Edited by Philip M. Smith.

College Station: Texas A&M University Press. 2022.

ISBN 978-1-64843-066-4.

Illustrations. Appendix. Notes. Index. Pp. xi, 273.

$35.00.

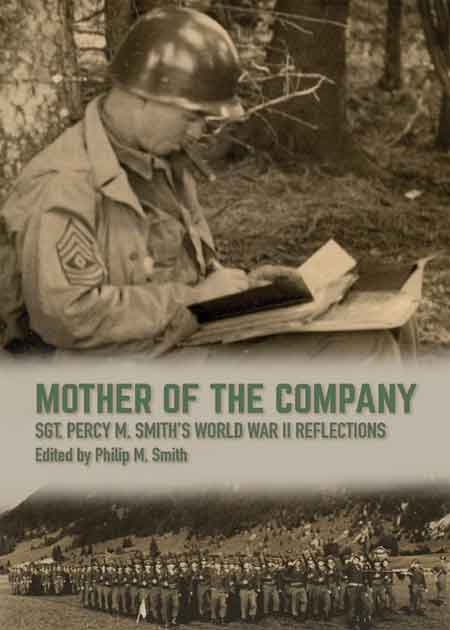

Mother of the Company reflects a son’s desire to share his first sergeant father’s war experiences in the European Theater with a modern audience eighty years removed from World War II. Philip Smith chronicles his father’s experiences through a collection of unpublished personal narratives punctuated with 214 letters the first sergeant sent home to his wife in Jacksonville, Florida, during the war.

First Sergeant Percy C. Smith served about two-and-a-half years in the U.S. Army during World War II. He was quickly promoted to first sergeant shortly after enlisting while still stateside. Smith would help lead an infantry company in Europe from 4 October 1944, through occupation duties that lasted until November 1945. Smith grappled with his wartime experiences for the rest of his life. He found solace in writing to his former comrades and journaling short stories of his experiences.

The book’s title originates from one such story based on a brief encounter with a German prisoner of war. Upon realizing the two noncommissioned officers shared the same responsibilities, the captive German called Smith “mother of the company” (p. xi). Smith’s love letters and short stories capture many emotions and experiences shared by the American soldier during World War II and the generations of warriors before and since.

The story is sometimes slow-paced and not as compelling as other action-driven war memoirs. The value of Smith’s volume is the calm, matter-of-fact narrative that recounts fighting understrength in extreme environments, continuous combat, training in combat zones, and care of the soldiers in your organization. As the reader advances through Europe with First Sergeant Smith and Company G, many parallels appear between his war and the modern Army doctrines focused on large-scale combat operations, multidomain operations, soldier readiness, and great power competition’s transition into war.

First Sergeant Smith often speaks about the tactics, abuses, and practices of the German Army as it receded from its European conquests back to its own borders. He exposes the root issues leading to the need for the Geneva Convention while also revealing the ugly realities of civilian and combatant mistreatment, targeting specific populations, and political prisoner atrocities. Smith’s views of atrocities in his era can quickly be connected to modern events like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or the Hamas attack of 7 October 2023, in Israel, as terrorists transcended lawful combat to violent atrocities on a civilian populace.

One of the most compelling aspects of the book is that while Smith’s division is encumbered with large-scale combat operations, the units of his division are still actively training for future operations. In preparing to breach the Siegfried Line, Smith’s company practiced combat maneuvers and hardened troops through hiking for days. This is a critical takeaway for today’s company, battalion, and brigade commanders and their senior enlisted advisors. How do you plan and train while only miles from a powerful enemy army?

Smith describes the sudden shock of the Battle of the Bulge. The demanding physical requirements of “forced marches in driving snow” connect frighteningly close to today’s recruiting shortfalls and the poor physical fitness of America’s youth (p.46). Smith’s experiences reiterate the way Band of Brothers showed the harsh, cold environments of the Ardennes while facing artillery barrages. Beyond the effects of the cold on the men, Smith recounts communication and equipment failure from the weather. As the modern force focuses on building Arctic capabilities and defeating unmanned aerial devices that can penetrate traditional defenses or identify momentary lapses in defense, Smith’s story is a valuable resource for planning Arctic preparedness from a holistic perspective.

Nearly half of the book focuses on the postwar occupation. This section draws the reader’s attention to the relationship between alliances and enemies after combat. Strategic planners can significantly benefit from this section as Smith describes the chaotic relationship between U.S. forces, Russian allies, former German soldiers, and the civilian populace. Stability operations and returning governance to civilian authorities are among the most complex and ill-structured during the phases of conflict. Understanding and anticipating enemy, ally, and other nations’ postwar relations could alleviate those challenges.

Sergeant Major Zach Wriston, USA

El Paso, Texas