Written By: MAJ Glenn T. Williams, AUS-Ret.

In 1778 the Continental Congress authorized funds and instructed General George Washington to send an expedition of the Continental Army into Iroquois country to “chastise,” or punish, “those of the Six Nations that were hostile to the United Stated.” For more than two years, four of the Iroquois Confederacy’s Six Nations, specifically the Cayuga, Onondaga, Mohawk and Seneca, along with many of the tribes they considered their “dependents” and allies, had “taken up the hatchet” in the king’s favor.

Although led by their own war chiefs, the war parties were often accompanied by officers and rangers of the British Indian Department, who coordinated their efforts with the British military. Other Crown forces were also operating against American settlements. One was a corps of Loyalist volunteers and Mohawk warriors commanded by Captain Joseph Brant, or Thayendanegea, a Mohawk leading warrior and officer of the British Indian Department. Another was Butler’s Rangers, a corps of Provincial regular light infantry raised specifically to “cooperate” with the allied warriors and fight according to the Indian “mode” of warfare. It was commanded by long-time Indian Department officer John Butler. Butler served concurrently as the Deputy Superintendent for the Six Nations with the Indian Department rank of lieutenant colonel, while at the same time holding a major’s commission in Provincial service as the commander of his ranger battalion. Together they these forces conducted a campaign that terrorized American frontier settlements of New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

These attacks had several objectives. First, they could divert the attention of Continental forces from the movements of their regular field armies. Second, keeping the backcountry alarmed would interfere with the recruitment of potential volunteers from those districts, and hinder the ability of the militia to reinforce the hard-pressed Continentals. This strategy also constituted a form of economic warfare. By attacking productive agricultural communities, laying fields to waste and destroying harvested crops and livestock before they were taken to market could prove destructive to American commerce. The British could also interfere with the American supply system by reducing the availability of provisions that could be purchased to stock military supply magazines, and force state governments to draw on the provisions already stored in them for the relief and subsistence of suffering inhabitants. The plunder taken from the targeted American farms also presented British irregulars and their allied Indian war parties a source of supply when donations from “friends of the king” were insufficient. There was also an element of psychological warfare in the British plans. Under the threat of attack and devastation lest they swear allegiance to the king, the war on the frontier could weaken support for the cause of independence. These “depredations” reached a peak in 1778, especially with the particularly brutal Wyoming and Cherry Valley Massacres, and all intelligence indicated the raids would continue into 1779. Answering calls by the governors and congressional delegates from those states most affected, the Continental Army prepared to take the offensive.

Washington began developing a plan for a coordinated campaign to “scourge the Indians properly.” He envisioned an operation “at a season when their Corn is about half grown,” and proposed a two-pronged attack, the main effort advancing up the Susquehanna from the Wyoming Valley, and a supporting wing advancing from the Mohawk. Both would be supported by a third expedition advancing up the Allegheny River and into Iroquois country from Fort Pitt as a diversion. In his planning guidance, Washington specified the “only object should be that of driving off the Indians and destroying their Grain.” Once accomplished, the expedition would return to the Main Army whether or not a major engagement was fought.

was a Mohawk leader and a

British Indian Department officer

with the rank of captain. He

acquired a reputation for military

skill and bravery during fighting

on the American frontier. (Joseph

Brant, by George Romney,

National Gallery of Canada)

This was economic warfare in retaliation, aimed at the enemy’s ability to wage war, not necessarily the destruction of his forces on the battlefield. Successful execution would also force the hostile tribes to choose between two equally unpleasant consequences. They could either change sides and become allies of the Americans, or become even more dependent on the Crown in return for their continued loyalty. Choosing the former could secure the American frontier in return for the Continental Congress and state governments providing the Indians subsistence. Choosing the latter would further tax the already strained British logistics system in Canada. Either outcome was more beneficial to the American cause than doing nothing for the backcountry settlements as the main American army faced the entrenched British forces around New York City.[1] Furthermore, an operation in Indian country would at least offer some relief to the embattled frontier settlements for the season. On February 25, Congress formally authorized Washington to plan and execute an Indian expedition in 1779.[2]

