This article has been adapted from a paper presented by Kevin Hymel, for the 1997 Annual Meeting of the Society of Military History.

On the afternoon of September 12, 1918, in the midst of a bloody battle between the American Expeditionary Force and the German Army, two American Army officers, a thirty-two year old lieutenant colonel and a thirty-eight year old brigadier general, greeted each other on a small exposed hill. On either side of them, infantry and tanks maneuvered forward to the French town of Essey, a quarter mile to the north. Small arms fire and an occasional artillery burst kept the air alive and dangerous.

The lieutenant colonel sported a Colt .45 pistol with an ivory grip and his engraved initials. A pipe was clenched in his teeth. The brigadier wore a barracks cap and a muffler his mother knitted for him. As they spoke to each other, a German artillery barrage opened up and began marching towards their position. Infantrymen scattered and dove for cover, but the two officers remained standing, coolly talking with each other.

The Lieutenant Colonel, George S. Patton, had been in the Army for nine years, and the Brigadier General, Douglas Mac-Arthur, for fifteen, but the two West Pointers had never met. Their careers had taken them in different directions until this day during the First World War. Both officers became famous for their bravery and daring in the Second World War, yet both set the precedent for courage under fire in the First. That Patton and MacArthur did remain standing while an artillery barrage passed over is historically accepted, but what they said to each other as the shells began to drop remains a point of controversy. Only by examining the various stories that developed out of this chance encounter can some of the myths be eradicated.

Patton arrived in France first, on June 13, 1917. MacArthur arrived later that same month with his division, the 42nd “Rainbow” Division, but was first to see action. After a period of training, the 42nd was called into combat to plug the gaps in the Allied lines. The Germans were making their last bid to take Paris and end the war before larger numbers of American troops arrived. By the time of the St. Mihiel Offensive, MacArthur had been at the front for five months, inspiring troops and moving them forward until the German offensive was spent.

The battle in which Patton and MacArthur were to meet was the first the American Army would fight as a separate army, in its own sector and guided by its own generals. Despite attempts by the British and French to integrate American troops into their own decimated ranks, the American First Army was organized on June 24, 1918. It formed up west of the St. Mihiel salient, a bulge in the Allied lines twenty-five miles wide and fifteen miles deep, which the Germans had occupied for four years. The first test of the American Army was to eliminate the bulge in the line.

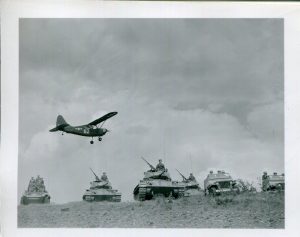

On September 12, beginning at 0100 hours, Allied guns unleashed a five-hour artillery barrage across the salient. Immediately following the bombardment, the doughboys of the 42nd, supported by Patton’s 327th Tank Battalion, started toward their objectives.

MacArthur personally moved forward to maintain control of their units on the battlefield. By 0630, MacArthur was in the Sonnard Woods, 800 yards into enemy territory, where he was pushing forward elements of the 84th Brigade. At about that same time, Patton was advancing his command post to the town of Seicheprey, about 300 yards southwest of MacArthur’s position. With reports coming in that some of his tanks were bogging down on the battlefield, Patton began heading northwest to assess the situation. His reaction to being shelled along the way was: “I admit that I wanted to duck and probably did at first, but soon saw the futility of dodging fate.”

As Patton headed northwest to the town of Essey, MacArthur was making his way north through the Sonnard Woods to the same place. Halfway between the woods and the town, near a farmhouse, Patton spotted MacArthur on a small hill and walked over to him. It was then that the barrage started towards their position, and it was there that they stood, while everyone else ran for cover.

What they said to each other as the barrage approached has been a matter of controversy ever since. The participants themselves give varied accounts; the further from the incident, the more varied, and the incident has also been enriched by imaginary conversations. A careful analysis of the various accounts reveals an unfortunate tendency to accept fictitious accounts without question.

