Written By: By John E. Fahey

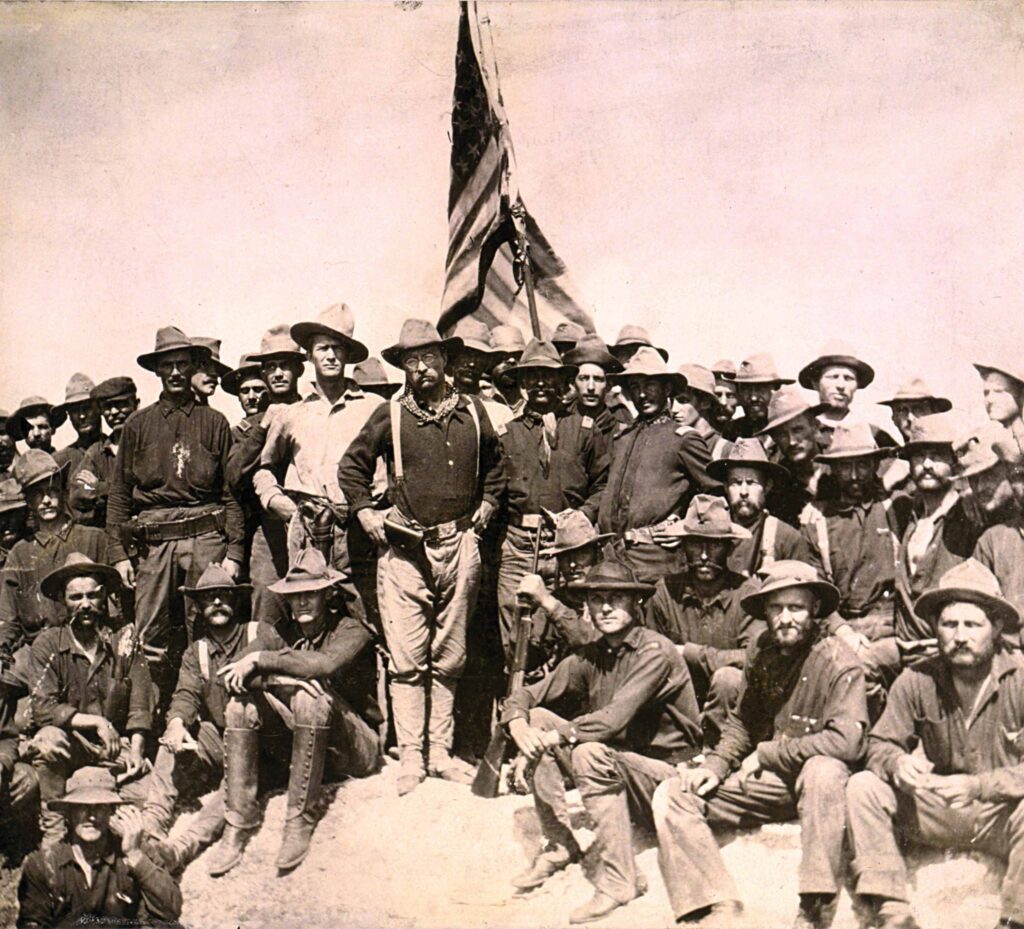

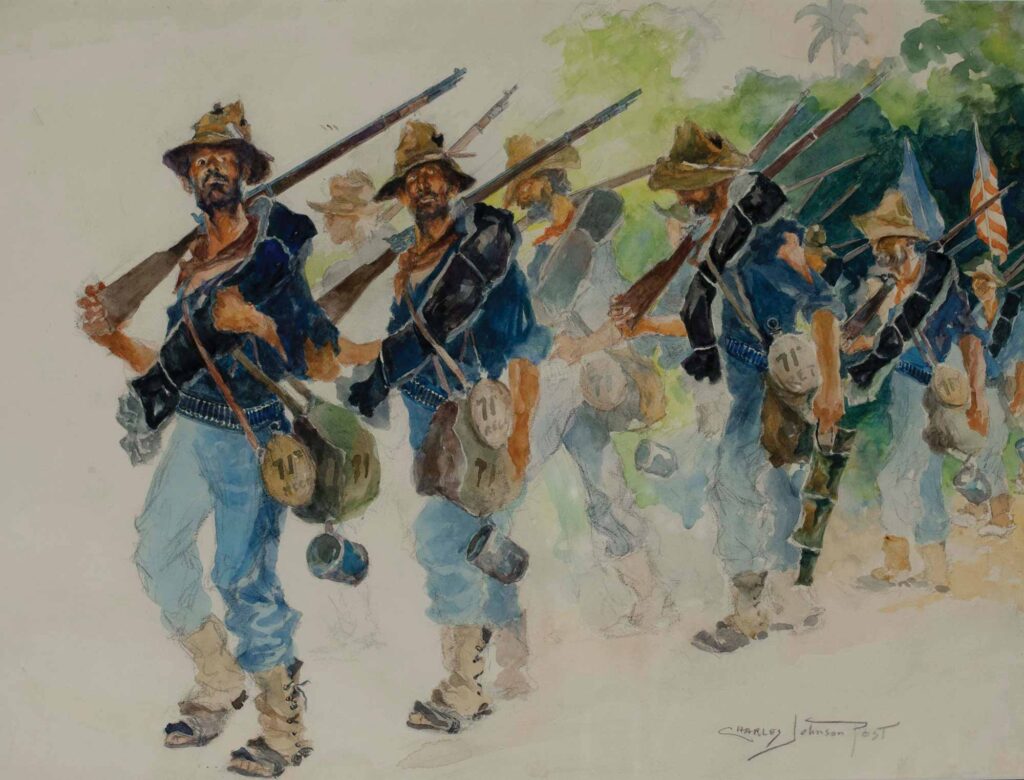

On 1 July 1898, thirty-nine-year-old former Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt led dismounted cavalrymen of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment up San Juan Hill under heavy fire. There he shot and killed a Spanish soldier using a Colt double-action revolver salvaged from the sunken battleship USS Maine.

As the stuff of legends, Teddy’s “Crowded Hour” sold books and helped to make him President, but the story often lacks context. For example, Roosevelt’s Rough Riders actually advanced up Kettle Hill and soldiers from the U.S. 10th Cavalry—an African American unit—were the first to reach the top. Perhaps most importantly, Roosevelt and the rest of the