As he prepared to take command of the “Western Army,” Maj. Gen. John Sullivan studied the mission and the available intelligence on the enemy and terrain over which he and his men would march and fight. Troops and stores were soon put in motion to their respective assembly areas at Wyoming, Canajoharie and Fort Pitt. As the expedition’s start was repeatedly delayed by supply problems, General Washington wrote a very frank letter detailing his instructions to Sullivan. The “immediate objects” of the operation was “the total destruction and devastation” of the settlements of the Six Nations. It was essential that their crops then in cultivation were ruined, and the Indians be prevented from planting more that growing season. It was also important to “capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible” to use for prisoner exchange and to ensure that any negotiations were conducted in good faith.[3]

Sullivan then decided that instead of conducting a supporting attack, the 1,500 troops of Brig. Gen. James Clinton’s New York Continental brigade would join his 3,000-man division on the Susquehanna, and march together by the “most practicable route into the heart of the Indian Settlements.” In doing so, Washington recommended that Sullivan establish at least one post in enemy territory from which his forces could operate. He was then to send detachments “to lay waste all the settlements around with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner,” by which “the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed.”[4]

Although Sullivan was confident of success, he held no illusions that the campaign he was to lead would be an easy one. Enemy forces were estimated at 2,000 hostile warriors and several hundred Provincial soldiers. He described the enemy warriors his expedition would face as “perfectly acquainted with the country, capable of seizing every advantage which the ground can possible afford, inured to war from their youth, and from their manner of living, capable of enduring every kind of fatigue.” Sullivan expressed a grudging respect when he wrote they “are no despicable enemy,” and realized that a two to one numerical advantage was no guarantee of success. Although confident, he was not overly so. He knew that the warriors of the Six Nations, even “when opposed to three thousand troops,” were still formidable.[5]

In order to prevent defeat by such irregular forces on ground of their own choosing, Washington cautioned Sullivan that his force should seek “to make rather than receive attacks, attended with as much impetuosity, shouting and noise as possible.” The men should, “whenever they have an opportunity, to rush on with the war-whoop and fixed bayonet.” Washington believed “Nothing will disconcert and terrify the Indians more” than an aggressive attack carried out with audacity. If after the destruction of their settlements was complete, and the Indians showed a “disposition for peace,” Sullivan was instructed to encourage it on the condition that they provided evidence of their sincerity. One way the Indians could prove their sincerity was delivering into American custody some of those who instigated or led the attacks against the frontier settlements, like “the most mischievous of Tories, Butler and Brant, or any others in their power.” Another sign of friendship would be the capture of Fort Niagara from the British.[6]

In the weeks while the army waited for supplies, Sullivan’s troops trained in the woods, defiles, swamps and hills around the Wyoming Valley. And Clinton’s in the area around Lake Otsego. They practiced and rehearsed the pre-planned actions they would take to immediately respond to enemy contact with Indian warriors and British irregulars. Sullivan’s army was prepared to deny the enemy their greatest advantage when fighting in the forest, the element of surprise. When Clinton’s brigade joined with Sullivan’s wing at Tioga Point, the march order designed to meet the tactical considerations. The men of Maj. James Parr’s Rifle Corps dispersed “considerably in front” with orders to “reconnoiter mountains, defiles and other suspicious places” ahead to prevent the enemy from launching a surprise attack or ambush. The two musket battalions of Brig. Gen. Edward Hand’s provisional brigade, detailed as the expedition’s “Light Corps,” formed in six columns, each separated by 2 to 300 yards and proceeded by companies of light infantry. The artillery park was next in the order of march, with four light 3-pounder bronze guns, two 3-pounder iron guns, two 5½ – inch howitzers and a cohorn mortar, nine pieces in all. The rest of the artillery train, consisting of a traveling forge and three ammunition wagons, followed the guns.[7]

