours or days, depending upon the situation on the ground. While the transport pilots returned to their bases, the glider pilots descended into a maelstrom of antiaircraft fire, sniper and mortar fire, and glider obstacles designed to destroy the glider, its cargo, and its occupants. Despite being organized under Troop Carrier Command, upon landing, the glider pilot immediately became infantry working with the airborne troops. This led to some difficult situations since glider pilots as flight officers or higher ranks often outranked the airborne infantry they transported. After much wrangling, it was decided the glider pilots were in command of the troops in their gliders until the cargo was unloaded. Glider pilots were the only AAF pilots assigned an additional infantry role. Their standing orders were to proceed to the command post where they guarded prisoners, fought alongside the parachute and glider infantry, served as runners, or set up defensive perimeters. Once released by the airborne commander, they were evacuated or returned to their home bases singly or in groups to be prepared to fly in additional supplies if required.

The Waco CG-4A (known by the British as the Hadrian) was the workhorse of the American glider program. Its design allowed for a large variety of cargo in the interior with a payload of 3,750 pounds.[30] The CG-4A had a fuselage that was forty-eight feet long and constructed of lightweight steel tubing. The wingspan was 83.6 feet and was constructed of lightweight plywood attached to a wooden frame.[31] The entire glider was covered in a linen-cotton fabric to which multiple coats of a chemical compound called dope were applied. Once applied it would shrink the fabric around the fuselage and wings and provide a protective coating against the elements. However, it was extremely flammable. The glider had no defensive capabilities and no armor to protect the occupants from antiaircraft fire.

A damaged glider supporting the 82d Airborne Division rests in a field near Sainte-Mère-Église, France, after a rough landing, 12 June 1944. (National Archives)

The cockpit on the CG-4A was hinged and could be lifted up out of the way for loading or unloading cargo. The hinged cockpit also served as an emergency prevention against glider pilots being crushed by large cargo such as jeeps or bulldozers breaking loose upon landing. Such heavy equipment was carefully balanced in the glider and secured. A pulley system rigged to the rear of the heavy equipment extended up and over along the ceiling of the glider to the cockpit. If the equipment broke its lashings and shot forward, the pulley system would raise the cockpit lifting the glider pilots out of the way as the equipment exited underneath them. This safety feature was useless if the glider pilots could not release the lever to allow the cockpit to swing up or if the cockpit was prevented from opening by an impediment to the nose of the glider such as a hedgerow or other embankment.

With a descent ratio of 400 feet per minute and a landing run of 600 to 800 feet, the CG-4A was ideal for landing its cargo and troops in small fields. Of course, every factor depended upon the balance and final weight of the glider with a reduction in glide ratio and stopping distances expected with a heavier the load. Ground conditions also played a major role in the success of the landing. Two CG-4As could be towed in tandem allowing for 7,500 pounds to be delivered to the battlefield behind one tow plane, with the obvious reduction in the range of the C-47. Double tows of gliders were done in both the ETO and the Asiatic-Pacific Theater.

Glider operations were mission and theater-of-operation specific. Both the ETO and the Asiatic-Pacific Theater were distinct in their geography and military objectives. Gliders in CBI were organized under the 1st Air Commandos. Initially, their cargo consisted of engineers, bulldozers, scrapers, radio equipment, gasoline, and other building supplies delivered to small openings in the jungle to construct or repair airstrips. They also crossed enemy-held territory to deliver troops, mules, weapons, and supplies to wage unconventional warfare on the Japanese in the jungle once the airstrips were built.[32] Once the airstrip was large enough, C-47s could bring in additional cargo and men. For the wounded, gliders served as portable hospitals and operating rooms in CBI; as an additional bonus, the interiors of the gliders could be set up with the secured litters to enable evacuation of the wounded via a snatch-up maneuver. Simplified, a C-47 flew overhead and “snatched” a cable connected between two poles and connected to the glider, hauling it into the air at speeds around 120 miles per hour. The ability to evacuate the wounded via gliders and light planes solved a major issue and provided a morale boost for the men.

Pathfinders were not dropped in one major CBI mission to mark the landing zones (LZs) for gliders. In Operation THURSDAY, two gliders were towed to the LZs carrying smudge pots and signaling equipment and released.[33] Once landed, they placed the smudge pots and other visual aids to guide incoming gliders. Jungle landing strips were unlike the congruent fields of the ETO; often the small strip was the only clear area to land on. Gliders quickly had to be pushed to the side to clear the landing strip for the gliders descending for a landing right behind them. Once unloaded, glider pilots fanned out immediately to guard the perimeter, helped clear gliders off the fields, and performed other duties.

