By Sergeant Major Zach Wriston, USA

The advent and development of distance education has provided accessible, affordable, and quality education to millions of Americans. Distance education can trace its roots to educators in the late 1700s publishing newspaper advertisements offering to teach shorthand through correspondence. Distance education gradually matured over two centuries before growing exponentially during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Within the broad development of America’s acceptance of distance education, the U.S. Army also adopted early forms of distance education in the early twentieth century. This article explores the Army’s historical and theoretical foundations of distance education. It will examine the historical development from traditional face-to-face education to distance learning, practical uses, and academic approaches to distance education within the Army as an educational institution. The article will also explore connections between distance education theorists, academics, and practitioners in the civilian sector and parallels with the Army.

The U.S. Army has a century of experience training and educating personnel using distance education. This history is little known or understood outside a few historians at the Command and General Staff College. Reviewing the Army’s nearly 250-year history of educating officers and enlisted soldiers will reveal the extent of early efforts, best practices, failed experiments, and more. The Army’s venture into distance education started with commissioned officers and gradually evolved to cover all ranks within the Army. The Army now uses distance education to for self-development programs, massive open online courses, interactive courses, and rigorous academic courses. The Army’s educational progress is best understood through the lens of American culture and historical efforts to modernize and professionalize the force. The Army’s educational system developed over the course of 249 years has been based on military necessity (professionalization, modernization, technology, and war), reforming the bureaucracy, public policy, and public opinion. The United States was born in an era of large standing armies. Historically, the citizens of the young nation demonstrated a “preoccupation with private gain, a reluctance to pay taxes, a distaste for military service, and a fear of large standing armies.”1 President Dwight D. Eisenhower expressed this attitude when he addressed concerns about the military-industrial complex and funding implements of war rather than funding schools, roads, or other public needs.2 Alan Millett and Peter Maslowski describe the American people’s relationship with the Army as pluralistic—that the military, and American society as a whole, is composed of “professional soldiers, citizen soldiers, and antimilitary and pacifistic citizens.” 3 Professional soldiers sustain the Army during war and peace. Citizen-soldiers answer the call, such as after Pearl Harbor or 9/11, and then return to civilian life after a relatively short period of service. Citizenry, on the other spectrum, challenges policymakers and the military, sometimes to frustration and other times to uphold the best of American values.

Military education shares many commonalities with civilian education. J.D. Fletcher and P.R. Chatelier discern three unique characteristics of military training: discipline, just-in-case, and collective training. Discipline in military terms means well-trained individual soldiers who are then further trained as a unit prepared “to enter harm’s way and perform physically and mentally demanding tasks at the highest possible levels of proficiency.” Just-in-case training recognizes the events least likely to occur and the necessity for military professionals to be prepared to conduct these unique duties due to their profession’s lethal nature. The collective nature of training recognizes that the military performs in small units and not merely as individuals. “Collective training is emphasized to an extent rarely found in nonmilitary venues.”4