According to Patton’s account, which he wrote four days after the encounter: “I met General MacArthur commanding a brigade, he was walking about too. I joined him and the creeping barrage came along towards us, but it was very thin and not dangerous. I think each one wanted to leave but each hated to say so, so we let it come over us. We stood and talked but neither was much interested in what the other said as we could not get our minds off the shells.” Patton wrote this account as part of a six-page letter to his wife, which, despite all its bombast, managed to be magnanimous to MacArthur’s unwillingness to seek shelter: “I was the only man on the front-line except for General MacArthur who never ducked a shell.”

MacArthur’s version of the story is more convoluted. In his memoirs, Reminiscences, completed forty-seven years after the fact, MacArthur dedicates only two sentences to the story: “We were followed by a squadron of tanks, which soon bogged down in the heavy mud. The squadron was commanded by an old friend, who in another war was to gain world-wide fame, Major George S. Patton.” MacArthur’s memoirs are a bit self-serving and tend to mention everyone’s failings but his own. Thus, it is no surprise that the only thing he mentioned about Patton were his tank problems. He also erred by referring to Patton as a major when he was actually a lieutenant colonel. As for calling Patton his “old friend,” historian Martin Blumenson suggests that the old Army was so small that most officers referred to other officers as ‘friend’ even if they had never met.

The differences in versions do not end there. In 1961, Jack Pearl, a writer of articles, commercials and early television scripts, wrote Blood-and-Guts Patton for the Monarch American Series. According to Pearl, Patton walked up to MacArthur and saluted, but caught himself ducking from a nearby shell. MacArthur then told Patton “Don’t sweat over ’em Colonel. If they’re gonna get you, they’re gonna get you.” When Patton asked him about the situation up ahead, MacArthur offered: “Why don’t you go up ahead and have a look around?” Patton then climbed onto a tank to ride into Essey.

Pearl’s account contains two disputable points. First, there is little proof that Patton caught himself ducking during this encounter since Patton, by his own account, earlier admitted the futility of this action. Second, Patton did not ride a tank into Essey. Once again, by Patton’s own account, he walked into Essey, but he did ride a tank into the next town: “When we got to Pannes some two miles [away] the infantry would not go in so I told the sgt. commanding the tank to go in. He was nervous at being alone so I said I would sit on the roof. I got on top of the tank to hearten the driver. This reassured him and we entered the town.” Even though Pearl seems to quote directly from the two officers, his management of the facts and places seriously calls into question his reliability as a reporter.

Jack Pearl’s initial version of the event was changed later that year by Pearl himself. After completing his book on Patton, Pearl wrote General Douglas MacArthur, again for the Monarch American Series. This time, rather than MacArthur’s comment, “Don’t sweat over ’em Colonel. If they’re gonna get you, they’re gonna get you,” Pearl relates that MacArthur said: “Don’t worry, Colonel, you never hear the one that gets you.” He also elaborated on their conversation: when MacArthur saw Patton was disheartened from the “ribbing” the infantry brass was giving him as his tanks wallowed in the mud, MacArthur offered, “Don’t let them get you down, Colonel. These tanks of yours will dominate the character of war for the next hundred years.” Patton responded, “I’m grateful someone besides me thinks so, sir.” Not only does MacArthur appear paternal toward Patton in this version, he also shows himself to be a great military visionary. In neither version does Pearl cite his sources for the quotes, thereby creating serious doubt in their validity.

Pearl’s “MacArthur” version of the story was next picked up by Jules Archer in 1963. In Archer’s Front-Line General, Douglas MacArthur, Pearl’s story of the Patton-MacArthur meeting was used, but, again, the quotes were not cited. Only the bibliography traces the quotes to Pearl. For some reason, Archer’s use of this quote seemed to legitimize it as author William Manchester later repeated the quotes in American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur, 1880-1964, citing Archer as the source. Manchester goes a step further by calling the chance encounter an inevitable “macho duel” between the two men. Most recently, Geoffrey Parret’s Old Soldier’s Never Die, the latest biography on MacArthur, which intended to correct some of the myths about the general, also fell into the Archer trap. However, D. Clayton James, in his three volume biography on MacArthur, refused to use the exciting but fictitious quotes. Another Patton biographer does hold up a warning flag, questioning the dramatic versions of both Pearl and Archer. Carlo D’Este, author of Patton: A Genius for War, was probably unaware of Archer’s version when he described Manchester’s account as “nonsense.” He may have thought that Manchester actually interviewed MacArthur for his book because D’Este blames the false story on MacArthur’s faulty memory, “with the result that he and his biographer incorrectly identify Patton as a major.”