During preparation for Operation DRAGOON, the invasion of southern France, Instructors at Galera Airdrome near Rome, Italy, teach glider pilots how crash out of a glider in case they need to ditch in the Mediterranean Sea, 12 August 1944. (National Archives)

In both theaters of war, the gliders’ mobile supply line was tailored to the individual needs of each mission. This was a critically needed asset that cannot be overstated. In the ETO, gliders carried troops, jeeps, 75mm and 105mm howitzers, weapons, motorcycles, radios, medical equipment and supplies, ammunition, gasoline, survey equipment, water, rations, lumber, and other materiel. Glider cargo was limited only by weight and imagination. The beauty of the glider and its cargo-carrying capacity was further valued by the ability of gliders to land close to one another on assigned LZs, providing troops and equipment combinations ready for action almost immediately. As an example of the precision that was possible, two gliders, one with a jeep and one with an artillery piece and glider artillerymen, could land next to or near each other on the LZ. The gunners could quickly attach the howitzer to the jeep and the gun crew would be off and in action within thirty minutes. This was a decided advantage over parachuted equipment, which had to be located, gathered, and assembled before being brought into action.

The contribution the glider pilots made to the missions they were involved in is evidenced by the numbers compiled by the Troop Carrier Command Operational Summaries. Five missions in the ETO provide a clear snapshot of the number of gliders used in each one and the variety of equipment delivered. In Operation OVERLORD, a total of 512 gliders were dispatched with all but nine reaching their objectives. Considering the deteriorating conditions, poor visibility, and heavy antiaircraft fire, troop carrier pilots towing them encountered once they hit the French coastline, this was a very small percentage of those not reaching the assigned LZs. Many tow pilots were injured or lost their lives in their determination to give the glider pilots the best chance possible to land where assigned. Glider pilots successfully delivered 4,047 troops, 281 jeeps, 110 artillery pieces and antitank guns, 280 gallons of gasoline, 10,355 pounds of mines and explosives, 202,062 pounds of ammunition, 5,672 pounds of rations, and 194,388 pounds of other combat equipment to the airborne troops.[34] In OVERLORD, forty-four glider pilots were killed and more than twenty wounded.[35]

The invasion of Normandy was followed shortly after by Operation DRAGOON in southern France. Three hundred and sixteen gliders were dispatched with only four landing outside their objective. DRAGOON was a significantly smaller mission than OVERLORD with smaller numbers of vehicles, weapons, and supplies carried by gliders: 175 jeeps, with fifty-nine howitzers and antitank guns, 400 gallons of gasoline, 1,000 pounds of mines and explosives, 191,046 pounds of ammunition, 11,483 pounds of rations, and 216,180 pounds of other combat equipment, in addition to 2,235 troops.[36]