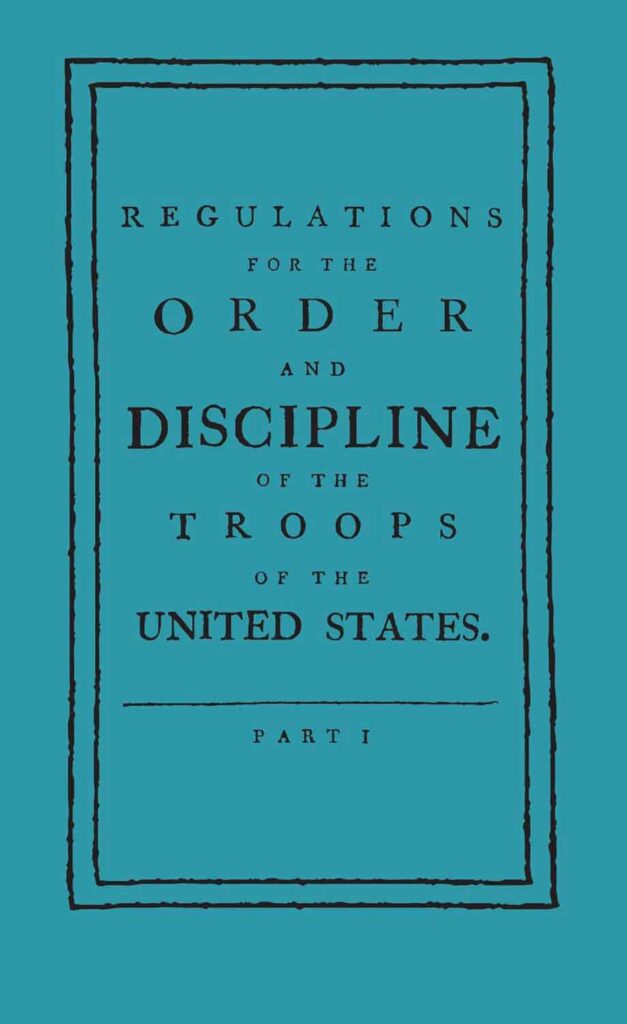

Education in what became the U.S. Army originated with the British Army teaching militia officers and soldiers during the colonial wars in North America, culminating in the British victory in the French and Indian War that concluded in 1763. During the Revolutionary War, Major General Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben created the Blue Book, which the Army used for nearly a half-century to train its noncommissioned officers (NCOs) and enlisted men. Von Steuben is credited for instilling discipline, leadership, and sound tactics into the Continental Army.5 His inspiration for writing the manual was inspired by his frustration with America’s pluralism and an American defeat in an engagement known as Baylor’s Massacre.6 According to Paul Lockhart, the defeat itself did not motivate von Steuben as much as its preventable nature and the American troops’ poor training, preparation, and performance.7 Von Steuben’s manual established the practice of self-directed instruction, small group training, and in-house training that continues today.

The Army’s introduction to formal education occurred in 1802 when President Thomas Jefferson established the U.S. Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York, as a school for training engineers and Army officers.8 Jefferson represented the peculiar culture of America as he vehemently opposed the idea of a military academy during the Washington and Adams administrations. In the years following the establishment of USMA, several states created publicly supported military schools, including the Virginia Military Institute and The Citadel in South Carolina. In addition to these state-supported institutions, several private military academies were created, such as the The American Literary, Scientific, and Military Academy (today’s Norwich University) in Vermont.

USMA was the Army’s only permanent military educational institution until after the Civil War. During General William Tecumseh Sherman’s tenure as commanding general of the Army, he oversaw the creation of schools for the Infantry and Cavalry branches. He also sustained the Artillery School and encouraged a school for engineers and a war college.9 Sherman both encouraged and was strongly influenced by the writings of Emory Upton, an 1861 USMA graduate and veteran of the Civil War who developed new infantry tactics during the conflict as a junior officer. Upton penned Infantry Tactics, The Armies of Asia and Europe, and The Military Policy of the United States, published posthumously after his death in 1881.10 According to historian Mark Stoler, “The Military Policy of the United States constituted a devastating critique of the ineffectiveness of traditional U.S. military policy and a call for drastic change.”11

Despite support from Sherman and even President James Garfield, public disinterest led to a significant lack of congressional support for Upton’s modernization and reform ideas.12 Throughout the nineteenth century, individuals such as Sherman, Upton, General Philip I. Sheridan, and Lieutenant General John A. Schofield made efforts to reform and modernize the Army by addressing outdated command structures, tactics, and personnel policies (promotion stagnation and retirement regulations continued to be problematic until changes after World War II).13 These efforts often ran headlong into political difficulties or, just as often, the Army’s own heavy-handed and frequently feuding department bureau chiefs. Educational efforts in this era focused primarily on officers, as even the best NCOs lacked educational qualifications for advancement.14 The lack of attention paid to the enlisted force represented the low standing of the enlisted soldiers in society and their lack of even rudimentary education.15 Many Americans “rejected the idea that enlisted soldiering could be a profession, a perception which had a direct political impact on the corps.”16 The pay was meager and remained so for decades until the Root reforms. Soldiers often described poor treatment from the civilians in eastern cities who accused them of being “too lazy to work for a living.”17