U.S. Army’s V Corps were there in Cuba to assist the U.S. Navy. The entire Santiago Campaign was intended to capture or flush out Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete’s fleet. As a result, coordination between the Army and Navy was critical for success.

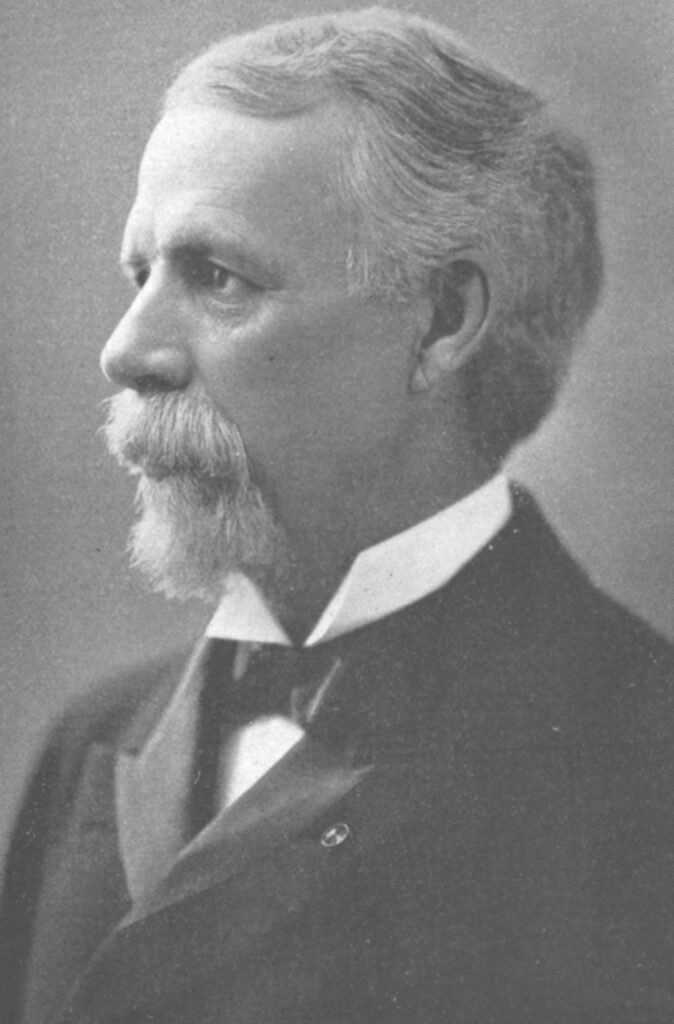

Unfortunately, the U.S. military lacked a coherent doctrine or command structure for joint operations in 1898, relying instead on personal coordination between independent Navy and Army commands. While this worked well enough in Puerto Rico and the Philippines, conflicting expectations and personal animosity between the North Atlantic Squadron’s Rear Admiral William T. Sampson and V Corps’ Major General William R. Shafter led to bitter recriminations between the commanders and their partisans.

