Written By: Lieutenant Colonel Paul Fardink, USA-Ret.

History affords the unique perspective of offering clarity through retrospection. Even though Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood, using mutual respect and negotiation—not bullets and bravado—potentially saved the lives of countless cavalrymen, settlers, Native Americans, and Mexicans by ensuring Geronimo’s surrender in 1886 after years of contentious and bloody Indian wars, he was continually overlooked for promotion and denied a much-deserved Medal of Honor, awarded for personal acts of exceptional courage and valor—literally defined as “strength of mind in regard to danger.” Few would argue that standing face to face on a hot August day in Mexico with a justifiably enraged Geronimo and the son of Cochise took that strength of mind. Nevertheless, when Gatewood achieved a peaceful resolution to years of hard fighting, he displayed an uncommon valor worthy of our nation’s highest honor. The single opponent to his nomination argued that since Gatewood had not come under enemy fire during this event, he was unworthy of the award. However, history should accurately reflect the true impact of this quiet man who changed the face of the Southwest, using words and not weapons.

Born in Woodstock, Virginia, on 6 April 1853 as the oldest son of newspaper editor John Gatewood and his wife Emily, Charles Bare Gatewood had a normal if not exceptional early childhood. This, however, would all change after epochal events in the United States would lead him toward a career in the military. When the Civil War erupted in 1861, eight-year old Charles saw his father march off to fight for the South. When John Gatewood returned, he moved his family to Harrisonburg, Virginia, where he opened a print shop and edited the Commonwealth, a local newspaper. Charles would finish his education there and later briefly teach school before receiving an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy (USMA) at West Point in 1873 from Representative John T. Harris, M.C., of Harrisonburg.

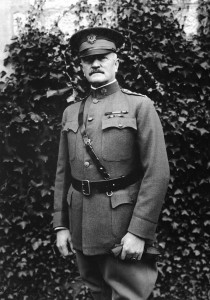

Graduating with the West Point Class of 1877 on 14 June 1877, Gatewood was ranked twenty-third out of a class of seventy-six. The five-foot-eleven-inch Virginian was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 6th U.S. Cavalry. Henry Ossian Flipper, the first black graduate of USMA, was also a member of this class, as well as Thomas Henry Barry, the twenty-seventh Superintendent of USMA (1910-1912). The great majority of this notable class would see duty on the frontier and participation in the Indian Wars, with twenty-six reaching the rank of colonel, five brigadier general, and five major general. Gatewood, however, appeared destined to be overlooked continually for promotion.

By the time Major General George Crook (USMA 1852) assumed command of the Department of Arizona in July 1882, Lieutenant Gatewood had become one of the Army’s premier “Apache men.” He had become familiar with the Arizona Territory and commanded Apache scout units almost constantly since his arrival in the Southwest in January 1878. He had also taken part in the U.S. Army’s campaign against Apache chief Victorio in 1879-80. Gatewood’s life depended upon the scouts under his command accepting and obeying his orders at all times. Crook recognized Gatewood’s detailed knowledge of the Apaches and their customs. Because of this, in 1882, he appointed Gatewood as the military commandant of the White Mountain Indian Reservation, headquartered at Fort Apache, Arizona Territory. Gatewood’s inherent honesty of character, fairness, and respect for Apaches allowed him to excel in this assignment.

Officers who drew Apache duty found it to be very demanding. Patrols often lasted for months. The harsh rigors of living in the field and the continued exposure to extreme weather and inhospitable terrain had consequences. As early as 1881, doctors reported that Gatewood “had rheumatism of knee, ankle, hip and shoulder, the result of exposure in line of duty in Arizona.” Gatewood’s declining health would plague him throughout his career.

On 17 May 1885, Geronimo and Apache Chief Naiche (son of Cochise and the last hereditary Apache chief of the Chokonen, or Chiricahua, tribes) fled the reservation with their band of followers and crossed the border into Mexico. Making periodic raids into the United States as well as in Mexico, they successfully eluded pursuit by both U.S. and Mexican troops. In March 1886, Crook met the warring Apaches at Cañón de los Embudos, Sonora, Mexico, to discuss their surrender. During the talks, Crook threatened and talked down to Geronimo. Although the Apaches surrendered and agreed to return to the United States, Geronimo, Naiche, and some followers feared for their lives and ran one last time on 28 March 1886. Crook resigned his command, and the Army replaced him with Brigadier General Nelson A. Miles. On 13 July 1886, after several attempts to apprehend Geronimo and his band met with failure, Miles asked Gatewood to “find Geronimo and Naiche in Mexico and demand their surrender.”