In his classic work, The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784-1897, historian Edward M. Coffman addresses education seven times and desertions and drunkenness over thirty times.18 The education levels of the 1800s enlisted soldier are vastly different from today’s modern enlisted soldier. Except for when the Army expanded to include citizen-soldiers during wartime, between thirty and forty percent of the enlisted force were illiterate to the point of being unable to write their own names.19 Coffman discusses the development of post schools following the Civil War and even night schools for soldiers and dependent children.20 However, twenty years after implementation, of the 137 military posts in operation, thirty-two still had no education programs and only sixty-seven percent of school children were enrolled at post schools.21 Coffman’s research of enlistment papers, diaries, and personal accounts found that enlisted personnel were much more successful at self-directed learning through the use of post libraries.22

In the history of the U.S. Army, few individuals played a more important role in the modernization and professionalization of the Army than Elihu Root. Soon after Root’s appointment as Secretary of War in August 1899 during the administration of President William McKinley, he discovered the writings of Emory Upton and directed the War Department’s posthumous publishing of The Military Policy of the United States in 1904.23

Root’s tenure in office resulted in the most pronounced reforms and modernizations to the military until legislative reforms in 1947 and 1986. Root’s efforts modernized the War Department by reorganizing it to include a general staff and restructuring the National Guard.24 His efforts also led to the creation of what became the Army Reserve in 1908. Root’s efforts to professionalize officers resulted in a renewed emphasis on education by creating the Army War College in Washington, DC, and the Command and General Staff College (CGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. In World War I, eight of the twelve senior officers to serve on General John J. Pershing’s American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) staff were CGSC graduates.25 Since their creation, graduates of these two schools have led the Army in all conflicts and wars and will continue to do in the future.

In 1908, President William H. Taft, a former Secretary of War under President Theodore Roosevelt, personally appealed to Congress for improved pay for enlisted personnel, resulting in the “first army-wide pay bill since 1870.”26 As military technology advanced in the Age of Industrialization, the demand for well-trained and educated soldiers increased. General Pershing advocated for establishing schools for NCOs during World War I but could only provide schools within the AEF overseas and not in the continental United States.27 Despite the contributions of enlisted personnel during World War I, “in June 1920, a cost-conscious Congress grouped all enlisted soldiers into seven pay grades and eliminated the ranks of master sergeant and sergeant major.”28

World War II and Korea elevated NCOs to small-unit leaders. As a result, shortly after the end of World War II in Europe in 1945, the “first school devoted to educating professional NCOs” opened in Guila, Italy.29 Brigadier General Bruce Clarke followed this action by opening an NCO course at Fort Knox, Kentucky, followed by a series of NCO academies in West Germany, Texas, Hawaii, and Korea.30 Nevertheless, despite this advance in education, there was no standardization across the Army in educational standards, curriculum, or instructor quality.

In June 1958, Congress restored the pay grades of E8 (master sergeant/first sergeant) and E9 (sergeant major). In 1965, Army Chief of Staff General Harold K. Johnson wanted to recognize the value and contributions of the NCO with the creation of the position of Sergeant Major of the Army. Johnson stated that if “we were going to talk about the noncommissioned officers being the backbone of the Army, there ought to be a position that recognizes that this was in fact the case.”31 Throughout the late 1960s to the 1980s, the Army also standardized NCO education for NCO grades, created the Sergeants Major Academy at Fort Bliss, Texas, and published The Army Noncommissioned Officer Guide. The advent of the all-volunteer Army in 1972 drove efforts to make an enlisted career competitive to those in the civilian sector “with promises of individual opportunity: marketable skills, money for college, achievement, adventure, and personal transformation.”32 The Army had finally championed the professionalization and education of officers and NCOs. This profound change led to significant developments in distance education for officers and enlisted soldiers.

The Army’s use of distance education arose from the needs of the Command and General Staff Correspondence School, which trained 5,000 active and reserve officers annually starting in 1922.33 Extension courses for reserve personnel were instituted in the 1950s and managed by the U.S. Armed Forces Institute.34 The Army continued to train personnel using distance learning through the 1970s. Beginning in the 1950s, the Department of Defense (DOD) significantly invested in computer-assisted instruction.35 Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, DOD partnered with numerous universities to develop automated teaching platforms and computer instructional design programs.36 The policy of working closely with civilian universities persists today with programs offered through the Captain’s Career Course, various Army Fellowships, and the Sergeants Major Course.