Secretary of War Russel A. Alger wrote in his memoirs, “Unfortunately, the relations between General Shafter and Admiral Sampson during the Santiago Campaign were not at all times of the most cordial nature.” While the campaign was a success, coordination between the services broke down halfway through it, resulting in disjointed and poorly synchronized action and mutual reproach after the war. Joint operations in the Santiago Campaign illustrate the relative capabilities of the Army and Navy in 1898, the importance of personal connections, and the dangers of unclear command relationships. They also show how Army-Navy cooperation has become more effective over the last 125 years.

The United States had a long interest in Cuba. During the antebellum era, the island was targeted by Southerners wanting to add another slave state, and gun runners from the United States repeatedly tried to seize the island both before and after the Civil War. Meanwhile, Cubans themselves fought long and often to free themselves from Spanish rule. While Spain successfully crushed insurrections in the Ten Years War (1868–78) and the Little War (1879–80), its unpopularity with the Cuban people remained unchanged. José Martí leveraged the support of Cuban exiles to start another insurrection in 1895 that quickly engulfed the island.

Despite the resistance, a series of governments stubbornly held onto Cuba, seeing it as an inseparable piece of Spain and the last remnant of the Spanish Empire. Americans held conflicting attitudes on the Cuban conflict, but these intensified as General Valeriano Weyler took charge as Governor-General of Cuba in January 1896. He introduced a brutal system of reconcentration that forced Cuban civilians into Spanish-controlled camps and villages. Weyler’s policies killed tens of thousands of Cubans and sparked widespread public outcry in the United States. While President Grover Cleveland proved reluctant to intervene in Cuba, newly elected William McKinley was open to the possibility. He dispatched the USS Maine, a second class battleship, to Havana to monitor U.S. interests on the island. Maine arrived on 25 January 1898.

Unfortunately, the Maine exploded on 15 February, killing 266 American sailors. Modern examination of Maine’s wreck has conclusively shown that the ship was destroyed by an internal malfunction, probably a coal bunker fire.

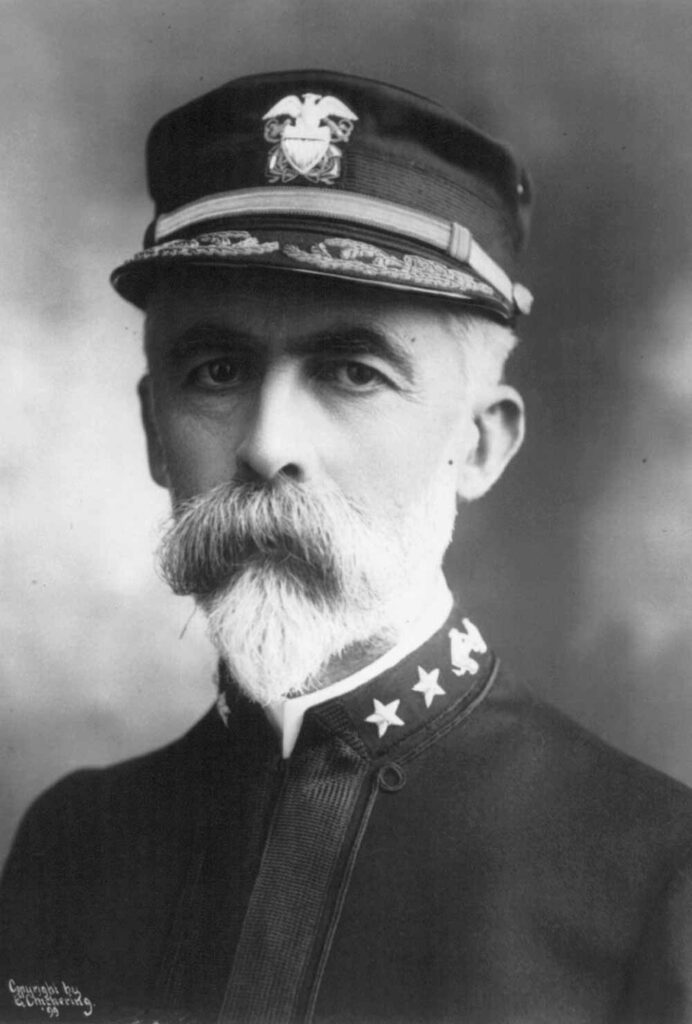

However, many Americans, especially so-called “yellow journalists” who wrote for the New York Journal and the New York World, blamed Spain. McKinley, Secretary of the Navy John D. Long, and others refrained from judgment until a court of inquiry, led by then-Captain William T. Sampson, blamed Maine’s loss on a mine.