To facilitate their deployment into line of battle regardless of where the enemy struck, the main body moved in a “hollow square” formation, with Brig. Gen. Enoch Poor’s New Hampshire brigade marching in column of platoons, aligned with the right division of Hand’s brigade, and Brig. Gen. William Maxwell’s New Jersey brigade arrayed in the same manner on the left. Each brigade detailed about 200 men from its regiments to provide flankers, or security on its respective side along the line of march. Clinton’s New York brigade moved in six columns, mirroring the deployment of Hand’s brigade, at the back of the square, with one of its regiments detailed to provide the rear guard. Inside the square, the army’s 1,200 packhorses marched in two columns along the center, while the drovers herded the 800 head of beef cattle between the pack train in the center and brigade columns on the flanks of the square.[8]

by the regulations of 1779. (The

American Soldier, 1781, by H. Charles McBarron, Army Art Collection)

Meanwhile, Maj. Butler and his Provincial Rangers, a detachment of British regulars, and Capt. Brant with his corps of Loyalist Volunteers and Mohawks had combined with a force of all the warriors the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga and Delaware chiefs could gather, just under 1,000 men in all, near a Delaware village called Newtown. Expecting the American army to advance by marching in column either along the banks of the Chemung River or through the woods on an Indian trail, Butler and the chiefs chose their ground well. Facing the direction of the American approach, there was a ridge of about one half mile in length that dominated a plain of land that bordered the river to the right. If the Americans came that way, the position afforded a relatively small force the ability to subject the attackers to a withering fire. A steep mountain stood on the left, parallel to the ridge, where warriors fighting Indian style could punish an American force advancing through the woods. From between the hill and ridge, the trail from Chemung emerged from a swamp into a large open area before it crossed a steep defile with cut by a large creek. It was a perfect site for an ambuscade.

A relatively small force, like that at Butler’s command, could surprise an unsuspecting foe as it emerged into the clearing by opening fire from concealed positions, and hold the Americans in front while Indian warriors swept down around their flanks from the foothills, and assaulted through the woods. If the Indians gained the rear of Sullivan’s army, they could cause great confusion, possibly stampede the cattle, and inflict casualties disproportional to their numbers. Maybe the invading Americans would be so disheartened that they would abandon their planned invasion. It could be like the battle of Oriskany all over again. At the very least, a few companies massing their musket fire could get off one or two volleys without risking many casualties before they yielded the field to the much larger enemy army. They could at least buy time for Maj. Gen. Frederick Haldimand, the Royal Governor of Quebec and commander in chief of British forces in Canada, and the allied tribes to send reinforcements before the Americans reached the principal Indian towns. As they waited, Butler’s men disassembled the buildings near their line for their wood, chopped trees and “threw up some Logs one upon the other by way of a Breastwork,” and masterfully concealed it from enemy view by bushes and other foliage.[9]

The semicircular disposition offered Butler and the Indians the advantage of interior lines, where reinforcements could be sent to meet a threat from any part of the line not heavily engaged. Most of the Iroquois warriors were posted to the foot of the mountain. Capt. John McDonnell with sixty of Butler’s Rangers, Capt. Brant with thirty Loyalists and Mohawks, and a war party of thirty Cayuga under their own chief took position on the ridge. The detachment from the 8th Regiment of Foot, the rest of Butler’s Rangers and the remaining Indians manned the center at the breastwork overlooking the creek. In order to give his attention to the Indians and coordinate the combined effort, Maj. Butler placed his son, Capt. Walter Butler, in command of the rangers. When scouts reported that the Americans camped a few miles downstream, Butler and the chiefs felt their men were ready.[10]

