Written By: Paul Herbert

On 28 May 1918, the 28th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. 1st Division attacked a German-held French village called Cantigny some seventy miles north of Paris. This operation marked an important moment in the history of the U.S. Army. A small battle by World War I standards, the Battle of Cantigny was America’s first significant battle, and first offensive, of World War I. It helped wrest the initiative from the German Ludendorff Offensive and bolstered the morale of America’s European allies at a critical moment. On its outcome, in part, rode the “amalgamation” question of whether arriving American doughboys would join an independent American field army or serve as replacements in the French and British armies. It provided lessons and experience that shaped the Americans’ approach to battle for the rest of the war and afterwards. It provided a young George C. Marshall, 1st Division operations officer, his first and only combat experience at the tactical level. Cantigny marked the emergence of the modern, permanently established, combined arms division in the U.S. Army, an organization that remained central to that army for the rest of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Furthermore, it was America’s first commitment in blood to democracy in Western Europe.

Two momentous events in 1917 set the 28th Infantry Regiment on its path from the U.S.-Mexican border in Texas to the poppy-covered fields of Cantigny. Germany’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in February provoked an American declaration of war in April and a promise from President Woodrow Wilson to immediately dispatch “a division” (of which the United States had none) to France. As one of the four infantry regiments selected to comprise the “First Expeditionary Division,” the 28th was among the very first to arrive in France in June 1917 and complete enough training to be ready by the spring of 1918. Meanwhile, in November 1917 Russia’s revolutionary government signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, a separate peace agreement with Germany that allowed the transfer of German divisions west from the Eastern Front. There they were to provide the muscle for a last great offensive to win the war before American power could be brought to bear.

Central to the German offensive was the reorganization and retraining of their assault divisions. The Germans decided to eschew the massive, multi-day artillery preparations followed by waves of attacking infantry that characterized many Great War offensives. These often resulted in horrific casualties for little gain, the consequence of heavy defensive firepower and ground so broken that sustaining the effort was impossible. Instead, the Germans substituted short but intense artillery bombardment followed immediately by infantry squads that carried grenades, light machine guns, and small cannon and sought to bypass resistance and move deep into the enemy’s defenses. Inspired by earlier, decentralized tactics for the defense and practiced at the Battle of Caporetto in Italy in November 1917, the new German doctrine, often attributed to General Oskar von Hutier, gave German General Eric Ludendorff hope of a decisive breakthrough.

While the Germans prepared their offensive, the 1st Division struggled through the final stages of becoming the modern, combined arms organization envisioned by Army planners. Army plans called for a 27,000-soldier division of two infantry brigades of two regiments each; an artillery brigade with two regiments of 75mm guns, one to support each infantry brigade, and a regiment of 155mm howitzers for general support; a regiment of engineers; three machine gun battalions; and significant numbers of supporting troops, including an ammunition train, military police, field signal units, hospitals and ambulance companies, and motorized and horse-drawn transportation units. This organization had been agreed upon between GEN John J. Pershing’s Headquarters, American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), and War Department representatives on the ship carrying the former to France in June 1917. Many of the soldiers of the 1st Division arrived in France as hastily enlisted recruits. Their equipment was issued in France or followed the troops by sea. Officers literally had to teach themselves the rudiments of a new form of warfare as they taught their soldiers.

The 1st Division’s training occurred in four stages between its arrival in June 1917, and its deployment to Cantigny the following April. First, near Gondrecourt, in Lorraine, it learned the basic skills of trench warfare under the supervision of the French 47th Division (Chasseurs Alpin). In October 1917, it began rotating infantry and artillery battalions to the front in the sector of the French 18th Division, between Nancy and Luneville. For six weeks beginning in late November, it conducted large-scale exercises in “open warfare,” that is, coordinated maneuver, fires, and logistical support on ground not scarred by trenches, a skill perceived by Pershing as essential to the eventual pursuit and destruction of the German armies beyond their trenches. Declared ready for service at the front on 7 January 1918, the 1st Division assumed responsibility for its own subsector in the Ansauville Sector of the French XXXII Corps, north of Toul and along the St. Mihiel salient, near Seicheprey, on 5 February 1918.