The court’s findings, released on 20 March, made war all but inevitable. Congress issued an ultimatum on 19 April, declaring Cuban independence. Spain declared war on 23 April and Congress did likewise two days later. To fight Spain effectively, the Army and Navy needed to work together. Fortunately, the Navy was in the middle of a period of rapid expansion and innovation. In the 1880s and early 1890s the “New Steel Navy” introduced metal cruisers and the first U.S.-built battleships. By 1898, the Navy had seven major combatant ships and dozens of smaller ships. As the fleet expanded, officers updated doctrine, particularly under the influence of Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan. Well-trained and rapidly improving, the Navy was prepared to fight Spain.

The Army, though also modernizing its weapons and doctrine, was still a relatively small force of 28,000 men, unexpanded since the 1870s. The Army had stayed busy after the Civil War fighting and forcibly relocating Native Americans from their homelands in the western United States. These actions, though consequential for the United States, did not prepare the Army for a large-scale conflict against a European power.

As the Army modernized, it opened a series of branch schools and the Military Intelligence Division in the 1880s and 1890s, but there was little if any war planning or coordination between bureaus. By way of contrast, the Naval War College, which opened in 1884, justified itself largely as a center for strategic analysis and wargaming.

As Spain attempted to suppress the Cuban insurrections of the 1890s, the Naval War College worked out several war plans. Naturally, it predicted that the Navy would have the starring role, with the Army used to mop up any remaining resistance.

In 1896, Captain Henry C. Taylor argued that the Navy should quickly attack Havana, establish a blockade, capture Cienfuegos and other points, and occupy them with the Army. He hoped that “with vigorous preparation, and harmonious concert of action between the Army + Navy, these movements can be …completed” soon after the declaration of war. Later that year, Lieutenant William Kimball argued that the United States should use “its superior sea power” to blockade and harass Spanish possessions as the cheapest, least dangerous, and quickest way of “wounding the prestige of Spain, of crippling her revenues and of thus bringing her to treat for peace.”

If necessary, the Army could land a force in Cuba and take Havana to force a surrender. Rear Admiral Francis M. Ramsey thought the Army should be even less active. He assumed that after the Navy defeated the Spanish fleet, a blockade would starve the Spanish garrison on Cuba, letting the Army simply occupy an already defeated Spanish possession. Lacking any Army war planning, these concepts would guide American actions during the war. However, operations involving both Army and Navy would be complicated by both services’ lack of doctrine or experience working together.

The most recent joint operations had taken place in the Civil War, and though institutional memory remained, this was no replacement for practice or formal command arrangements. Complicating joint operations, both Army and Navy lacked centralized staffs, relying instead on a system of bureaus that answered to the Secretaries of War and the Navy, respectively. This system could work, but it needed good personal relations and a clear objective to function well. As America geared up for war with Spain in March and April, the Departments of War and the Navy hurried to mobilize resources and plan upcoming operations. The Army, however, did not do much before mid-April, assuming that the service would not be needed in the early stages of the war. Meanwhile, Army and Navy commands tried to hammer out the details of a campaign against Spain. In March, Secretaries Alger and Long formed a tiny Army and Navy War Board. On 19 April, McKinley met with the board.

Navy Captain Albert S. Barker was able to report that the fleet was ready for war. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Wagner, on the other hand, told the McKinley that the Army would turn into a mob if deployed without more training. The next day, McKinley met with Long, Alger, and a few leading officers from both services.

After hearing the state of the War Department, Long wrote in his diary that “at present it seems as if the army were ready for nothing at all.” He concluded that “at any event the burden is likely to fall upon the Navy.” In April, McKinley issued a call for volunteers, and soon hundreds of thousands of men were organized into volunteer units to support the Regular Army. By early May, a war conference at the White House agreed that the Army should assemble 50,000 men and transports to invade the north coast of Cuba. The expeditionary force would be protected by the Navy. This left a lot of open questions about transportation and coordination as both Army and Navy would operate transports during the campaign. While convoys would be coordinated and protected by the Navy, the Army’s chartered transports were not always responsive to fleet instructions.

