Written By: Matthew Seelinger

During the Cold War, as the U.S. Navy and Air Force maintained America’s strategic nuclear arsenal of long-range bombers and submarine and land-based ballistic missiles, the Army focused on the development and deployment of tactical nuclear weapons for possible use on the battlefield. Beginning in the early 1950s, the Army introduced a wide range of unguided rockets, guided missiles, artillery shells, demolition charges, and other systems capable of carrying nuclear warheads, with yields ranging from a fraction of a kiloton to a few megatons. Among the smallest of the weapons in the Army’s nuclear arsenal was the M28/M29 Davy Crockett, a recoilless rifle system operated by a three-man crew and entering service in the early 1960s.

The development of nuclear weapons during World War II, and their use against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, ushered in a new, and potentially cataclysmic, age of warfare. Whole cities could now be destroyed in a matter of seconds by a single weapon. Some military planners believed that expensive, large-scale ground armies were now all but obsolete, as nuclear bombs provided “more bang for the buck.” However, the early versions of these weapons were primarily for strategic use. The two devices dropped on Japan, the “Little Boy” and the “Fat Man,” were large, cumbersome weapons, each with a weight of over 10,000 pounds and a length of approximately ten feet. Only the B-29 Superfortress had the capability of carrying and dropping these bombs, and they had little tactical use on the battlefield.

By the early 1950s, advances in nuclear weapons development, spurred by the Cold War and the Soviet Union’s detonation of an atomic bomb in 1949, allowed for great reductions in the size and weight of nuclear warheads. As a result, the Army began developing and deploying tactical nuclear weapon systems in Europe, beginning with the M65 “atomic cannon” capable of firing nuclear shells weighing 600-800 pounds, with yields of fifteen kilotons. This was followed by nuclear-tipped Corporal and Honest John missiles.

With the size of atomic warheads shrinking, and with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s growing reliance on tactical nuclear weapons to offset the Soviet Union’s huge advantage in conventional forces, the Army’s Ordnance Corps began looking at new weapon systems for use on the nuclear battlefield, including ones capable of being operated by small groups of front-line infantrymen. For Ordnance officials, the ideal system would be an easily transportable weapon carrying a simple nuclear warhead with a sub-kiloton yield, and having a range of 500 to 4,000 yards.

In late 1957, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), the government agency responsible for developing nuclear weapons, announced that it had successfully created a lightweight sub-kiloton yield fission warhead that could be used as a front-line weapon. AEC subsequently turned the responsibility of incorporating the warhead into a weapon system over to the Army’s Chief of Ordnance, Major General John H. Hinrichs. Work on the project commenced at Picatinny Arsenal in New Jersey in January 1958.

In late 1957, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), the government agency responsible for developing nuclear weapons, announced that it had successfully created a lightweight sub-kiloton yield fission warhead that could be used as a front-line weapon. AEC subsequently turned the responsibility of incorporating the warhead into a weapon system over to the Army’s Chief of Ordnance, Major General John H. Hinrichs. Work on the project commenced at Picatinny Arsenal in New Jersey in January 1958.

While Ordnance officials explored as many as twenty potential delivery systems, including guided missiles, standard artillery, and mortars, the Army settled on a recoilless rifle system, which offered the simplest and lightest option. Additional work on what was now referred to as the Battle Group Atomic Delivery System (BGADS) was conducted at Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois; Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania; Watervliet Arsenal, New York; Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland; Lake City Arsenal, Missouri; and Watertown Arsenal, Massachusetts. Army Chief of Staff General Maxwell D. Taylor considered development of the BGADS a high priority and a key component of the Army’s new “pentomic” divisions, a reorganization of the Army’s force structure believed to improve the Army’s ability to fight on the nuclear battlefield.

In August 1958, the Army officially began to refer to the BGADS as the Davy Crocket, after the American folk hero, frontiersman, and politician who died at the Alamo in 1836, though the name had been used months earlier. In November 1958, the Ordnance Corps delivered the first prototype Davy Crockett recoilless rifle tube at Picatinny Arsenal. After several years of development and testing at various Army arsenals, Forts Greeley and Wainwright in Alaska, and the Yuma Test Station in Arizona, the M28/M29 Davy Crockett entered service in May 1961.