As the Americans marched along the Indian trail toward Newtown on 29 August, the leading elements began engaging Indian warriors deployed as skirmishers in the woods. The further the American riflemen and light infantrymen advanced, the bolder the enemy skirmishers became, although they did not stand and fight, but ran into the woods before the riflemen’s advance. After entering some marshy ground, which “seemed well calculated for forming ambuscades,” the light troops advanced with precaution as more Indian warriors fired and retreated. Maj. Parr suggested to Gen. Hand that the situation was too dangerous to proceed without further reconnaissance, lest the warriors lure them into a trap. The major ordered one of his men to climb up a tree in order to “make discoveries” of the enemy up ahead. From that vantage, after some time, “he discovered the movements of several Indians, which were rendered conspicuous by the quantity of paint on them.” The rifleman described the enemy as “laying behind an extensive breastwork, which extended at least half a mile, and most artfully concealed with green boughs and trees.” As the Americans viewed it, the line was situated on high ground, with the left flank secured by a mountain and the right by the river. To assault the works directly, the Americans had to cross marshy ground, ford a difficult stream, and advance uphill through a cleared and open field 100 yards wide.[11]

Immediately after Parr informed him of the enemy disposition, Gen. Hand advanced the Light Corps under concealment to within 300 yards of the enemy’s breastworks, and formed a line of battle. The riflemen advanced under cover as far as the creek and “lay under the bank” within 100 yards of the enemy. Gen. Sullivan arrived, and sent for the rest of his subordinate commanders for a council of war while waiting for the army to move up.[12]

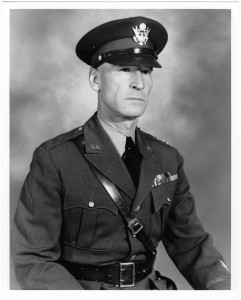

several Revolutionary War battles,

was chosen by GEN Washington

to lead the campaign against the

Iroquois. (National Park Service)

The enemy’s fortifications “were very extensive, tho’ [sic] not impregnable.” Because the Americans did not want to merely drive the Tories and Indians out of their defenses, Sullivan presented a plan to turn their flank in order to “bring them to a fair and open action.” The Rifle Corps and light infantry would continue to “amuse” the enemy, and keep his attention fixed in front. Col. Matthias Ogden, with the 1st New Jersey Regiment and the rest of the left flanking division, would form on the Light Corps’ left flank, and if the opportunity presented itself, assault the ridge and turn the enemy’s right. Col. Thomas Proctor was to move the artillery, six 3-pounders, two 5½-inch howitzers and cohorn, in front and centered on the regiments of the Light Corps, immediately opposite the enemy breastwork, to support by fire. The guns would remain concealed until all was ready. Gen. Maxwell’s brigade, minus the left flanking division, was to “remain some distance to the rear” as the corps de reserve. The brigades of Poor and Clinton, along with the right flanking division, were to gain the enemy’s left flank and rear, and cut off their retreat along the road through Newtown toward Catherine’s Town. For the plan to succeed with the desired effect, it was imperative that the units making the flank attack were in position to take the enemy in the rear when the artillery cannonade commenced. The Rifle Corps and light infantry would then advance on the breastwork.[13]

was the only major action of the 1779 Iroquois Campaign. (Chemung County Historical

Society)

At about 1 o’clock, the diversion began. Tory Maj. Butler recalled, “A few of the Enemy made their appearance at the skirt of the wood to our Front.” The riflemen then went into action. According to Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, of the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment of the Light Corps, “A heavy fire ensued between the rifle corps on the enemy, but little damage was done.” At the same time, the artillery filed off to the right, and was “carried to an advantageous piece of ground” about a quarter mile from the Tory breastwork. Generals Poor and Clinton then ordered their brigades to “march by column from the right of regiment by files.” The troops passed through a very thick swamp overgrown with bushes. For nearly a mile, the “Columns found great difficulty in keeping their order.” But by Poor’s “great Prudence & good conduct,” however, experienced officers like Lt. Col. Henry Dearborn remarked that the brigade “proceeded in much better order than I expected we possibly could have done.” After negotiating the swamp, the columns inclined to the left, and crossed the creek, which ran in front of the enemy’s breastwork farther downstream. As they did so, the soldiers noticed about twenty unoccupied buildings, which curiously had no land cleared nearby for cultivation. Some of the men assumed these were to be used for magazines to supply raiding parties heading for the frontier settlements. Once across, the troops began to ascend the mountain that defined the enemy’s left.[14]