Service there honed the division’s combat skills. Under the aggressive leadership of MG Robert L. Bullard, the 1st Division kept up an active program of artillery fires and raids across “no man’s land” while completely reorganizing its subsector in depth to account for the new German offensive doctrine. Meanwhile, only four other U.S. divisions were available in France (the 2d, 26th, 32d and 42d), all of them at earlier stages of the same training sequence.

The Germans attacked the British Third and Fifth Armies on 21 March 1918 along a forty-mile front straddling the Somme River, just north of where the British and French armies joined, in an attempt to seize Amiens. That city on the Somme was a critical railway link between the British and French sectors. The Germans believed that capturing Amiens would sever the two armies, causing the British to withdraw north to protect the channel ports, while the French would retreat south to protect Paris. The Germans hoped that this separation would yield opportunities for them to bring the war to an end on their terms. For more than two weeks, the German advance of nearly forty miles, unprecedented since 1914, threatened to succeed and threw the Allies into real crisis.

The German initiative disrupted Pershing’s carefully nurtured plans for an autonomous American sector of the Western Front. Pershing had hoped to bring two and possibly more U.S. divisions alongside the 1st Division in Ansauville to form the I U.S. Corps, a first step toward an American field army. On 25 March, French General-in-Chief Henri Phillippe Pétain requested use of U.S. divisions to replace French divisions in sectors not threatened by the new German offensive. Because U.S. divisions were nearly double the size of their French counterparts, the five American divisions then available in France could release ten French divisions for commitment against the Germans.

Pershing agreed, and later famously offered “all that we have” to stem the crisis, in effect postponing indefinitely his plans to consolidate the American army. The crisis also forced the Allies to establish rudimentary unity of command over the Western Front. Until the Germans struck, the military efforts of the European allies had been loosely coordinated by the Supreme War Council, with the United States participating as an “Associated” but not “Allied” power, while command remained in national channels. On 3 April, the Allies vested in French General Ferdinand Foch overall authority for direction of the Western Front.

Pershing generously repeated his offer of U.S. resources to the new commander.

Finally, the crisis caused the Allies, and especially the British, to press for trans-Atlantic shipping to be used primarily for U.S. infantry and machine gun units, desperately needed everywhere along the front, rather than the full complement of heavy equipment and support units needed to support an American field army. All these developments tended toward “amalgamation,” that is, the use of U.S. troops as replacements for the French and British armies, rather than in a sector of their own as a complete field army. The Europeans had pressed for amalgamation repeatedly, arguing that there was insufficient time to organize and train a complete American field army, and that the most efficient use of fresh American manpower was in their experienced formations.

This was anathema to the Americans. It would place their citizens under foreign command unresponsive to the U.S. government and, as important, it would obscure the American contribution. To bolster his position at the peace table, President Wilson required an independent American field army with an unambiguous role in defeating Germany. Pershing had continuously assured the Allies that the AEF would be ready for full service promptly. The Ludendorff Offensive put these assurances, and the American position, to its supreme test. On 30 March 1918, at the request of General Pétain, the U.S. 1st Division received orders for its relief by the 26th Division in the Ansauville sector and its immediate movement from Toul to Chaumont-en-Vexin, north of Paris, for commitment somewhere near the apex of the German advance.

The move itself was a challenging exercise. While most of the division’s combat units marched from the front to the railhead at Toul, others were still near Gondrecourt and had to be alerted and moved from there. Soldiers and animals (nearly 6,000) filled approximately forty standard French troop trains of fifty cars each for the circuitous ride around Paris and thence to the detraining station at Meru. From there, they marched to their billets in the villages surrounding the division headquarters at Chaumont-en-Vexin, designated in advance by the French Fifth Army. The division’s motorized elements made the trip by road. The division closed into its new location by 9 April.