The Iron Triangle effect of cost analysis emerged in the 1970s as costs increased and developers struggled to anticipate “learner states and interactions” with the technology.37 The military also significantly contributed to the development of simulation technology to “authenticate “real-world” experiences.”38 The Army Correspondence Course Program (ACCP) originated at Fort Eustis, Virginia. The ACCP carried on the tradition of delivering paper correspondence courses covering a myriad of topics to troops across the globe. The most well-known courses were the text-based and popular yellow manuals used from the 1970s through 2010. This program trained over 100,000 annually in the United States and overseas.39 The demand for the course resulted in the Army operating one of the largest U.S. post offices in the country from Fort Eustis.40 The 1980s and 1990s marked significant policy, funding, and platform development. Steve Duncan describes the Army’s relationship with distance education as “a history of false starts, lessons learned, cultural shifts, parity of esteem and acceptability issues.”41 As a result, defense planners and policymakers developed the Army Long Range Training Plan (1989-2018) with a significant focus on transitioning from traditional residential training courses to a distance education model. Cost savings were a significant driver of the policy with the waning threat of the Soviet Union, and lawmakers expected savings of defense cutbacks to pay for social and other governmental programs.42

A significant challenge to the development of distance education was the leaders in charge and their priorities. Duncan discusses two generals who either placed restrictions on developing traditional training into distance learning courses or committed zero resources to fund distance learning.43 This attitude changed when General Dennis Reimer became the Army Chief of Staff in 1995 and led a digital revolution. Reimer fully committed himself and the Army to the 1996 Army Distance Learning Master Plan (ADLMP). The ADLMP advocated funding and resources to distance learning as a cost-effective and competitive advantage to personnel training. Reimer helped establish the Army University Access Online (eArmyU) program in 2001. The eArmyU program provided soldiers unable to attend a traditional face-to-face course with the opportunity to pursue distance education. The program connected 60,000 participating soldiers to twenty-nine colleges and universities with over 140 certificate and degree programs.44

Reimer also established a centralized knowledge management tool providing online access to approved U.S. Army training and doctrine information. In his honor, the Army named the database the General Dennis J. Reimer Training and Doctrine Digital Library (RDL). This early knowledge management tool became the current Army Training Network.45

Reimer’s effort also improved the NCO education system. In 1995, the Army conducted its pilot distance learning course for sergeants using video tele-training to educate soldiers assigned to the peacekeeping mission in the Sinai to complete the primary leadership developmentcourse. Two years later, the Army established a common core course for the reserve component at Fort Hood, Texas.46 These efforts led to more common core and multi-phase courses using distance learning for at least part of many courses, including the Battle Staff NCO Course, Basic NCO Course, and Advanced NCO Course.

By the early 1990s, Army leaders, planners, and educators consulted and studied adult education experts as they developed Army educational programs. One of the earliest examples of the Army adopting academic adult educational theories and ideas is present in Michael Barry and Gregory B. Runyan’s 1955 literature review of the Army’s application of distance education.47 This literature review during the Reimer era connects Michael G. Moore’s definition of distance education to the Army’s educational delivery systems, the effectiveness of distance learning, and future applications.48 In a 1995 article in The American Journal of Distance Education, Barry and Runyan explore the various mediums available for distance education and demonstrate the effectiveness of distance learning compared to traditional face- to-face methods using multiple empirical studies.49 One finding in their research connects communities of inquiry and the importance of teacher presence in the learning process.

In 1994, Army Chief of Staff General R. Gordon Sullivan consulted with Margaret Wheatley, a social scientist, about transforming the Army into a learning organization.50 Anthony J. DiBella’s research examines whether the Army exhibited practices and behaviors of a learning organization during the Army’s transition to counter-insurgency operations.51 DiBella, a profesor of Strategic Leadership at National Defense University, concludes that an integrated systems approach, where leaders understand how the Army learns, will improve performance as a learning organization.52

The Army continued to build its distance learning capabilities throughout the early 2000s. The operational tempo of fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan created backlogs in school attendance and greater demand for distance education options. In 2004, combat operations led to the modernizing of NCO residential and distance courses to reflect actual combat realities.53

The Army created online courses through multiple sites, such as Army Learning Management, Army Safety, Joint Knowledge Online, and Army Knowledge Online. The courses were self-enrolled and self-directed. The number of courses resembled the access of the massive open online course phenomenon that would occur between 2008 and 2012. The challenge for the Army was duplicating efforts, as its primary focus was on warfighting.