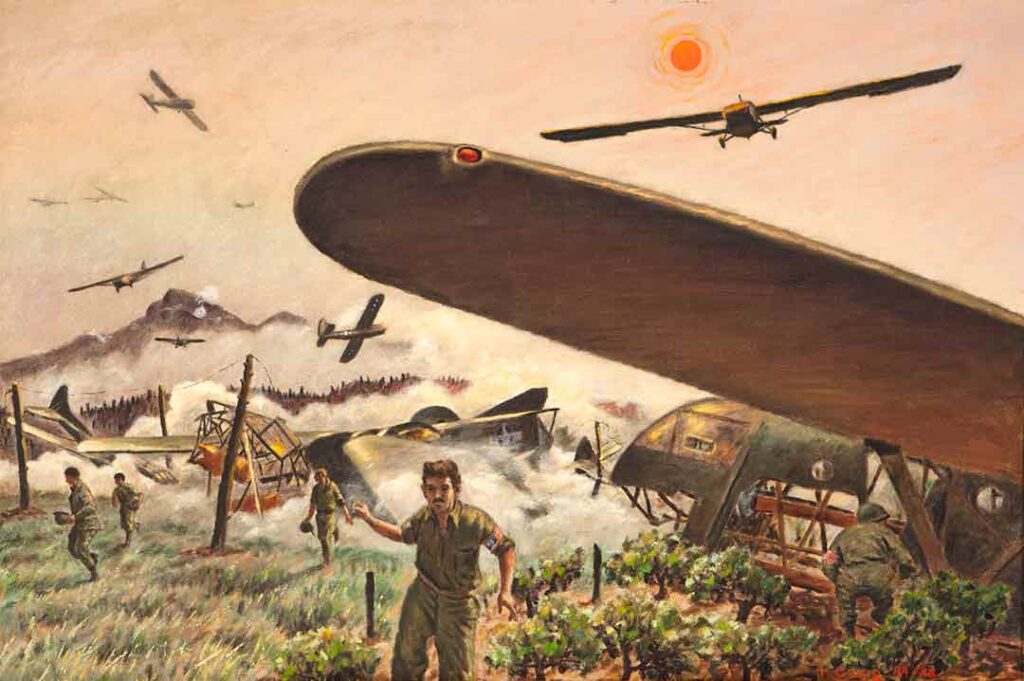

During DRAGOON, several glider crew casualties were caused by poles planted in the fields designed to cause damage to the gliders. Many French farmers who were forced to plant the poles buried them shallowly so they would tip over when hit by a glider, minimizing any damage or injuries. However, many of the grape supports in the local vineyards had not been removed as planned, and this caused major damage to the gliders and injuries to the glider occupants. The casualty rate among glider crews for DRAGOON was significant, with twenty-three glider pilots killed and over sixty wounded.[37]

Tom Craig’s 1944 oil on canvas, Glider Landing in Southern France, depicts the chaotic glider landings in support of Operation DRAGOON in mid-August 1944. (Army Museum Enterprise Art Collection)

In contrast to Operation DRAGOON, Operation MARKET GARDEN, a combined airborne and ground assault into the Netherlands launched on 17 September 1944, was a much larger mission. American and British forces employed 1,899 gliders with 1,635 landing on the assigned landing zones. The number of glider infantry delivered to their landing zones accompanied by their full equipment totaled 9,566 from the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions, with more glider troops deployed from the British 1st Airborne Division. An additional 1,432 glider infantry did not reach their objective. Gliders brought in 705 jeeps, 185 artillery pieces and antitank guns, and two million pounds of other equipment, ammunition, and supplies.[38] MARKET GARDEN was a tough mission for the airborne and took its toll on the glider pilots as well, with forty killed, thirty-seven wounded, and sixty-five missing or taken prisoner.[39] Glider pilots who took part in MARKET GARDEN from the 61st and 313th TCGs, with the 316th as a mobile reserve, went on to serve on the front lines for several days until ground forces from the British XXX Corps reached them. Upon evacuation, the glider pilots found themselves under fire again when the convoy they were riding in was ambushed on the way out from Veghel. Taking protection in ditches they eventually detached the trailers and inched the trucks and equipment out of the line of fire, saving fourteen of the seventeen trucks in the convoy.[40] Two pilots from the 313th TCG were listed as missing and one was wounded in the ambush.[41]

A few months later the 101st Airborne Division found itself in dire straits in Bastogne during the German operation Wacht am Rhein, commonly known as the Ardennes Offensive, the Ardennes-Alsace Campaign, or the Battle of the Bulge. The Allies had been unable to provide aerial support or deliver supplies and equipment for eight days to the already short-supplied troops holding the key town of Bastogne, Belgium, because of poor weather conditions. The 326th Airborne Medical Company, supporting the 101st Airborne, had been overrun by the Germans, and their medical personnel and patients were captured or killed.[42] The loss was compounded by an inability to evacuate the critically wounded from the Bastogne area. To remedy this, airborne planners devised a mission to bring in medical personnel and supplies to assist the beleaguered troops holding Bastogne. On 26 December 1944, two missions totaling eleven gliders were flown and successfully delivered nine medical personnel, including critically needed surgeons, medical equipment, and 32,909 pounds of combat equipment and supplies. Included in that total were artillery rounds and approximately sixty cans of 80-octane gasoline.[43]

A similar mission attempted on the following day, however, was not as successful. Out of fifty gliders dispatched, all without co-pilots, only thirty-five made it to their objective.[44] This was due in large part to intelligence personnel failing to notify the pilots of a different flight corridor under American control that was open and secure for flights. Due to this failure, the glider pilots and their tow aircraft ran into heavy antiaircraft fire flying through the same corridor used the day before. The losses meant only 106,291 pounds of the 151,831 pounds of cargo dispatched that day made it through to the LZs.[45] Four glider pilots lost their lives and eighteen were wounded.[46]

The numbers reported for these four missions highlight the significance of the glider pilots’ role in the successful initial application of vertical employment tactics in the war. Flying over the enemy, through intense antiaircraft fire, they then further aided in its success by assuming an infantry role upon landing. Their contributions assisted the airborne in gaining the positional advantage by seizing territory, sowing confusion, and destroying enemy forces and their supply lines. This could not have been achieved without the amounts and variety of cargo, troops, and equipment the glider pilots delivered. It was critical to ensure the supply line continued to both the airborne and ground troops, without which the territory they gained may not have been held.