On the other hand, the Navy saw convoy protection as a secondary mission. As Secretary Long reminded Alger on 31 May, the Navy “will be prepared to furnish all the assistance that may be in its power” but its priority was defeating the Spanish fleet. As the Army assembled, the White House decided that there would be no overall commander for the Cuban expedition. Instead, independent Navy and Army forces would just have to coordinate their actions, with any conflict resolved by civilian authorities. However, when Long proposed landing sites, Alger grumbled, “I beg to reply that the major-general commanding the expedition will land his own troops. All that is required of the navy is to convoy and protect with the guns of the convoy while the military forces are landed.” Soldiers gathered in Florida and Georgia throughout April and May. Meanwhile, the North Atlantic Squadron looked for Admiral Cervera’s fleet, which was thought to be on the way to the Caribbean. Finding Cervera took longer than necessary, but by 29 May, Sampson’s ships blockaded Santiago, with Cervera in the harbor. At this point, the Spanish fleet became the main strategic focus of the Cuba campaign. Unfortunately, Santiago was a well-defended harbor with coastal fortifications and a narrow, mined entryway.

The Navy would need Army help to eliminate the fleet. On 30 May, Adjutant General Henry Clark Corbin ordered V Corps commander Shafter to land near Santiago. Corbin emphasized, “You will cooperate most earnestly with the naval forces in every way.” According to the Army’s Commanding General, Major General Nelson A. Miles, Shafter’s objective was “to capture [the] garrison at Santiago and assist in capturing the harbor and fleet.” Sampson hoped the corps would arrive quickly, but it took a great deal of time to load up transports in Tampa, Florida. On 8 June, Shafter reported that “the difficulties encountered here have been almost insurmountable. Anything like quick loading is impossible, from the fact that wagons [cannot] be driven within nearly a mile of the wharf…Except when time is no object it should not be attempted to load more than 5,000 men at this place at one time.” Frustrated by waiting for Shafter, Sampson used Marines to capture Guantanamo Bay as a coaling station on 10 June. Briefly delayed by rumors of a Spanish naval force near Florida, thirty packed transports finally pulled out of Tampa on 14 June headed for Santiago.

The transport fleet rendezvoused with Sampson’s blockading fleet on 20 June. Unable to force their way into Santiago Harbor, Sampson and Shafter agreed to land at Daiquiri, fourteen miles east. This decision has been disputed for years. Sampson and Flag Captain French E. Chadwick met with Shafter and Cuban guerrilla General Jesus Rabi on 21 June. According to Navy accounts, Shafter promised to attack Morro Castle, Santiago’s key coastal defensive position, instead of the city itself, which lay a short distance inland. Admiral Sampson’s report stated that Shafter told him that he had “no intention of attacking the city proper, that [the harbor entrance] was the key to the situation.” Shafter disagreed, later claiming that he never intended to attack the coastal defenses. As Shafter complained to Brigadier General Corbin in December, “It is true that the navy did, upon meeting me, urge an assault upon the enemy near the mouth of the harbor of Santiago; but in my opinion this was impracticable, and any general fitted to command troops in war would not have adopted the suggestions.”

However, Navy officers left the meeting convinced Shafter intended to attack the harbor defenses, which indicates that Shafter failed to communicate his true intentions. As it turned out, rather than follow the coast for an attack on Morro Castle, Shafter chose to head straight inland for Santiago, likely due to a desire to quickly finish the campaign and play a role independent of the Navy. V Corps started to go ashore on 22 June, but did not inform Sampson of the campaign plans until the 25 June at best.

This confusion lay in the future, though, as V Corps landed. Daiquiri was barely a port, so the corps had to disembark via small boats. The Navy bombarded Daiquiri for about an hour before troops landed. The Army brought 153 small boats on its transports, but the Navy’s steam-launches proved far more effective.

As Lieutenant Colonel John Miley reported, “The navy continued to give their assistance until all the troops were ashore, disembarking about three-fourths of the whole command. The small boats belonging to the transports were used as well as those furnished from naval vessels, but all these boats were towed ashore in strings by the naval steam launches.” Landing V Corps at Daiquiri alone proved unwieldy, so the Americans expanded operations to nearby Siboney as well. On 25 June, Shafter reported, “with assistance of navy disembarked 6,000 men yesterday and as many more to-day.” He added, “The assistance of the navy has been of the greatest benefit, and enthusiastically given. Without them I could not have landed in ten days, and perhaps not at all, as I believe I should have lost so many boats in the surf.”