A new era of professionalization started under General Martin Dempsey, who led the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) from 2008 to 2011. During his time at TRADOC, General Dempsey made “The Army Profession” the key objective of the TRADOC Campaign of Learning.54 He decentralized TRADOC’s training development process, streamlined publication updates and revisions, and determined that TRADOC Headquarters would focus on future efforts.

In 2010, the Army made substantial changes to its distance education program. The Army Distributed Learning Program replaced the Army Correspondence Course Program. Structured self-development online courses were introduced between all levels of residential professional military education. The Army also improved its knowledge management with a publishing directorate capable of managing revised and new doctrinal and training publications.

Perhaps the most significant development for the U.S. Army’s education system was the establishment of The Army University on 7 July 2015, which “integrates all of the professional military education institutions within the Army into a single educational structure modeled after many university systems across the country.”55 The advent of The Army University increased and legitimized Army school accreditation into college credits and degrees.

A final milestone in distance learning occurred on 1 February 2019, when the Army transitioned from structured self-development online courses to distributed leader course (DLC) online courses. DLC consists of six courses from junior enlisted to sergeants major, with the purpose of “being progressive and sequential.”56 The courses provide real-world interactive scenarios with some ambiguity to challenge the learner’s understanding of the human/dimension, leadership, and profession.57 The speed of transition and development from the Army’s introduction to distance learning to today is significant and lays the groundwork for future research.

While much documentation exists for distance learning efforts in the past twenty-five years, little documentation exists for the Army’s earliest efforts. Some websites indicate that the Army used correspondence courses as early as 1874 but lacked supporting documentation. The CGSC produced a one-page document with ten bullet points documenting a historian’s summary of distance education milestones since 1922.58 However, it did not include references or other documentation. Researchers can improve upon existing records of the Army’s use of distance education by visiting individual Army schools and museums nationwide.

Cost-effectiveness and the ability to teach soldiers over distance are the driving factors in the literature examined for this paper. By the mid-1990s, Army researchers and educators communicated the ideas of Michael G. Moore and other academics about the value of distance learning to achieve educational goals. Future researchers could investigate archives to determine connections to earlier adult educators like Charles Wedemeyer or Otto Peters.59 Daniel K. Elder is a retired command sergeant major who has dedicated more than a quarter of a century to researching the history of Army enlisted and noncommissioned officer education. His research fits the pattern of military training described by J.D. Fletcher and P.R. Chatelier.60 Elder has composed an impressive digital catalog of documents related to the enlisted force’s career, history, and education that could provide the foundation for essential studies in distance education.61

The Army offers an excellent research field to consider distance education in the workplace. The Department of Defense employs more workers than Walmart or Amazon.62 Research in this area could examine the Army as a whole, or perhaps the National Guard or Army Reserve, to improve understanding of workplace applications in the future. Workplace learning and DiBella’s efforts to understand the Army as a learning organization open the door for many valuable research opportunities.

Early reformers for Army education such as Emory Upton and Elihu Root have significant bodies of study. Future researchers could profile Generals Reimer or Dempsey to illustrate Army leaders’ commitment to reform and modernizing distance education. General Dempsey frequently authored white papers to guide professionalization efforts, and since retiring, he published two books on leadership.63 This is also an opportunity to study army leaders and their use of adult learning theories and concepts.

The U.S. Army has a two-and-a-half-century history of educating officers, noncommissioned officers, and enlisted personnel. This article explored the Army’s historical and theoretical foundations of distance education. The culture of the American public tempered the Army’s approach to education and modernization. The Army has connected adult education and distance education theories to practice in the last twenty-five years. The speed and capability with which the Army has integrated distance education into its educational process in the last ten years is unprecedented and allows greater future research opportunities.