Displaying incredible skill and bravery, Gatewood and five others followed the Apaches and caught up with them on 25 August 1886 at a bend in the Bavispe River in the Teres Mountains in Mexico. Suddenly, however, the Apaches vanished. Several tense minutes passed before thirty-five or forty Chiricahua Apaches, including many heavily armed warriors, exploded out of the brush. Gatewood did not notice Geronimo among them but welcomed the Apaches cordially, removed his weapons, and passed out tobacco and paper. Everyone rolled cigarettes and smoked.

Geronimo then walked out of the brush and set his Winchester down, greeted Gatewood, and asked about his thinness (Gatewood was ill and extremely frail and gaunt). The two men sat together—too close, Gatewood would later note since he could feel Geronimo’s revolver. For a while they conversed in an English-Apache-Spanish pidgin dialect that allowed them to communicate with interpreters occasionally confirming their statements. When Gatewood delivered Miles’s surrender message, Geronimo wanted to know the terms. Gatewood replied, “Unconditional surrender!” The Apaches would be sent to Florida, where they would await President Grover Cleveland’s decision on their lives. Gatewood concluded by adding, “Accept these terms or fight it out to the bitter end.”

An angry Geronimo stared at Gatewood. After talking about a few other less profound issues, he spoke of all the bad that both countries, the United States and Mexico, had done to his people. Warrior tempers erupted, and the group of Apaches moved away from Gatewood so they could discuss the possible surrender. An hour later, they returned with Geronimo demanding terms similar to those offered in the past: “Take us to the reservation or fight.” Gatewood, however, could not do this. The atmosphere again turned tense, but before anything happened, Chief Naiche spoke up, saying Gatewood would not be harmed.

Breathing easier, Gatewood gambled and said that the remaining Chiricahuas in Arizona had been sent to Florida. Although untrue, he knew it would happen. An irate Geronimo and the Apaches spoke again between themselves. Nothing changed—they demanded a return to the reservation or they would fight. Danger loomed, but Gatewood kept his composure. Eventually Geronimo asked Gatewood what he would do. When Gatewood replied that he would accept Miles’s terms, Geronimo said he would announce their decision in the morning.

The next day, after Geronimo and Naiche agreed to return to the United States, Gatewood, realizing that his knowledge of the Apaches—especially the White Mountain Apaches—was unique, wrote a letter to his wife declaring that it was time for him to begin working on a memoir. Because of this, not only did he record Apache oral history before it became known as “oral history,” he documented arguably one of the most spectacular feats of the Indian Wars—meeting Naiche and Geronimo in Sonora, Mexico, talking them into surrendering, and getting them safely back to the States even though some within the Mexican and U.S. Armies wanted the famed Apache leaders dead.

As 1886 ended, Gatewood’s health once again began to fail. He had never recovered from the hardships suffered while in Mexico and the southwestern United States. As a result, the Army granted him an extended leave of absence. In May 1887, he returned to Miles’s headquarters (then in Los Angeles), where he served as aide-de-camp. In the fall of 1890, he re-joined the 6th U.S. Cavalry and was assigned to H Troop.

On 18 May 1892, a band of small ranchers and rustlers became enraged at the gunmen hired by the larger rancher owners in Johnson County, Wyoming. They set fire to the buildings at Fort McKinney, Wyoming, where the Army had confined a local cattle baron’s hired killers. The fire spread, threatening to destroy the entire post. Gatewood joined a small group of volunteers as they hurriedly placed cans of gunpowder in the burning buildings. The plan was to blow up the structures already engulfed in flames to save the remaining buildings. Suddenly, some burning rafters parted, fell, and prematurely detonated a can of powder. Gatewood was blown violently against the side of a building and badly injured.