Over the next few weeks, the division’s readiness for whatever lay ahead was closely scrutinized from very different perspectives. For the first week after its arrival, it conducted yet more exercises in “open warfare.” Pershing perceived that the German attack had ruptured the front and reached the less entrenched regions deep in the Allied rear areas. The 1st Division thus might meet the enemy on “open” ground as a first test of his “open warfare” theories. The French, on the other hand, were just as interested in the division’s defensive capability. On 9 April, the day the 1st Division arrived, the Germans temporarily halted their offensive against Amiens and struck farther north, near Lys, in the second of their five great offensives, this one designed to draw off British reserves and make a resumption of the attack on Amiens possible. The French, therefore, had a momentary opportunity to bolster their defenses along the south face of the Amiens salient.

While the Americans were intent on demonstrating the 1st Divison’s prowess as a combat unit, the French were intent on learning whether they could trust this relatively raw formation of foreigners. So important was this first American commitment to the battle at hand that Pershing himself came to address the division’s 900 officers on April 16: “…you will represent the mightiest nation engaged,” he told them. “Our future part in this conflict depends on your action.” As if to underscore the point, on 20 April, a German raid on the 26th Division back at Seicheprey met a feeble American response, causing the French corps commander to come personally to the U.S. brigade headquarters to control the fight. The reputation of the American army now rested entirely on the 1st Division’s upcoming performance.

On 24 April, the Germans renewed their attack on Amiens but were halted by the French the next day. That same day, the 1st Division arrived at the apex of the German salient, just west of Cantigny, relieving the French 45th and 162d Divisions and assuming command of the sector on 27 April. In the event of attack, Bullard ordered, “each element will fight on the spot without retiring. Machine guns will be fought until put out of action. All groups will fight to a finish.” Despite warming spring weather and early poppies, the Cantigny sector was not inviting. The French had been there for only about three weeks and had not constructed trenches, shelters, or wire entanglements. The debris of battle, including human and animal remains, was pervasive. German artillery, accurately directed from high ground and balloons, was active throughout the sector.

Casualties accrued immediately. Troops of the 1st Brigade (16th and 18th Infantry Regiments) moved into the 4.5-kilometer sector first, and had to scrape shell holes and foxholes into a feebly connected first “parallel” using pack shovels and bayonets. German soldiers of the 30th Reserve Division glowered over the sector from the ruined village of Cantigny, in a salient on dominant ground in the center. On the night of 3 May, the Germans bombarded the 18th Infantry intermediate positions in the village of Villers-Tournelle opposite Cantigny with over 10,000 mustard gas shells, inflicting over 800 casualties and forcing the near total evacuation of the position. On 5 May 1918, command of the 1st Division passed from the French VI Corps to the French X Corps under Major General Charles A. Vandenberg, whose contingency plans for a corps offensive dominated the next ten days.

When the operation was postponed, Bullard and Vandenberg convinced French First Army commander General Marie Eugene Debeney and GEN Pershing that a smaller attack by the 1st Division to eliminate the German salient at Cantigny would succeed and have “great moral effect…in particular, to confirm the confidence of the staff of the 1st [Infantry Division]…” On 15 May, Debeney gave his approval and set the day of attack (“Day J”) as May 25. Meanwhile, the 2d Brigade of the 1st Division, with its 26th and 28th Infantry Regiments, relieved the 1st Brigade at the front. The envisioned attack was “analogous to a powerful raid” and included a single regiment as the attacking force. The purpose was limited to securing Cantigny and the central portion of the Cantigny plateau, an advantageous position that yielded excellent observation to whichever side held it.

The X Corps attack order posed to Americans for the first time in combat all of the challenges of twentieth century combined arms warfare in an operation that could not fail. Borrowing heavily from the plan for the cancelled corps operation, 1st Division Field Order No. 18, dated 20 May 1918, crafted in the main by 1st Division G-3 LTC George C. Marshall, is a remarkable document, more similar in form and content to all subsequent American field or operation orders than to anything that preceded it.

The scheme of maneuver was simple enough. To seize the Cantigny plateau, the division would attack with a single regiment, its three battalions attacking abreast, each in its own zone. The center battalion would be reinforced by a group of twelve French Schneider tanks and would have the primary task of clearing the main German position in the village of Cantigny itself and advancing to an “objective line” some distance beyond the village.