After the American riflemen had “amused” his troops and warriors facing them across the open field for about two hours, the Tory commander suspected that the Americans were not taking the bait he had dangled in front of them. Unlike the militia he had faced at Oriskany or Wyoming, these regulars were not lured into the defile where his men could blaze away at them from behind their breastwork. When it became apparent that the Americans were probably deploying to bring their overwhelming numbers to bear, Butler considered a retreat. While the Rifle Corps occupied their attention to the front, however, the Indians were reluctant to leave their fortification. Brant and the Cayuga chief left their position on the right to meet with Butler, and recommended withdraw before they became decisively engaged in a losing battle.[15]

At about 3:00 PM, the American artillery was ordered to advance to the high ground on the near side of the defile, about 200 yards from the enemy position. The guns, howitzers and cohorn opened fire on the breastworks as “the rifle and light corps… prepared to advance and charge.” The storm of round and grape shot soon “obliged” the defenders to leave their log fortification. When howitzer and cohorn shells began bursting above and behind them, many of the Indians believed the Americans had surrounded them with artillery. Many of the warriors were “So startled & confounded,” that a “great part of them run off” in panic. Butler led his rangers and a number of the Indians toward the hill that marked the left of their line in order to retreat.[16]

The swamp and thickets had delayed the progress of Poor’s and Clinton’s brigades, so that they were not yet in position when they heard the cannonade begin. After ascending halfway up the hill, the Continentals were “saluted by a brisk fire” and war whoops from a body of Indians posted to keep them from turning the flank of the breastwork. As the riflemen of the flank division kept up a “scattering fire,” the rest of Poor’s brigade quickly formed the line of battle. Though much fatigued by the difficult march and climb under the burden of heavy packs in the oppressive heat, the troops pressed up the hill. With their lines dressed and bayonets fixed, the disciplined Continentals advanced rapidly in the face of enemy fire, and without returning a shot, drove the enemy “from tree to tree” before them. On reaching the summit, the command was given, and Poor’s soldiers leveled their muskets and fired a full volley that broke the resistance of the Indians to their front, and sent them flying. Clinton’s brigade, following Poor’s up the hill by a quarter mile, “pushed up with such ardor” that a number of soldiers fainted from heat exhaustion. As they closed on the crest, Clinton’s brigade extended to the right and endeavored to block the enemy’s retreat through the defile along the river.[17]

When they heard the musketry of Poor’s battle on the hill, Maj. Butler and the rangers and redcoats realized the Americans had gained the high ground on their flank, and threatened to surround them. At the same moment, Hand’s Light Corps attacked and swarmed over the breastworks as the last of the British, Tories and Indians abandoned them in flight. In desperation, the remnants of Butler’s command turned west. Nearly surrounded, the warriors, rangers and redcoats made their escape as best they could, carrying many of their dead and wounded. Some kept along the hill, skirmishing with the pursuing American light infantry for over a mile. Others crossed the Chemung River or took to canoes to avoid capture. Most rangers headed for a village about five miles away where Butler had told them to rendezvous. Many warriors, however, crossed the mountain in an attempt to return to their homes.[18]