Despite Shafter’s thanks, the landing itself was fairly chaotic. Lieutenant John J. “Black Jack” Pershing wrote about it later: “Everything was in the direst confusion. No one seemed to be in command and no one had any control over boats, transportation nor anything—and it was only by the individual efforts of the officers of the line that order was brought out of chaos.” Like most of the ships, Roosevelt’s transport simply threw its horses overboard, hoping they would be able to swim to shore. For the men, he used help from the converted yacht Vixen. The ship was commanded by Roosevelt’s former aide, Lieutenant Alexander Sharp, who proved eager to help. Despite the problems, Shafter’s corps, with Navy support, managed to get 16,000 reasonably well-supplied Americans to Cuba by 26 June, a remarkable achievement considering the organizational challenges and timeline involved.

Within days of the landing, Shafter’s troops fought skirmishes at Las Guasimas and advanced on El Carney and San Juan Hill. There, on 1 July, his soldiers captured entrenched Spanish positions at the cost of over 400 killed, wounded, and captured. Captain Chadwick later noted with regret that the Army did not ask for naval gunfire support on the advance to Santiago. He blamed not the “want of good will, of which there was plenty, but…the want of any general staff system in both the war and navy departments.” Regardless of the cause, V Corps reached the outskirts of Santiago at the end of its strength. Faced with the prospect of either a prolonged siege in yellow fever season, or a costly assault against Santiago, Shafter wrote to Sampson on 2 July, asking the fleet to finish the campaign by forcing its way into San Juan Harbor. Shafter stated, “I urge that you make [an] effort immediately to force the entrance to avoid future losses among my men which are already very heavy. You can now operate with less loss of life than I can.” Sampson refused, pointing to Spanish coastal defenses, mines, and Cervera’s intact fleet in the harbor. He recommended that Shafter attack the coastal forts to clear the way for a naval attack.

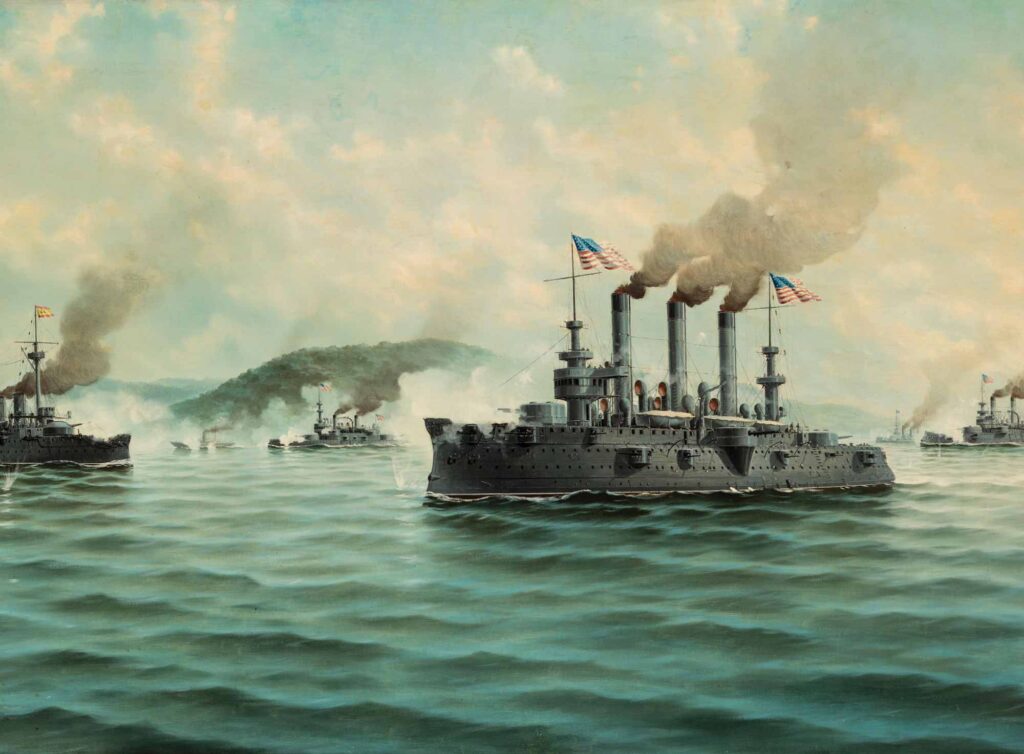

Fortunately for Sampson and Shafter, Cuba’s governor, General Ramón Blanco y Erenas, wanted Cervera to run the American blockade. Cervera predicted that the American fleet would make short work of his cruisers, but Blanco overrode him, arguing that surrendering an intact fleet would be disastrous to Spanish morale. Cervera made the attempt early on 3 July, and was predictably crushed by overwhelming American firepower at the Battle of Santiago Bay.