Gatewood took a physical examination at Fort Custer, Montana, on 3 October 1892, with the following diagnosis: “Lieutenant Gatewood has suffered intermittently with articular rheumatism during the past twelve years. At present it exists in a sub acute form, and affects chiefly the right shoulder and hip. When combined with his injury from the explosion, which rendered his left arm almost completely disabled, the result was a foregone conclusion: Permanently disqualified physically to perform the duties of a captain of cavalry, and that his disability occurred in the line of duty.” Gatewood expected to be retired from the service but instead found himself remaining on the active duty roles as a member of the 6th Cavalry. Nevertheless, he was often on extended leaves of absence as the rapid deterioration of his health continued.

On 2 May 1895, Captain Augustus P. Blocksom recommended Lieutenant Gatewood for the Medal of Honor. It was endorsed by the commanding officer of the 6th Cavalry, Colonel D.B. Gordon, and the Commanding General of the Army, General Nelson A. Miles, but disapproved by Joseph B. Doe, Acting Secretary of War, on 24 June 1895 because Gatewood did not come under hostile fire during his pursuit of Geronimo and his band of Apaches. Gatewood had displayed extreme bravery. His services were extensive and, in fact, indispensable. Nevertheless, four Medals of Honor had been given to others during the efforts to capture Geronimo, but not to the one man instrumental in achieving the surrender.

The news greatly disappointed Gatewood. He spent the last year of his life nursing his ill health. The Army did, however, allow him to remain on the payroll instead of forcing him to retire. His health, however, continued to deteriorate, and he entered the hospital at Fort Monroe, Virginia, on 11 May 1896. On 20 May, he died from a malignant tumor in his liver. At the time of his death, he was forty-three years old and the senior lieutenant of his regiment, having never achieved the rank of captain after nineteen years service. Gatewood’s wife, Georgia, did not have enough money to bury her husband, so the Army arranged for burial in Arlington National Cemetery. Georgia survived the next twenty-four years on a pension of $17 a month she received from the government. She eventually moved to California to live with her son, “Charlie Junior,” born on 4 January 1883, at Fort Apache, Arizona Territory.

Charles B. Gatewood, Jr., was thirteen years old when his father died in 1896. He would later graduate from West Point with the Class of 1906 and retire as a colonel after thirty years service. Charles, Jr., launched a lifelong crusade to establish as record his father’s impact on the history of the Indian Wars. His fastidious and continuous effort to document his father’s participation in the last Apache war is now housed at the Arizona Historical Society in Tucson. Lieutenant Gatewood’s son laid the groundwork for authors such as Louis Kraft (quoted extensively in the second half of this article) to discover his father’s life and contributions.

The words of Major General Augustus Perry Blocksom, Gatewood’s West Point classmate who served as a lieutenant with Gatewood in the 6th Cavalry and also commanded Indian scouts, aptly captured the character of Charles Gatewood. Blocksom wrote Gatewood’s obituary for the annual reunion of the USMA Association of Graduates in 1896 which states: “His life was simple and unassuming. He suffered many hardships, but his kind heart, genial humor, and gentle manners always gave evidence that nature had created him a true gentleman. His work was done in a comparatively limited field, and was unknown to and therefore unappreciated by the vast majority of our people; but to us who knew him and his deeds so well, it seems hard that he should have received no just reward for his services. His name is still on the lips of the people of Arizona and New Mexico, and will not soon be forgotten by his comrades in the Indian campaigns.”

One might wonder how such an instrumental figure in America’s westward expansion such as Lieutenant Charles Gatewood could have escaped acclaim and, at minimum, placement in archives of those most interested in the all-important period of our country’s history following the Civil War. Thanks to Gatewood’s own proclivity for language and his desire to record the oral history of the Apaches—not to mention the dedication of his son, Charles, Jr., to preserving the legacy of his late father—future writers of note, such as acclaimed author and historian Louis Kraft, would become interested in the life of Lieutenant Gatewood, whose story attracts compassion and spurs that uniquely American desire to help the underdog—or those apparently treated unfairly—in the annals of history.