Glider crews who will fly soldiers, equipment, and supplies for the 101st Airborne Division gather for a photograph around a CG-4A before they take off for Holland in Operation MARKET-GARDEN, 18 September 1944. (National Archives)

The glider tactics and glider pilot’s mission continued to evolve up and through the last glider mission in the ETO, Operation VARSITY. This operation took place on 24 March 1945 with the paratrooper and glider forces making another aerial leap, this time across the Rhine River and into the German heartland. One of the main objectives of the mission was to enable Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group to cross the Rhine River. There were many firsts in this mission for the glider portion. The 314th TCG was, for the first time in the war, towing its own glider pilots. In every other mission, the 314th TCG glider pilots were on detached service, often flying with unknown tow crews. Pathfinders were replaced with the U.S. Army Air Forces glider combat control teams, self-sustaining detachments arriving in six gliders and tasked with establishing and maintaining communications, as well as performing much of the same tasks as the Army pathfinders with the most advanced communication and navigational aids.[47]

During VARSITY, power pilots served as glider co-pilots. Upon landing, the glider pilots formed an all-officer infantry company in the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment, 17th Airborne Division; during a dramatic moment of the operation, the company repulsed a German counterattack in what became known as the “Battle of Burp Gun Corner.” The glider landings were on the whole very accurate and allowed the airborne troops to move quickly into action with their equipment once they had eliminated enemy resistance on the LZs.[48]

Operation VARSITY employed 908 gliders with 885 landing on their assigned LZs. The number of troops delivered from the 17th Airborne Division to their LZs accompanied by their full equipment totaled 4,810 with 343 jeeps, 191 trailers/carts, ninety-nine mortars and artillery pieces, 390 gallons of gasoline, 71,423 pounds of mines and explosives, 393,690 pounds of ammunition, 20,278 pounds of engineering materiel, 32,632 pounds of medical supplies, 22,943 pounds of rations, and 1,484,081 pounds of other equipment.[49]

