Written By: Nick Reynolds

(National Archives)

The U.S. Army has a long history of employing animals in various missions. From the oxen-drawn sleds of the Knox Expedition dragging cannon from Fort Ticonderoga to Dorchester Heights outside of Boston in 1776, the Camel Corps experiment in the Southwest during the mid-nineteenth century, the Army’s long history with horse cavalry, to the use of dogs in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, animals and the Army have long been intertwined. One animal that had a relatively brief but important role in the Army was the lowly pigeon, specifically the homing pigeon (Columba livia domestica), with its unusual ability to be trained for long-distance flights to and from specific points.

Pigeons were first domesticated well over 5,000 years ago, potentially as long as 10,000 years ago, and used for the purpose of communication by the ancient Egyptians as early as 3,000 BC. The pigeon traveled with European settlers to North America early in colonial history. These early American pigeons, however, were mostly used as an easy source of food. Ironically, it was not until after the invention of such quick and long-distance methods of communication as the telegraph and the telephone that the U.S. military began seriously considering their use as messengers.

The telegraph was a revolutionary invention in 1837 and was immediately pressed into military service, but it had several serious drawbacks as a communication method. For one, it required a physical line from machine to machine. While wire was cheap, rolling out miles of wiring between the front and command posts presented problems. Artillery or enemy raids frequently severed lines, leaving commanders reliant again on couriers to and from their deputies or on personal trips to the front. The Civil War featured several famous Confederate raids into Union-occupied territory that cut telegraph lines, leaving Washington in the dark as to the fate of its armies. Additionally, a telegraph line could be physically “tapped” into, allowing enterprising enemies to listen in on communications.

All of those concerns, plus the extensive use of pigeons in Europe during the Franco-Prussian War, led to some experimentation by the Signal Corps in 1878. Then-Colonel Nelson Miles, stationed in the Dakota Territory, was conducting experiments with heliographs for communication and was sent some homing pigeons by the Signal Corps. A report four years later concluded the birds were “unreliable.” A pigeon station was established by the Signal Corps on Key West, Florida, in 1888, but that too closed after four years. These small-scale experiments left negative impressions on the Army before they gave up on the idea and handed it off to the U.S. Navy. The Navy, whose use of the telegraph was more limited than the Army, made use of pigeons for communications through the 1890s.

A subsequent Army effort was made during the Punitive Expedition in Mexico, which was a high-mobility affair using trucks and cavalry to chase irregular Mexican bandit groups through the hostile terrain of northern Mexico. Nevertheless, this effort, as with most of the Punitive Expedition, failed to achieve sufficient success.

It was only after the United States entered World War I that the Signal Corps fully realized the use of pigeons in combat. World War I did not have the same potential for enemy raids cutting or tapping into telegraph lines that occurred during the American Civil War, but the destructive impact of explosive artillery rounds was a hundredfold worse than what the Army had ever experienced.

Units at the front routinely had their lines destroyed by artillery, and couriers running back and forth from the front were similarly in danger from artillery, machine guns, or gas attack.

The timely delivery of coordinates for indirect fire support was more vital than ever before, and the Army needed a reliable and faster system of information delivery. The radio was still in its infancy, and radio sets were too few and too cumbersome for use at the front to fill the information gap. General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, recommended the creation of a pigeon service in July 1917, shortly after his arrival in Europe and witnessing the French and British homing pigeon services at work. French signal officers particularly had positive experiences using pigeons as couriers. During the Battle of Verdun in 1916, “pigeons established a record of efficiency between 97 and 98 percent, and frequently were the only means of communication between the ‘zone of advance’ and the rear echelon.”

Seeing the success that the Allies had with pigeons, the Adjutant General of the Army authorized the creation of the U.S. Army Pigeon Service. On 29 October 1917, 800 pigeons were part of a major American military shipment to Europe, traveling on the USS Agamemnon and arriving on 12 November.

It is important to note how the Signal Corps had to create the facilities, processes, and recruit personnel completely from scratch in the fall of 1917.

The Army had limited experience resulting from the use of pigeons during the Punitive Expedition, but nothing that could be truly scaled up to support an effort that World War I required. In 1917 the U.S. Army Pigeon Breeding and Training Center began operations and would be based at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, until 1957, with a brief interlude where the center was based at Camp Crowder, Missouri, from 1943 to 1946.

The exact training methods and reasons why homing pigeons behave the way they do is fascinating. The practice takes advantage of two factors: the bird’s strong desire to return home to its original loft, and the bird’s innate sense of direction and orientation allowing it to return there when removed long distances from it.