In a recent discussion with Kraft, much of the background surrounding the “Gatewood Enigma” became clear. To be sure, it is a story rife jealously and ambition—none of which appear to have emanated from Gatewood himself but from those close to him and envious of his accomplishments. Fortunately, Gatewood’s memories of the Apaches are as special as his achievements, as evident in a number of chapters he drafted for a book he planned to complete. Sadly, his premature death at age forty-three prevented him from finishing the project. Kraft generously offered to discuss how his personal interest in Gatewood turned into a quest to set the record straight.

Just before Kraft’s first book on the Apache Wars, Gatewood & Geronimo (University of New Mexico Press, 2000), moved toward publication, he realized how much of Gatewood’s experiences among the Apaches would not be told because of page limitations. Gatewood’s words would then remain in obscurity for another year until Kraft decided to contact the Arizona Historical Society to ask for permission to compile Gatewood’s notes into a readable manuscript. He then pieced together and edited the lieutenant’s writing, which became Lt. Charles Gatewood & His Apache Wars Memoir (University of Nebraska Press, 2005), resulting in a major reference for both researchers and historians. Kraft has also written extensively about cavalry operations in the American West, including a book on George Armstrong Custer. Few author/historians are as qualified as Kraft to assess the level of bravery inherent in Gatewood’s actions when confronting Geronimo.

Kraft further explained how his interest in Gatewood first occurred, an interest which has grown and been reinforced by others over the years. “My initial visit to the Gatewood Collection at the Arizona Historical Society in Tucson spurred my interest and encouraged what has become a passion. I didn’t know anything about Charles Gatewood and never thought I would write about him. However, when I stumbled upon him I was floored.” Kraft continued, “The history of the Indian Wars had relegated him to a minor character—read, he served his country, period. Perhaps Generals Miles and Crook (especially Miles) are responsible for this—it is shocking that Gatewood never rose above lieutenant when almost every other officer serving in Mexico in 1886 retired or died a colonel or general. There are superstars in the West (Custer, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Geronimo, Earp, Holliday, Cody, Hickok, Crockett, Carson to name a few) and then there are major players (Crook, Miles, Roman Nose, Black Kettle, Naiche, Ned Wynkoop, Chivington again to name a few—this list is much longer). Telling Gatewood’s story was almost heresy. The plus is that now Gatewood is a player and will someday appear in documentaries. Hopefully others will learn more about him and put their findings to words; for even though he was only a lieutenant, he played a major role in the last Apache war—and even more so if one considers his stand for human rights.” Kraft further added, “Gatewood was slender, tall, and at times struggled with his health. The Apaches called him ‘Bay-chen-daysen,’ which means big nose. Contemporaries considered him quiet, cool, courageous, intolerant of injustice, and honest, but the trait that best served him was his ability to accept and treat fairly the Apaches he commanded and oversaw on the White Mountain Indian Reservation.”

Kraft continued: “Perhaps the most unusual aspect of the valor of Lieutenant Gatewood on that day with Geronimo was that far from a brash bit of bravado his actions were rather an intelligent display of an incredible understanding of his foe. Yet, the essential question sustains: Why did he succeed when a force of 5,000 cavalrymen had failed?” For Kraft, it came down to the fact that “First, American and Mexican troops intended to hunt down and kill the Apaches, and the Indians knew this. Gatewood, who they knew, entered their camp with three interpreters, an Apache scout who was related to band members, and maybe one soldier. He did not come to kill, and the story he told of the removal of their people in Arizona to Florida, even if it had not happened yet, sounded true. This would give them nothing to return to if they re-crossed the border. Also, they knew that it was a matter of time before other soldiers caught and killed them.” Kraft contends that Gatewood offered Geronimo and the Apaches “the best deal they could possibly get—return to the United States, exile to a place called Florida where they would be reunited with the rest of their people, and the promise to return to their homeland sometime in the future. Gatewood offered them a chance to live, and they took it.”

As for Gatewood’s lack of fame, Kraft stated that “people wonder why history has forgotten this man. General Nelson Miles is the major culprit here, as he did everything possible to ensure that his command, the 4th U.S. Cavalry, got all the credit for the capture of Geronimo and the last of the warring Apaches—about thirty-eight people, including warriors, women, and children. Gatewood belonged to the 6th U.S. Cavalry, Crook’s regiment at the time. Crook had previously turned his back on Gatewood when the lieutenant refused to drop charges against a territorial judge for defrauding the White Mountain Apaches and had no intention of supporting Gatewood when Miles attempted to remove his name from the surrender of the Apaches.