The battalion to the north would protect the left flank of the main attack and seize the objective line to tie in with the French 152d Division further to the left (north). The battalion to the south would clear the southern edge of the village, including a steep escarpment on its southern face, before moving to the objective line in sector to prevent German counterattack from the southeast. The attack would depend on surprise and weight of artillery. Timed to occur near daybreak, it was to be preceded by only an hour of intense preparatory artillery fires before a rolling barrage and the tanks led the assaulting infantry across no man’s land. The infantry was to signal their occupation of the objective line within forty-five minutes of H-hour and prepare immediately for German counterattack.

Artillery would make the infantry advance possible. The French added eighty-four 75mm guns, twelve 155mm guns, and many mortars that more than doubled the throw weight of the First Division’s two regiments (6th and 7th) of 75mm guns, one regiment (5th) of 155mm howitzers, and the 1st Trench Mortar Battery. 1st Artillery Brigade commander, BG Charles P. Summerall, greatly assisted by French Colonel Count Adalbert de Chambrun as a liaison, planned the fires. Slow, methodical, destructive fire, calibrated to avoid revealing the upcoming attack, would be directed against German defenses near Cantigny and enemy batteries for several days while the French artillery moved by night into camouflaged firing positions. The night before the attack, several concentrations were planned on probable enemy positions, including fifty rounds of gas shells from each of Group Parker’s six batteries of 75mm guns, to be fired at the Bois de Framicourt just east of Cantigny. Two hours before the attack, the artillery would fire at targets for registration purposes and to neutralize German artillery.

The intense preparation would begin one hour before the attack, reaching its full crescendo only three minutes before H-hour. In that time, fires would seek out German targets, form a protective “box” around the attack area, and provide smoke to conceal the approach of the tanks to the line of departure. The rolling barrage would begin at the line of departure three minutes before H-hour and then lead the tank-infantry assault at a pace of 100 meters every two minutes. As the barrage and assault advanced, heavier guns would concentrate on enemy batteries and terrain likely to be used in any German counterattack.

With the scheme of maneuver and artillery plan of employment at its heart, the order then addressed all of the technology that had become available only a year before.

Machine guns, 37mm guns, and Stokes mortars would be added to the infantry battalions, especially to overcome enemy machine guns, and engineer sappers and French flamethrower teams would accompany them. Machine gun batteries would supplement the artillery with barrage fires. Tanks were to assault with the infantry. “Aeroplanes” (having already provided invaluable aerial photographs in near real time) and balloons would aid command and control. The prodigious supplies needed by this form of industrial warfare would be stockpiled forward (more than 128,000 rounds of 75mm ammunition alone) while military police planned to regulate foot, horse, and motor traffic.

A scheme of medical evacuation provided that the wounded be dispatched by pre-positioned motor ambulances to field hospitals designated by type of casualty. Gassed cases were to go to Field Hospital No. 13 at Vendeuil. Perhaps not surprisingly, the order contained schedules and execution matrices that, in modern jargon, would help synchronize the complex operation about to unfold. A synchronized operation among disparate elements required good communications and a common sense of time. For common time, a division memorandum on 27 May dictated that, beginning at noon, watches synchronized to the time at headquarters would be delivered to subordinate commanders who in turn would synchronize and distribute watches within their commands.

Communications were addressed in Annex 9, Plan of Liaison, and other scattered paragraphs. Principal reliance within the division and the artillery commands was on field telephones; an extensive plan dictated two “axes” or trunk lines and two “centrals” or switches, with lateral and subordinate lines. Centrals (Duluth, Minneapolis, Fargo, etc.) were generally co-located with important posts of command. Both axes were to be paralleled with division runners, and unit runners were to parallel their lines. Runner posts were to be no more than 500 meters apart and all messages were to be carefully recorded at each post. Further supplementing this system were optics (lights, rockets, and flares); earth telegraphy (or T.P.S. for telegraphie par sol, involving electrical induction between iron poles driven into the ground); radio; panels and pyrotechnics; and pigeons. Two of the latter were allocated to the attacking regimental commander and each of his battalions. A signal sergeant manned the dovecote and had a direct telephone line to division headquarters.