Whatever was actually said between the two officers was probably remembered by neither. The German shells raining down combined with the other battlefield sounds must have made a deafening amount of noise. While both these men regarded their own personal histories in high esteem, they probably never thought the few words they exchanged on that hill would ever be considered as important.

As the American attack advanced, the Germans began to retreat from Essey. It is not clear from either personal account if Patton and MacArthur walked toward the town together, or moved separately as they passed dead Germans, horses, smashed artillery pieces, and other debris of war. When Patton neared the town, he encountered five tanks reluctant to advance for fear of shelling. Infuriated, he led the tanks into town on foot. Once there the tankers stopped again, refusing to cross the only bridge in town in pursuit of the fleeing Germans, fearful that the bridge was mined. Patton walked across the bridge, proving its safety. Once across, he noticed that there were explosives under the bridge but the wires had been cut.

After recrossing the bridge, Patton returned to the town center just in time to see a group of German soldiers emerge out of a dugout and surrender to MacArthur. MacArthur did not mention this incident in his memoirs but instead reflected on the signs of a panicky German retreat: the musical instruments of a regimental band laid out; a battery of guns left behind still stood their station; and, in a nearby barn, a horse waited in full saddle for a German officer.

Patton approached MacArthur a second time and asked to continue to attack the town of Pannes, two-hundred yards to the north. MacArthur concurred and Patton turned away to lead his tanks to the new objective. MacArthur stayed in Essey, where he helped round up the 100,000 prisoners his unit captured. This marked the last recorded time the two soldiers would ever stand face-to-face exchanging words. Their career paths would take them to very distant places and battlefields, never to meet again.

The second day of the battle was anticlimactic as all of the operation’s objectives had in reality been met by the end of the first day. The next battle for Patton and MacArthur was the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, but they did not serve together in that last campaign of the war.

The dramatic day in September 1918 was significant to both Patton and MacArthur, two young officers in the midst of battle, but the day’s action may have meant more to Patton. It was his first time at war, which would explain his detailed account of the day’s events. MacArthur had already been at the front for five months, so the attack, significant to him for being an all American show, did not hold the same glory that it did for Patton.

The chance first encounter reflected accurately on both men. Patton’s account is straightforward, even if filled with bravado. He brags about his bravery, yet admits his fears. He even gives full credit to MacArthur for sharing his act of bravery. MacArthur’s version is more aloof and clouded in mystery. He seems to enjoy mentioning the sight of Patton’s problems in overcoming the terrain which had bogged down his tanks. He makes a patronizing point by mentioning the tanks were following his infantry. In fact, if MacArthur’s was the only account of the battle, it would seem that tanks had little part in the offensive. MacArthur’s version, so vague in its details, only becomes murkier as later conflicting stories emerged – two, of course, by the same author.

As for Jack Pearl’s report of their exchange in Blood-and-Guts Patton, there is always a chance Pearl interviewed Patton before his death, but it is unlikely. There is no evidence that he served in Patton’s Third Army or as a reporter in Europe. Martin Blumenson, the Third Army’s historian and one of the most respected Patton authors, has no recollection of Pearl’s presence in the European theater. The fact that Pearl himself changes MacArthur’s quotes from one book to the next, within the same year, dissolves the credibility of his tales. That his report of the encounter could become so widely accepted is hard to believe. Apparently, too many researchers were willing to believe the story based on the drama it portrayed.

The chance encounter between Patton and MacArthur is one of those unique scenes of war recorded for history. It is easy to envision these two giants of military history standing among the explosions while all around them, men ran for cover. Unfortunately, exactly what Patton and MacArthur said to each other that day as the German shells rained down will always remain a mystery.