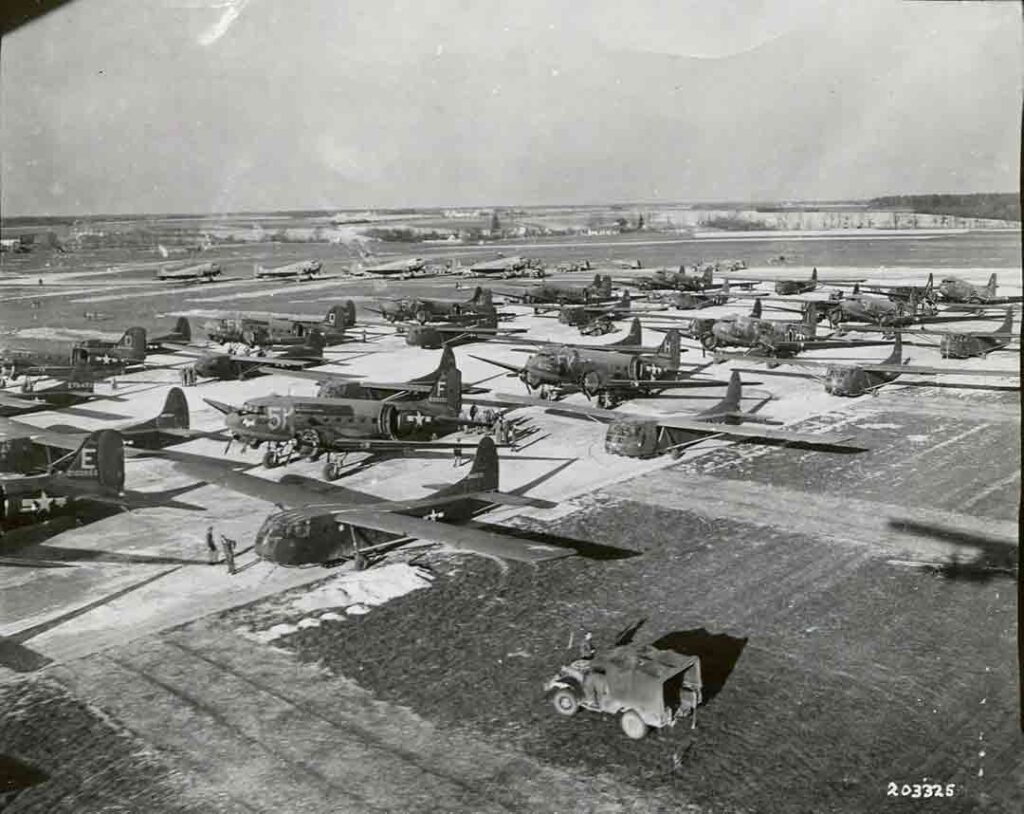

C-47 tow planes and CG-4A gliders line up in a marshaling area at a French airfield to take off for Operation VARSITY, an airborne assault across the Rhine River near Wesel, Germany, 23 March 1945. (National Archives)

Glider pilot after action reports give insight into difficulties that arose in VARSITY. Due to drifting smoke caused by the preemptory aerial and artillery bombardment, many glider pilots did not have visuals of the LZs until 500 to 600 feet. They could not see the German gun positions and snipers in the buildings surrounding some of the LZs. Conditions in each landing zone were different. On some, gliders were in full view and easy targets for the Germans as they flew through the haze for landing. Those that landed close to buildings were hit hard with sniper fire. To some, it seemed as if the Germans were aware of the LZs ahead of time. Others stated the LZs needed to be cleared by the airborne before the gliders arrived. Considering the loads they carried, there was good cause for concern as some of the gliders were essentially flying bombs.

After the last glider mission, several glider pilots stayed on and were part of the Flying Pipeline, operating as Troop Carrier Command co-pilots in bringing supplies in and prisoners of war out of Germany. Others remained in the Army, or later the Air Force after it became an independent service in 1947 and became pilots serving in Korea and Vietnam; many became career military officers. The full legacy of glider pilots and their contribution to World War II is still largely untold eighty-four years later but has its foundations first and foremost in a correct understanding of their role both as pilots and infantrymen and their role within the airborne mission. Any study of the airborne forces of World War II without an equally in-depth analysis of the ability to complete said mission due to glider/glider pilot support is incomplete.

About the Author

Monique Taylor is the author of Suicide Jockeys: The Making of the WWII Combat Glider Pilot published in November of 2023 by Koehler Book Publishing. She holds a B.A. in English Literature, an M.A. in Modern European History, and a Juris Doctor degree. She is also the youngest daughter of a World War II glider pilot. She lives the foothills of California with her husband a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel and is currently researching her second book on the glider pilots’ mission to Bastogne.

Endnotes

[1] Army Air Forces (AAF) Tactical Center, “Troop Carrier Aviation,” Captain Wasson J. Wilson. (200-5-14-L), Orlando, Florida AAF School of Applied Tactics, December 1943, 6.

[2] AAF Tactical Center, “Troop Carrier Aviation,”1.

[3] U.S. Army, Fort Moore, U.S. Army Infantry School, “Form of Maneuver,” https://www.moore.army.mil/Infantry/DoctrineSupplement/ATP3-21.8/chapter_04/section_02/page_0040/index.html

[4] Executive Order 9082, February 1942 “Reorganizing the Army of the United States and Transfers of Functions within the War Department” placed both Combat Command and the Air Corps under the Army Air Forces.

[5] Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Intelligence, Historical Division, “Army Air Forces Historical Studies: No. 1,” Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell AFB, September 1943, 7.

[6] Note: The Air Corps was not initially under the command of the Army Air Corps.

[7] According to Paul W. Mousseau, World War II glider pilot, the military would not allow count the hours glider pilots flew as copilots on transport planes towards there rating because they were accumulated during wartime. Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Mousseau, USAF-Ret., glider pilot of the 32d Troop Carrier Squadron 314th Troop Carrier Group, interview by author 20 June 1989, Fresno, California.

[8] Due to backlogs in the training programs many of the Class B students who were recruited or volunteered when standards were reduced had not graduated by this time and were released from the program. Lieutenant Colonel Mousseau interview, 20 June 1989.

[9] AAF Historical Studies, 19.

[10] Ibid, 11.

[11] Ibid, 16.

[12] Ibid, 18.

[13] Ibid, 19.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid, 20.