Runners were also to solve the particular problem of tank-infantry coordination. Two “American runners who speak French” were to be allocated to the center infantry battalion headquarters and each of its companies and likewise to the tank group commander and each of his “batteries” of four tanks. These runners were to be detached to the French tank group immediately to familiarize themselves with their counterparts. During the attack, two dismounted French soldiers were to walk behind each tank to coordinate with American infantry.

Aviation posed a special problem. The ten infantry liaison airplanes of Spad 42 assigned to the 1st Division were to fly a red flag from their left wings. A handbill summarizing air-ground signals helpfully contained a small sketch of what the two-seater Spad with such a flag might look like from the ground. The airplane crew could fire two stars to tell ground troops “I am the division plane” or six stars to ask “Where are you, mark out your first line.” Ground troops could use a combination of panels to demand a barrage, report artillery rounds falling short, or request ammunition resupply. For emergencies, they were advised to wave “…overcoats, tent canvas, handkerchiefs, newspapers, looking glasses…[their] arms, or by firing towards the ground one-star rockets.”

Some airplanes had radios but were ready to use “weighted messages” instead. Great importance was assigned to the division balloon, which, it was hoped, would have a good vista from its mooring some ten kilometers west of the front line. A dedicated phone line and a standby motorcyclist were allocated to the balloon commander. All of these important assets were to be protected by fighter airplanes directed by the X Corps. The division order did not make provisions for air defense. Field Order No. 18 was issued on 20 May, beginning a hectic week of orders, briefbacks, rehearsals, meetings, reconnaissance, amendments to orders and other preparations. MG Bullard decided that the 2d Brigade’s 28th Infantry Regiment under COL Hanson E. Ely would make the attack.

Between 22 and 26 May, the 28th Infantry withdrew to a rehearsal site some twelve miles in the rear that vaguely resembled the ground around Cantigny. Here they practiced the attack in detail while officers studied bas relief models of the actual objective. To accommodate preparations, Bullard requested and received permission to delay the attack from 25 May to 28 May. MAJ (later COL) Robert R. McCormick, commander of the 1st Battalion, 5th Field Artillery, marveled at the French method of issuing an order as a general discussion and critique among the commanders during which the plan was modified on the spot. “The meeting broke up with every officer thoroughly understanding the work before him and sharing the general confidence in the plans…”

All of this took place while in contact with an enemy who was anything but passive. Regular air attacks and artillery bombardments inflicted more than 2,000 casualties, including more than 300 killed, in the month preceding the attack. The Germans replaced the 30th Reserve Division at Cantigny with the 82d on May 16. A U.S. engineer party moving forward at night strayed into enemy territory and returned without its lieutenant, who was believed to be carrying notes and sketches from the division order. The anxiety caused by this event was much increased when German raids occurred on the division’s left and right flanks on 27 May. Although repulsed, the raids suggested the attack had been compromised.

More ominously, on 27 May the Germans opened their third major offensive of the spring, breaking through Allied lines along the Chemin des Dames ridge some forty miles south. The French First Army made immediate preparations to shift assets there to meet the new emergency, including artillery and aircraft committed to the attack on Cantigny. The decision to proceed with the attack was anything but easy, but GEN Pershing, visiting the division headquarters in Mensil-St.-Firmin amid these trials, approved the attack for the next day. Foreshadowing a technique made famous in World War II, LTC Marshall then briefed the assembled news correspondents on the plan, in part to commit them to its security.

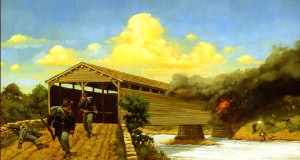

The attack the next morning proceeded much as planned. Registration of guns began at 0445. At 0545, as an early morning haze wafted over the battlefield, the preparation fires struck throughout the attack area, making Cantigny itself resemble a volcano. Just before 0645, the Schneider tanks clanked slowly forward from their hide positions in the Valle de Coullemelle to cross the American trenches at pre-selected traverses. French aircraft swarmed ahead. The 75mm gun barrage shifted onto the line of departure, roiled and blasted there for three minutes, and then moved east. All along the line, amid whistles and shouts barely audible over the din of artillery, mortars, and machine guns, doughboys of the 28th Infantry grunted up from their trenches, hefting their extra ammunition, grenades, rations, flares, shovels, and other equipment and formed into squad lines, bayonets fixed, to follow the rolling barrage.