Endnotes

- Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Simon and Shuster,

- 1994), xii.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, “The Chance for Peace,” Recorded at the American Society of Newspaper Editors, Washington, DC, 16 April 1953. The Eisenhower Presidential Library. https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/eisenhowers/speeches; Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Farewell Address to the American People,” recorded at the White House, 17 January 1961, The Eisenhower Presidential Library. https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/eisenhowers/speeches

- Millett and Maslowski, For the Common Defense, xii.

- J.D. Fletcher and P.R. Chatelier, “An Overview of Military Training.” Institute for Defense Analyses (October 2000): II-1-II-4. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA408439.pdf

- Department of the Army, The Noncommissioned Officer’s Guide, TC 7-22.7 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2020), 1-2.

- Paul Lockhart, The Drillmaster of Valley Forge. The Baron De Steuben and the Making of the American Army (New York: HarperCollins, 2008), 183.

- Ibid., 183.

- Christine Coalwell, “West Point: Jefferson’s Military Academy,” Monticello Newsletter 12 (Winter 2001): 2. https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thom- as-jefferson-encyclopedia/united-states-military-academy-west-point/

- Millett and Maslowski, For the Common Defense, 271.

- Emory Upton, The Military Policy of the United States (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1912).

- Mark Stoler, George C. Marshall: Soldier-Statesman of the American Century (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1989), 19.

- Stephen E. Ambrose, Upton and the Army (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992), 118.

- James Morris, America’s Armed Forces: A History, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996), 147-52.

- Edward M. Coffman, The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784-1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 203.

- Ernest F. Fisher, Guardians of the Republic: A History of the Noncommissioned Officer Corps of the US Army (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001), 94.

- Department of the Army. The Noncommissioned Officer’s Guide, 1-8.

- Fisher, Guardians of the Republic, 94.

- Coffman, The Old Army, 507.

- Ibid., 17, 141, 203.

- Ibid., 133-35, 175-78.

- Ibid., 323.

- Ibid., 175-77.

- Ambrose, Upton and the Army, 155.

- Millett and Maslowski, For the Common Defense, 326-30.

- Richard W. Stewart, ed., American Military History, Volume II, The United States Army in a Global Era, 1917-2008, CMH Pub 30-22 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2010), 23. https://www.history.army.mil/html/books/030/30-22/index.html

- Donald W. Hogan, Jr., Arnold G. Fisch, Jr., and Robert K.Wright, ed., The Story of the Noncommissioned Officer Corps: The Backbone of the Army (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2009), 18.

- Ibid., 19.

- Daniel K. Elder, Mark F. Gillespie, Glen R. Hawkins, Michael B. Kelly, Presto E. Pierce, ed., The Sergeants Major of the Army (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2003), 4.

- Department of the Army. The Noncommissioned Officer’s Guide, 1-13.

- Ibid., 1-16.

- Elder, Gillespie, Hawkins, Kelly, Pierce, ed., The Sergeants Major of the Army, 6.

- Beth Bailey, America’s Army: Making the All-Volunteer Force (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009), ix.

- Command and General Staff College, “General History of the Department of Distance Education,” (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Command and General Staff College, 2013). https://armyuniversity.edu/cgsc/cgss/files/Brief%20DDE%20History%20%28002%29.pdf

- Peggy L. Kenyon and Timothy Flora, “Distance Education in the Armed Forces,” in Handbook of Distance Education, 4th ed., Michael Grahame Moore and William C. Diehl, ed. (New York: Routledge, 2018), 474. https://doi-org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.4324/9781315296135

- J.D. Fletcher, “Education and Training Technology in the Military.” Science, 323,7 (2009), 71. DOI: 10.1126/science.1167778

- Ibid., 72.

- Ibid., 71.

- Ibid., 73.

- Steve Duncan, “The US Army’s Impact on the History of Distance Education,” Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 6,4 (2005), 398. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ875019

- Fred Saba, “Introduction to Distance Education: The US Military,” Distance-Educator.com. January 19, 2014, https://distance-educator.com/introduction-to-dis- tance-education-the-u-s-military/

- Duncan, “The U.S. Army’s Impact on the History of Distance Education,” 404.