All four Spanish cruisers and the two destroyers were sunk or run aground, with the loss of only one American killed. Interestingly, Admiral Sampson missed the battle as he and his flagship, USS New York, were en route to meet with Shafter when Cervera attempted to escape. With the Spanish fleet utterly destroyed, Santiago lost its strategic significance. Shaken by his losses, Shafter considered withdrawing entirely, but held San Juan Heights on the advice of Secretary Alger.

Over the next weeks, Sampson and Shafter’s already shaky relationship deteriorated rapidly. On 4 July, frustrated by the Navy’s refusal to force the harbor, Shafter wrote to Sampson, wondering if the Army could use a transport “dragging an anchor to catch torpedo connections.” Facing a looming wave of disease, Shafter argued that the Navy needed to “break into the harbor at once.” Sampson complained to Secretary Long that this request showed a “complete misapprehension of the circumstances which had to be met.” The next day, Shafter wrote Samson multiple times, including a telegraph saying that the “Navy should go into Santiago Harbor at any cost. If they do I believe they will take the City and all the troops that are there. If they do not, the country should be prepared for heavy losses among our troops.”

Lacking an overarching military authority, Sampson and Shafter asked their chains of command to resolve the problem. Alger and Long went to President McKinley who unhelpfully replied that Sampson and Schley should “confer at once for cooperation in taking Santiago. After the fullest exchange of views they should be left to determine the time and manner of attack.” A few days later, Shafter, frustrated after consulting with Sampson, reported that the Navy was “disinclined to force entrance except as a last resource.” Instead the fleet would bombard Santiago in the hopes of forcing a surrender. Meanwhile, the press and Army began to insinuate that the Navy was cowardly, an accusation that Sampson resented, telling Long, “It is not so much the loss of men as it is the loss of ships which has, until now, deterred us from making a direct attack upon the ships within the port.”

Shafter’s irritation with the Navy spread to the logistical system. Supply and transport delays meant fewer reinforcements would reach Shafter. Shafter blamed the Navy for some of the problems. In the middle of a request for more stevedores and medicine, he told Corbin, “Two steam launches should be bought. Too much trouble to get things from [the] navy, and we have but partial control of them when we do get them. This is not a matter to be put off.” Shafter reiterated this point to Secretary Alger: “The obtaining of launches from the navy was not satisfactory, and I prefer calling on them as little as possible.” Meanwhile, Captain Caspar F. Goodrich, of the auxiliary cruiser St. Louis, wrote in exasperation, “…our sister branch…is a spoiled child and takes every exertion on our part as a matter of course.” Sampson and Shafter’s bad relations spread to Washington. During a meeting with McKinley on 13 July, Alger bemoaned the slow pace of the campaign in Cuba and complained about the Navy.

Secretary Long fumed to his diary that: …we have furnished him transports to carry [Alger’s] men, on account of his own neglect in making provision for transportation. We have landed them; have helped him in every way we can; and have destroyed the Spanish fleet. Now he is constantly grumbling because we don’t run the risk of blowing up our ships by going over the mines at the entrance of Santiago harbor and capturing the city, which he ought to capture himself… [Captain Alfred Thayer] Mahan, at last, lost his patience and sailed into Alger; told him he didn’t know anything about the use or purpose of the Navy, and that he didn’t propose to sit by and hear the Navy attacked. It rather pleased the President, who, I think, was glad of the rebuke.”

While tempers simmered, Shafter was negotiating for the Spanish garrison’s surrender. As both sides slowly worked out acceptable conditions, disease spread among the Americans and starvation crippled the Spanish. Sampson attempted to speed things along by bombarding the city, but to little effect. Major General Miles joined Shafter in person on 12 July. Miles wrote to Sampson on 16 July that the Spanish intended to capitulate and that terms had been agreed to. Shockingly, though, Miles did not invite Sampson or any other naval representatives to the capitulation ceremony. Captain Chadwick was present on 16 July, and “demanded” to sign, but Shafter would not allow it. Sampson correctly saw this as a grievous insult, writing the next day to Long, “I had understood that General Shafter and myself should sign [the] capitulation jointly, as were so acting under the orders of the President; but General Shafter refused upon arrival of my representative.” Shafter also excluded Cuban guerrilla leaders from the surrender negotiation.