Much to everyone’s surprise and relief, they met spotty resistance. The tanks could not enter Cantigny itself through the rubble, but they quickly eliminated several machine gun positions west and north of the village. With a few tanks stalled or stuck in shell holes, all battalions reported to have reached the objective line by 0720. Field Order No. 18 called for organizing the conquered positions into three successive lines, each corresponding to a wave of the attack. The first, farthest to the east and closest to an enemy counterattack, would be beyond Cantigny, on the eastern slope of the Cantigny plateau. The plan directed that this line would connect good observation points that “should be available” and would be lightly held as a line of surveillance by pre-designated teams including automatic riflemen.

Between 150 and 200 meters west of this line, the second wave and other support troops would construct a parallel of resistance complete with entrenchments and wire entanglements. Yet farther back, on the eastern side of the village itself, troops were to use cellars and other rubble to organize a defense anchored on three strongpoints, each aligned on a probable route of enemy counterattack. The tanks had no role in the consolidation and, according to plan, were withdrawn by their commander, Captain Emile Noscereau, at about 0800. Generally, the doughboys adhered to this scheme.

There were important exceptions on each flank, however, as well as in Cantigny. On the southern or right flank, the 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry, executed a complex maneuver involving two companies clearing the southern edge of Cantigny and the ravine to its south, while a third company pivoted to come on line with the others and connect with the stationary 26th Infantry yet further south. This maneuver succeeded, but exposed the battalion to machine gun fire from deep within the German lines near Fontaine that killed several officers. A confused German sortie of about 100 troops followed. Although quickly dispatched by a defensive barrage, these actions left the right flank less stable than the center.

On the northern or left flank, the 3d Battalion, 28th Infantry, advanced fitfully toward the objective line. Delayed by an old French position that had not been adequately breached for passage, soldiers became separated from the rolling barrage and from each other. German machine gun fire enfiladed the battalion’s advance from positions facing the French 152d Division farther north. Soldiers of the second wave became intermingled with German defenders unnoticed by the first wave and gritty hand-to-hand combat ensued. Two Schneider tanks wandered into the sector and aided the Americans briefly before retiring. This flank, too, was not as stably consolidated as indicated by initial reports of success. Indeed, two companies of the 3d Battalion would later fall back to their original positions at the line of departure, a distance of only a few hundred yards.

In the center, the 2d Battalion, 28th Infantry, had the primary task of clearing Cantigny, aided by Company D of the 1st Battalion, which cleared the southern edge and the ravine to the south. The battalion scheme called for Companies E, F, and H to advance on line, with Company H passing through the center of the village. Company H was to suppress enemy resistance and move quickly through the village to the objective line beyond, leaving the village itself to Company G and its attached French flamethrower teams, following in trail. The preparatory barrage drove most German defenders into the deep cellars and bunkers in the village, from where they resisted after Companies H and D had passed through.

As the battalion command group approached the village between Companies H and G, battalion commander LTC Robert J. Maxey went down with a mortal wound. Shortly after Maxey was hit, the Company G commander, CPT Clarence R. Huebner, arrived on the scene and assumed command of the battalion. Company G and the flamethrowers went to work on remaining pockets of German resistance, killing many and forcing the capture of nearly 100 more, but troops in the ruined village experienced ambushes and sniper fire for the next several days. With the attack apparently successful and U.S. troops consolidating their hold, the French artillery fire slackened as their batteries prepared for immediate movement south. German artillery fire against the new position increased apace.