The Davy Crockett was produced in two variants: the “light” M28 120mm recoilless rifle and the “heavy” M29 155mm recoilless rifle. The M28 had a range of approximately 1.25 miles (2 kilometers), while the larger M29 could launch a projectile out to 2.5 miles (4 kilometers). Both variants fire the 76-pound M388 atomic projectile, which had a diameter of eleven inches and a length of thirty-one inches. After firing, four fins on the round’s tail popped out to stabilize it in flight. Due to its oblong shape, some soldiers referred to the projectile as the “atomic watermelon.” The M388 carried the W54 warhead, the smallest nuclear weapon deployed by U.S. armed forces. The W54 weighed fifty-one pounds and had an explosive yield of .01-.02 kilotons of TNT (the equivalent of approximately 10-20 tons). The same warhead was also used in the Special Atomic Demolition Munition and the Air Force’s AIM-26 Falcon air-to-air missile.

The Davy Crockett was operated by a three-man crew and mounted on an M38 or M151 jeep. Both variants could be launched from jeeps, but they could also be launched from a tripod placed on the ground. The M28 launcher weighed 185 pounds. The larger M29, weighing in at 440 pounds, was often carried by an M113 armored personnel carrier (APC), but it was fired only from a tripod mounted on the ground near the vehicle, not from the APC itself.

After firing a “spotting” round from either a 20 mm (M28) or a 37 mm (M29) gun attached to the Davy Crockett launch tube to determine the proper distance and angle for the target, the crew inserted the propellant charge down the muzzle, followed by a metal piston. It then loaded the sub-caliber spigot on the rear of the M388 projectile into the barrel of the launcher like a rifle grenade. A switch on the warhead allowed the crew to select the height of detonation. Upon firing, the M388 left the launcher with a great bang and large cloud of white smoke, reaching a speed of 100 miles per hour. Since the launch tube was smoothbore, accuracy was always a problem. Nevertheless, what the Davy Crockett lacked in accuracy it made up for in power, although the initial radiation created by the detonation of the W54 warhead would be as lethal to the enemy, if not more so, than the heat and blast effects. Since the warhead also posed a threat to the crew firing it, the Army recommended that soldiers manning the Davy Crockett select firing positions in sheltered locations, such as the rear slope of a hill. Soldiers were also encouraged to keep their heads down to protect themselves from the warhead’s detonation.

The Army began deploying the first M28/M29 systems in 1961 to Europe to equip Davy Crockett sections within Seventh Army’s armor and infantry battalions, in particular those defending the Fulda Gap in West Germany, the expected invasion route of Warsaw Pact forces advancing west. Davy Crockett units were also deployed to Guam, Hawaii, Okinawa, and South Korea. Eventually the lighter M28 was phased out and replaced by the M29 in all Davy Crockett-equipped units.

The Army began deploying the first M28/M29 systems in 1961 to Europe to equip Davy Crockett sections within Seventh Army’s armor and infantry battalions, in particular those defending the Fulda Gap in West Germany, the expected invasion route of Warsaw Pact forces advancing west. Davy Crockett units were also deployed to Guam, Hawaii, Okinawa, and South Korea. Eventually the lighter M28 was phased out and replaced by the M29 in all Davy Crockett-equipped units.

While the Army conducted dozens of live-fire tests of the Davy Crockett with training rounds, only two live M388 atomic projectiles were detonated. The first occurred on 7 July 1962 at the Nevada Test Site when an M388 suspended in the air by wires was detonated a few feet off the ground in the Little Feller II weapons shot. Ten days later, in the Little Feller I shot, an Army crew fired a live M388 from an M29 launcher. The warhead detonated at a height of approximately twenty feet and at a distance of 1.7 miles from the launcher. The test was conducted in conjunction with Operation IVY FLATS, a series of maneuvers to train soldiers in nuclear battlefield conditions. Among the VIPs in attendance were Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and presidential military advisor General Maxwell D. Taylor, who made the development of the Davy Crockett a priority when he served as Army Chief of Staff. Little Feller I also marked the last above-ground nuclear test at the Nevada Test Range.

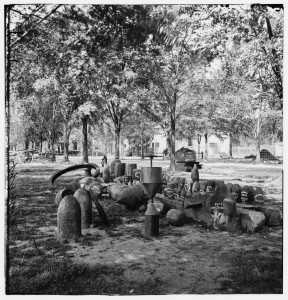

As with other nuclear weapons of the Cold War era, the Davy Crockett was, fortunately, never used in combat, and its service with the Army was relatively brief. By 1967, the Army began withdrawing the Davy Crockett from Europe, and by 1971, it was retired from service. Today, a number of Davy Crockett systems can be found in several museums throughout the United States, including the Don F. Pratt Museum at Fort Campbell, Kentucky; the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albuquerque, New Mexico; and the West Point Museum at West Point, New York.