Meanwhile on the hill, although most regiments of Poor’s brigade remained on line, Lt. Col. George Reid’s 2nd New Hampshire “was more severely attacked,” and prevented from advancing as far as the rest. Lt. Col. Henry Dearborn, commanding the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment on Reid’s right, saw what was happening. Reid’s unit had become separated from the rest of the brigade by a distance of “more than a gun shot.” Dearborn therefore “thought it proper” to “reverse the front” of his unit and go to Reid’s assistance. On the enemy side, a large body of warriors saw the opportunity to attack the American rear by going around the left of Poor’s brigade, but Reid’s regiment stood in their way. They clashed on the slope of the hill, and the warriors were in the process of surrounding the Continentals. Reid “was reduced to the necessity” of ordering either a retreat back down or a desperate bayonet charge up the mountain. He chose the latter, and had no sooner given the order to execute the move when Dearborn’s regiment arrived and fired a full volley that broke the Indian attack. The enemy now left the scene of action “in great precipitation & confusion,” leaving nine dead warriors on the field.[19]

as Secretary of War during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson

and was the Army’s senior officer

during the War of 1812. (Henry Dearborn, by Walter M. Brackett, Army Art Collection)

Soldiers of Hand’s corps pursued the enemy beyond the breastwork and along the mountain until they made contact with the flanking brigades. The rifle and light infantry companies continued the pursuit for another mile or so before returning to join the rest of the army in Newtown at about 6:00 PM, where they encamped on the same ground the enemy had previously occupied. Three Americans were killed and thirty had been wounded, one of them mortally.

The rout of the enemy had been complete. The enemy’s former positions were littered with brass kettles, packs, blankets and other articles dropped in their haste to carry off their dead and wounded in the escape. Some of Poor’s men scalped the Indian corpses, as others searched for lurking warriors who could still be in the area. Two prisoners, “a white and a Negro,” were taken. The white Tory had feigned death until an officer noticed that there were no wounds on his body. After being struck with the side of a sword and ordered to get up, the man pleaded for mercy. The black prisoner was taken by Hand’s light infantry after he became “separated from his company” during the retreat. Butler reported the loss of five dead and three wounded rangers, and five dead and nine wounded Indians.[20]

Newtown was the only significant engagement of the 1779 Indian Expedition. The British had relied on their rangers and Indian allies to conduct irregular operations in the forest to retard or halt the Americans, but they proved incapable of withstanding the onslaught. In a message to Lt. Col. Mason Bolton of the British garrison at Fort Niagara, Maj. Butler blamed the loss on “some officious Fellow” among the Indian chiefs repositioning men on the flank, and the poor turnout of Iroquois and Delaware warriors. Notwithstanding, he admitted to Bolton that the American army “moved with the greatest caution & regularity and are more formidable than you seem to apprehend.” [21]

The major warned of the serious consequences that would follow if his rangers and Indian warriors were unable to stop them. If there was not “speedily a large Reinforcement,” Butler was certain that after the Indians’ villages and corn were destroyed, the refugees would flock to Fort Niagara, where they would consume large quantities of provisions and be in need clothing and shelter that was already in short supply for the king’s forces.[22] The Tory rangers and their Indian allies, however, were never able to mount a credible defense of Iroquois country.

The American invasion resulted in the destruction of forty Indian towns and agricultural fields yielding some 160,000 bushels of corn and other vegetables before returning to the main army. Sullivan’s army had “chastised” the forces of the Six Nations that were hostile to the United States for taking the side of the British, and forever ended the Iroquois Confederacy’s military dominance over other Indian nations. Although the hostile nations remained allies, the British supply system was indeed strained to support them in their distress. When the British ceded their land to the victorious United States by the Treaty of Paris that ended the war in 1783, their Indian allies paid the consequences for the alliance they made with the Crown in 1777.

[1] Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene to Gen. George Washington, letter dated Philadelphia, January 5, 1779, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, (Greene Papers ), Showman, Richard K., ed., Chapel Hill, NC:, Volume III, 145.

[2] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789. Edited from the original records in the Library of Congress, (hereafter JCC), 34 volumes, Ford, Worthington C. ed. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), Volume 13, 251.