By noon, enemy artillery and machine gun fire into what was now a shallow U.S. salient in the German line became intense. Several small counterattacks during the day met withering American rifle, machine gun, and artillery fire and were driven off. The most organized German riposte developed early in the evening mainly against the 1st Battalion’s position on the right flank. Three battalions of the German 83d and 272d Reserve Infantry Regiments emerged from woods and valleys to the east and southeast, but in sequence, allowing the Americans to halt each in turn. Casualties inflicted by this and subsequent attacks the next day, as well as incessant German artillery fire, caused COL Ely to request relief of his regiment. Instead, Brigade Commander BG Beaumont Buck and MG Bullard approved commitment of reserves to bolster Ely’s line. Companies C and F, 18th Infantry, arrived first, followed by Company D, 26th Infantry, and Company D, 1st Engineers, employed as infantry.

By 30 May, the new American position was sufficiently secure that Bullard could approve the relief. The 16th Infantry Regiment relieved the 28th that night. The fight had caused the 1st Division another 1,067 casualties—killed, wounded, missing, and gassed. The 1st Division remained in Picardy for another six weeks, but the hardest fighting had moved elsewhere as the Germans tried to pry strategic success from some portion of the Western Front. Concern over renewed German offensives in early June, and the removal of French divisions, caused the division to put both infantry brigades on the line by 8 June. On 9 June, the sector was severely shelled when the Germans launched their fourth major offensive between nearby Montdidier and Noyon, but that effort was readily contained.

1st Division troops shelled and were shelled, regularly patrolled no man’s land, and raided the German lines as the initiative passed from the Germans to the Allies and the division awaited orders. The sector was sufficiently secure that MG Bullard approved Independence Day celebrations in the form of a horse show and other competitions at the new headquarters at Tartigny. Soldiers were decorated for heroism. The 1st Artillery Brigade fired a 48-gun barrage into enemy lines in honor of the day, and a significant gas concentration that night. French troops began relieving the 1st Division on 5 July; the relief was completed on 8 July, and by 12 July, the division was assembling for its role in the Aisne-Marne Offensive. Within days, it would fight a much larger, costlier, and decisive battle near Soissons.

Cantigny made a profound statement to Germans and Allies alike. “It was a matter of pride to the whole AEF,” wrote Pershing, “that the troops of this division, in their first battle…displayed the fortitude and courage of veterans, held their gains, and denied to the enemy the slightest advantage.” Cantigny put the lie to German propaganda that had deprecated the Americans’ fighting skill. It bolstered Allied morale to hear of American troops in the line, on the offensive and succeeding. It underscored Pershing’s persistent argument that American troops were more valuable in large formations of their own than as reinforcements for the Allies. Most important, it began a record of American success powerfully amplified by the heroic stands of the 2d and 3d Divisions along the Marne just days later. Clearly, Americans could fight, and there were now nearly a million of them in France. For the first time in years, the Allies’ imagination could turn from stemming defeat to winning the war.

The officers and soldiers of the 1st Division were likely either too tired or too busy to reflect on any legacy of what they had just done, but it was profound. They had initiated the combined arms warfare and the division organization that the AEF would refine and apply at Soissons, St. Mihiel, and Meusse-Argonne and that would characterize their army’s approach to battle for the rest of the century. They had proven the mettle of officers who became important leaders of the Army into the 1940s—Bullard as an army commander, Summerall as Chief of Staff by 1929, Marshall (who reflected on Cantigny in the 1930s as he trained a new generation of officers at the Infantry School) as the World War II Chief of Staff, and many others. CPT Huebner went on to earn a Distinguished Service Cross at Soissons.

It is not too much to imagine that, as commanding general of the 1st Infantry Division twenty-six years later, Huebner recalled the orders and rehearsals of Cantigny as he used very similar techniques to prepare his old division for its destiny on Omaha Beach in Normandy on 6 June 1944. He would become the first chief of staff of U.S. European Command (EUCOM) and later serve as EUCOM’s acting commander in 1949-1950. Not all heirs of Cantigny were professional soldiers. Robert R. McCormick returned from the war a colonel, renamed his estate in Wheaton, Illinois, Cantigny to honor the battle, and built his Chicago Tribune Company into an international and multimedia giant. Among the rank and file, infantry PVT Samuel Ervin survived the war and went home to North Carolina to begin his rise to a distinguished career in the United States Senate. No wonder that the 28th Infantry Regiment took as its distinctive insignia the lion crest of Picardy and, for its nickname, “Lions of Cantigny.”