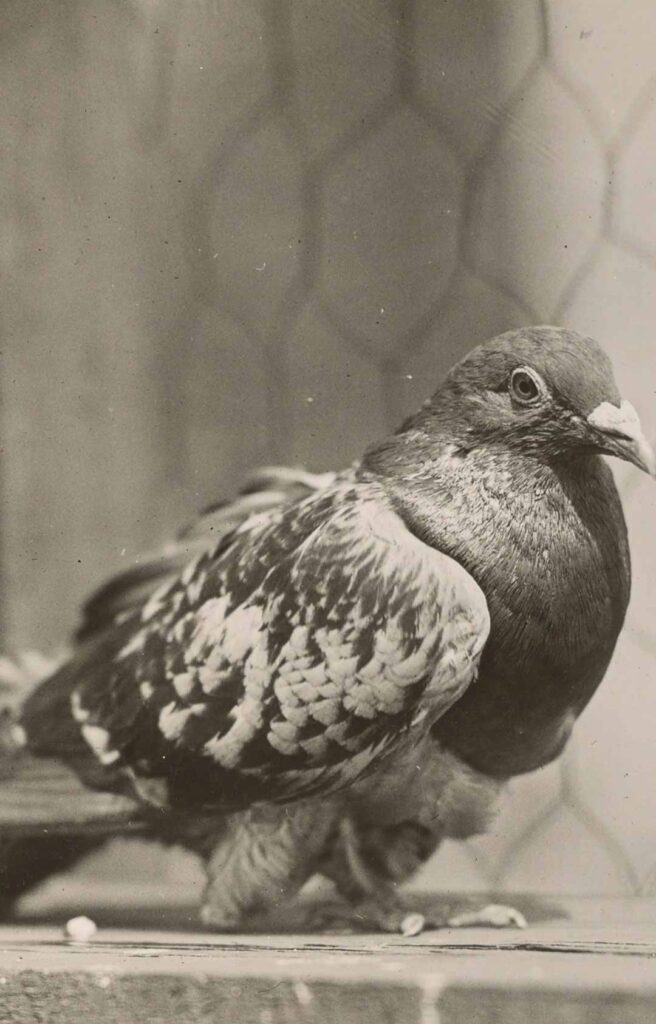

Lofts were typically stocked with young birds who then essentially imprinted their surroundings as their home. The stock chosen for signal companies was picked carefully, with Signal Corps First Lieutenant Carter W. Clarke noting that “homing pigeons bear the same relation to ordinary pigeons that a carefully bred high-strung racing horse bears to a dray horse.” Such care in the selection of birds was important, as training individual birds was an investment not just in the bird but also in time between handlers and birds.

Training of the pigeons began as soon as they were acquired. The birds were fed a delicious (to them) mixture of corn and peas that they rapidly associated with home and their loft. Then when the bird was about three weeks old, they were taught how to “trap” or re-enter the loft. This was done by coaxing them with the rattle of their tin feed can, and when the bird was back in the loft they were immediately fed.

This Pavlovian response to re-entering the loft was the principal means of training the pigeons. After twelve weeks, training for greater and greater distances began.

To acquire nighttime flying birds, pigeons were bred specifically for their proclivity for flying at night. Typically, night birds were selected after three generations of birds had shown promise in night flying. Their training was similar to the daylight birds, except that the training began at dusk, and then successive sessions occurred later and later until the birds were doing all their flying back to the lofts at night.

In order for the pigeons to carry messages, tiny tubes, PG-14 message holders, were tied to one of the bird’s legs. The sender wrote the dispatch on a small scroll of rice paper, rolled it up, and inserted it into the tube. The Signal Corps experimented with tubes tied across the breast of the bird, but these impeded the natural movement of the wings so this method was quickly abandoned. During World War I, several birds became “hero pigeons,” performing actions that resulted in saving the lives of American or Allied servicemen.

The most famous of these is probably Cher Ami, a pigeon attached to the 77th Division’s “Lost Battalion” of nine companies, under the command of Major Charles Whittlesey, encircled in the Argonne Forest in October 1918. The pinned-down Americans only had pigeons and runners for communications, which were proving quite unreliable due to their difficult circumstances. Down to their last bird, Cher Ami, they released her with the message, “We are along the road parallel to 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake, stop it.” Cher Ami was hit and fell to the ground, but then he rose up and finished his flight while badly wounded.

The American artillery ceased, and the next day accurately fell on the Germans. Cher Ami received the Croix de Guerre and the gratitude of General Pershing, who reportedly said, “There isn’t anything the United States can do [that is] too much for this bird.”

During the Meuse-Argonne offensive, 442 American pigeons delivered 403 messages spanning distances up to fifty kilometers (thirty-one miles) without a single lost dispatch. The Signal Corps’ use of pigeons was not limited to the European conflict.

The Army constructed lofts throughout the United States and its overseas territories, including the border with Mexico, the Panama Canal Zone, Hawaii, and over a dozen at coast artillery posts on both the East and West Coasts. By the time the Armistice ending World War I was signed on 11 November 1918, there were over 100 lofts housing over 10,000 pigeons operating throughout the United States.

Despite the Pigeon Service continuing beyond the end of World War I for several more decades, the growing capabilities of wireless radios began to sideline the need for pigeons in combat. Some noted examples of Army Pigeon Service use still occurred in World War II, including the famed flight of a pigeon named G.I. Joe which saved lives in the British 169th Infantry Brigade in Italy. On 18 October 1943, after British troops captured the village of Calvi Vecchia ahead of schedule, they could not call off a planned air raid on the village. As a last resort, G.I. Joe was dispatched and reached the airfield before Allied aircraft took off on the raid, preventing what could have been a deadly friendly fire incident. G.I. Joe would be awarded the Dickin Medal, considered the Victoria Cross for animals, by the British in 1946 and was the first non-British animal awarded the medal.

The last pigeons in Army service remained at Fort Monmouth until 1957 when the Army shut down the Pigeon Service.

Fifteen “hero pigeons” were donated to zoos across the country and hundreds of pigeons were sold to the general public.

Today, some of the Army’s hero pigeons are on display or in the collections of various museums, including Cher Ami, on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American History in Washington, DC, and Mocker, featured in the National Museum of the U.S. Army’s Nation Overseas Gallery.