[3] Gen. George Washington to Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, letters dated Head Quarters, Middlebrook, May 28 and 31, 1779, The Writings of George Washington from the original manuscript sources 1745-1799Writings of Washington (hereafter Writings of Washington), Fitzpatrick, John C., ed., (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1934), Volume 15, 171-173.

[4] Gen. George Washington to Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, letter dated Head Quarters, Middlebrook, May 28 and 31, 1779, Writings of Washington, Volume 15, 171-173, 189-193.

[5] Maj. Gen. John Sullivan to Gen. George Washington, letters dated Mill Stone, April 15 and 16, 1779, The Letters and Papers of Major General John Sullivan, Continental Army (hereafter John Sullivan Papers), Hammond, Otis G., ed., (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Historical Society, 1939), Volume 3, 1-5, and 5-9.

[6] Gen. George Washington to Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, letter dated Head Quarters, Middlebrook, May 28 and 31, 1779, Writings of Washington, Volume 15, 171-173, 189-193.

[7] Parker, Robert. “Journal of Lieutenant Robert Parker of the Second Continental Artillery, 1779.” Bard, Thomas R. ed., Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, volume 27, (Harrisburg, PA: 1904), 12-25; Maj. Jeremiah Fogg, Journals of the Military Expedition of Major General John Sullivan against the Six Nations of Indians in 1779, (hereafter Journals), Cook, Frederick, ed., (Auburn, NY: Knapp, Peck & Thomson, 1887, reprinted, Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2000), 94; Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, Journals, 154; “Diaries,” Lieut. James Fairlie, Mss, New York State Library.

[8] Fairlie Journal; Journals, Lieut. Erkuries Beatty, 26; Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, 154.

[9] Maj. John Butler to Lt. Col. Mason Bolton, letter dated Shechquago, August 31, 1779, Haldimand, Sir Frederick, Official correspondence and papers, National Archives of Canada, copied courtesy of British Library (formerly British Museum), London, Gen. Sir Frederick Haldimand Manuscripts Collection, (hereafter Haldimand Papers), B 100, 242.

[10] Maj. John Butler to Lt. Col. Mason Bolton, letter dated Shechquago, August 31, 1779, Haldimand Papers, and B 100, 242.

[11] Journals, Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, 155; Maj. John Burrows, 45; Lieut. John Jenkins, 172.

[12] Journals, Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, 155.

[13] Brig. Gen. James Clinton to Gov. George Clinton, letter dated New Town, August 30, 1779, Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York (hereafter Clinton Papers), Hastings, Hugh, ed., Volume 5 (Albany, NY: State Historian, 1899-1914), 224-227; Journals, Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, 155-156.

[14] Ibid; and Journals, Lt. Col. Henry Dearborn, 71; Maj. Jeremiah Fogg, 84.

[15] Maj. John Butler to Lt. Col. Mason Bolton, letter dated Shechquago, August 31, 1779.

[16] Parker Journal; Ibid Butler; Journals, Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, 156.

[17] Brig. Gen. James Clinton to Gov. George Clinton, letter dated New Town, August 30, 1779; Journals, Lt. Col. Henry Dearborn, 72; Capt. Daniel Livermore, 186; Maj. James Norris, 231-232.

[18] Maj. John Butler to Lt. Col. Mason Bolton, letter dated Shechquago, August 31, 1779.

[19] Journals, Lt. Col. Henry Dearborn, 72; Capt. Daniel Livermore, 186; Maj. James Norris, 231-232.

[20] Brig. Gen. James Clinton to Gov. George Clinton, letter dated New Town, August 30, 1779; T. Barton to Gov. George Clinton, letter dated Newtown, August 30, 1779, Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, (hereafter Clinton Papers), Hastings, Hugh, ed., (Albany, NY: State Historian,1910) Volume 5, 242; Maj. John Butler to Lt. Col. Mason Bolton, letter dated Shechquago, August 31, 1779; Journals, Lieut. William Barton, 8; Maj. John Burrows, 44; Maj. James Norris, 232.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.