The Santiago garrison capitulated on 17 July, but that did not stop Army and Navy leaders from arguing. Sampson still wanted to sign the paperwork, but on 19 July, Shafter told Alger, “…it is now too late for Admiral Sampson to sign articles of capitulation. They were completed three days ago.” A few days later Sampson contacted Shafter again, noting that Secretary Long had authorized him to sign the papers. Shafter responded, “I do not acknowledge the authority of the Secretary of the Navy in the matter in which you wire me.” He went on to explain why he had not allowed a Navy representative to the capitulation: “I shall protest to the Secretary of War against your signature to [the capitulation] document. I respectfully invite your attention to the fact that no claim for any credit for the capture of Cervera and his fleet had been made by the Army, although it is a fact that the Spanish fleet did not leave the harbor until the investment of the city was practically completed, and Cervera had sufficient losses on land on July 1 and 2.” Commenting on this strange justification, Chadwick wrote later that Shafter’s refusal to include the Navy in the capitulation signing was “probably the only known instance of so prominent a departure from usage in combined operations.”

Shafter’s complaints over recognition of the Army’s role in the naval Battle of Santiago Bay illustrates the poor relationship between Army and Navy leadership by July 1898. Some of this is natural. Overwhelmed by the losses among his own men, struggling for supplies, and facing a wave of disease, Shafter resented the Navy’s refusal to take risks to end the campaign. The fact that Sampson’s battleships were essentially irreplaceable and were needed in the face of the other Great Powers hardly mattered to him. The disagreement also spoke to a deeper issue of honor and credit. Much of military, indeed, American masculine culture, revolved around honor. Arguments over the surrender were really arguments over credit for the victorious Santiago Campaign.

Unsurprisingly, the issues and arguments of the war lingered after the conflict. Sampson told his story in the Army and Navy Register, claiming that Shafter had agreed to attack the forts; Shafter disagreed publicly with Sampson’s claim. In his account, Chadwick called the whole dispute a “somewhat disagreeable incident” that pointed to “the necessity of co-ordination in military action, and our almost absolute want of machinery at that time to effect this.” Despite many challenges, Shafter and Sampson succeeded at destroying Cervera’s fleet and capturing Santiago. Though V Corps suffered from disease and mismanagement, it successfully withdrew from Cuba shortly after the harbor was taken. Meanwhile, the Army and Navy worked together much better in Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Spain surrendered those islands to the United States on 14 September and acknowledged Cuba’s independence.

Though victorious, this short war left a bad taste among some. President McKinley, in the face of public pressure, investigated Army procurement, supplies, and logistics. Secretary Alger became a lightning rod for criticism and was forced to resign in July 1899. Major General Miles became embroiled in his own dispute with Alger as well and found himself sidelined. The Navy, though scandalized by the Sampson-Schley dispute, remained in generally high regard among the American public. It also benefited from the care of enthusiastic navalist Theodore Roosevelt after he became President in 1901. The service made some changes in response to its experience with the Army. Most significantly, the Navy expanded the Marine Corps and its role, so that the fleet would have control over its own landing force rather than having to rely on the Army.

In addition, Sampson and other officers begged for new regulations and clearer command relations when dealing with the Army. Before leaving Santiago, Sampson asked for the United States to adopt British joint doctrine and regulations. As he explained, “In view of the close relations of the Army and Navy which must exist in such operations as the present and to avoid friction specific regulations governing the combined action of the two services are necessary.” Navy officers were particularly irritated by the Army’s control over troop transports. Captain Mahan wrote to Admiral George Dewey in 1906 and stated that “Everything connected with transportation is a particular feature of maritime activity; when of military transportation, of naval activity. Internal discipline of a ship, and proper control of her movements in a convoy, can only be insured by naval organization, and naval command. The committing of [the] transport service to the Army is radically vicious in theory, and directly contrary to the practice of the most experienced nation, Great Britain. It may result disastrously.”

Both services instituted reforms in the years after the Spanish-American War. Elihu Root, Alger’s successor as Secretary of War, introduced the General Staff in 1903. The Navy proved unable to create a true general staff, but did form the General Board composed of bureau chiefs, senior admirals, and ad hoc experts which guided Navy design, procurement, and strategy up to World War II. A joint board was formed in 1903, designed to coordinate technology, intelligence, and planning between the Army and Navy, though its influence waxed and waned over the years. Significantly, neither service introduced significant changes to joint doctrine until the lead-up to World War II. Perhaps this is due to the relative lack of consequences for poor inter-service relations in the Santiago Campaign.

Though mistakes were made, the relative weakness of Spanish rule in Cuba meant that the United States won handily despite Sampson and Shafter’s disdain for one another. Regardless of the outcome, the Santiago Campaign is an important example of the need for clear chains of command, defined objectives, good personal relations between the services, and senior commanders willing to intervene when subordinates are squabbling. Joint operations are inherently complex, and not every opponent is as forgiving as Spain’s forces in Cuba.