[16] Ibid, 33.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Note: Multiple revisions to the program took place before trainees recruited under previous revisions could be graduated. At one point the cumulative total of prospective graduates was 10,000.

[19] AAF Historical Studies No. 1, 39.

[20] Ibid., 45.

[21] Ibid, 62.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Major Leon Spencer, USAF-Ret.,, “US Army Air Force CG-4A Combat Glider: A Brief History,” WW2GP Blogspot, October 2014, https://ww2gp.blogspot.com.

[24]Note: Glider training took place at Bowman Field in addition to glider pilot combat training.

[25] AAF Historical Studies No. 1, 79.

[26] Those that graduated and had pinned their Glider Pilot Wings were disgruntled when they were ordered to take them off and attend the Advanced School. Lieutenant Colonel Mousseau interview, 20 June 1989.

[27] Glider pilots with the 314th TCG in North Africa were given training with the 82d Airborne Division; Lieutenant Colonel Mousseau, interview, 20 June 1989.

[28] Likewise, the author has been unable to locate any official list of glider pilot trainees killed in training. It is important to note that they were not considered glider pilots under graduation. The washout rate for trainees was quite high.

[29] Spencer, “U.S. Army Air Force CG-4A Combat Glider: A Brief History.”

[30] James E. Mrazek, Fighting Gliders of World War II (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1977), 111.

[31] Ibid, 111.

[32] Monique Taylor, “The Flying Mules of Burma.” National World War II Glider Pilot Association, Briefing, https://www.ww2gp.org/burma/FlyingMulesCBI.pdf.

[33] 1st Air Commandos, JICA/CBI, Report No. 1834, BO680 GP CMDO -1- HI 12/ 44, Appendix F.

[34] Headquarters, IX Troop Carrier Command, Statistical Control Office, Consolidated Tactical Operational Summary Operations Neptune – Dragoon – Market.

[35] Major Leon Spencer, USAF-Ret., “They Flew Into Battle on Silent Wings: World War II Glider Pilots of the US Army Air Force,” WW2GP Blogspot, https://ww2gp.org/pdf/TheyFlew_into_BattleSilent_on_Wings.pdf, 4.

[36] Headquarters IX Troop Carrier Command, Consolidated Tactical Operational Summary Operations Neptune – Dragoon – Market.

[37] Spencer, “They Flew Into Battle on Silent Wings,” 4.

[38] Headquarters, IX Troop Carrier Command, Consolidated Tactical Operational Summary Operations Neptune – Dragoon – Market.

[39] Spencer, “They Flew Into Battle on Silent Wings,”4.

[40] Market September ’44, Factual Glider Report, Serial A-38 313th Troop Carrier Group, 33, 313th TCG, RG 18, Entry #7, Federal Records Center, Suitland, Maryland.

[41] Market September ’44, 33.

[42] Dr. Grant Harward, “Encircled At Bastogne: A Case of Prolonged Care,” Infantry Online,” Winter 2021-2022, https://www.moore.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2021/Winter/pdf/12_Harward.pdf

[43] Headquarters, IX Troop Carrier Command, Consolidated Tactical Operational Summary Bastogne – Belgium; Spencer, “U.S. Army Air Forces CG-4A Combat Glider: A Brief History,” 17. Spencer also states three surgeons, and four medical personnel were killed in gliders from the ground fire. The Tactical Operation Summary only states how many arrived at their objective. The National WWII Glider Pilot Association states each glider carried 300 gallons of 80 octane gasoline in on the 26 December 1944 mission.

[44] Headquarters, IX Troop Carrier Command, Consolidated Tactical Operational Summary Bastogne – Belgium.1; Spencer, “US Army Air Force CG-4A Combat Glider: A Brief History” states glider pilots and passengers were issued parachutes in a break from normal procedure on this day’s mission.

[45] Headquarters, IX Troop Carrier Command, Consolidated Tactical Operational Summary Bastogne – Belgium.

[46] Spencer, “They Flew into Battle on Silent Wings,” 4.

[47] Combat Control School Heritage Foundation, U.S. Air Force Special Tactics: Combat Control Team History 1945-2020 (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2022), 53.

[48] Alan Wood, History of the World’s Glider Forces (Sparkford, UK: Patrick Stevens Ltd., 1990) 265.

[49] Headquarters IX Troop Carrier Command, Statistical Control Office, Operation “VARSITY,” 24March 1945,Collection ofSilent Wings Museum 2002-10-28, Operation VARSITY Report.