“After the surrender of Geronimo, Gatewood would become an aide-de-camp to General Miles but always seemed to remain an outsider and few understand why,” said Kraft. “Again, Miles wanted all the glory to go to the 4th Cavalry. Ridiculous as it sounds, Gatewood was known as a ‘Crook man.’ In November 1887, a year after the Apaches surrendered, Tucson, Arizona Territory, hosted a festival to honor Miles and the 4th Cavalry at the San Xavier Hotel. The general made certain that the ‘Crook man’ did not attend by ordering him to remain at headquarters, which further distanced the lieutenant from the events that ended the war. At the celebration, when Miles was asked about Gatewood’s participation in the surrender, Miles stated that he ‘was sick of this adulation of Lieutenant Gatewood, who only did his duty.’”

Kraft added that “During the celebration, when Gatewood realized that some of Miles’ servants were on the Army’s payroll, he refused to sign the order for them to be paid as ‘bearers,’ as it was against military regulations. If we can believe Gatewood’s wife, Georgia, this angered Miles, who looked for ways to court-martial her husband. Gatewood was a first lieutenant and Miles’s officers were lieutenants or captains during the hunt for Geronimo that summer and fall of 1886. Nevertheless, all Miles’s officers retired or died with the rank of colonel or general, while Gatewood was still a first lieutenant at the time of his death, next in line via the seniority rule to become a captain. The military even refused to award Gatewood the Medal of Honor for his extraordinary feat, as it was not performed during the heat of battle.” Kraft further added, “In my humble opinion this was a sad statement about U.S. Army values.”

The 1993 movie, Geronimo: An American Legend, which featured Gatewood as a central character (played by Jason Patric), brought his name to an unaware American public, even though the film was filled with inaccuracies. Kraft said the movie was actually his introduction to the lieutenant as well and added, “Britton Davis (played by Matt Damon), a lifelong friend of Gatewood was just out of West Point when Geronimo (Wes Studi) crossed the border in 1884 to be escorted back to the reservation by Gatewood (who did not perform this duty—Davis did). It was not until I began researching the books that I realized that although the film pretends to be factual, it is fiction from the beginning to end.” Kraft stated that it mixes up events and dates, and often places characters in events in which they never participated. “Geronimo never made a great shot to scare off a posse. At the time of the film, Gatewood rode a mule, commanded Apache scouts and not troopers, and never killed an Apache warrior in one-on-one combat,” said Kraft. “Also, he never tracked the recalcitrant Apaches with Chatto (Steve Reevis) and Al Sieber (Robert Duvall). There was no shootout with scalp hunters in a cantina, Davis was not with Gatewood in 1886, and the lieutenant was not hit or harmed when he met the Apaches and talked them into returning to the United States. The errors are endless.”

Kraft continued to discuss additional inaccuracies, saying, “Actually Lieutenant Britton Davis resigned his commission in 1885, which did not become official until 1886, and later wrote The Truth About Geronimo (Yale University Press, 1929). Davis wrote this about Gatewood: ‘Cool, quiet, courageous; firm when convinced of right but intolerant of wrong; with a thorough knowledge of Apache character.” Davis was a good soldier and a fair administrator of the Apaches at Turkey Creek, a forested area east of Fort Apache. His compassion for the Apaches, along with the rough excursion he survived in Mexico in 1885, contributed to his disillusionment with the Army, the U.S.’s treatment of the Apaches, and his decision to resign his commission. The fact that Gatewood did not totally fade into oblivion is in large part due to Lieutenant Davis and his book.”

In discussing Geronimo, Kraft said, “While Geronimo would live a long life, dying while still incarcerated in 1909, he was never permitted to return to his native lands despite pleas to President Theodore Roosevelt. Geronimo recounted his life to S. M. Barrett, who assembled it as Geronimo: His Own Story (reprinted by E.P. Dutton in 1970).” Still many historians still ponder why Geronimo trusted Lieutenant Gatewood—or if he ever regretted that later in life. Kraft stated he believes that “by the summer of 1886 Gatewood’s fair handling of the White Mountain Indian reservation and his ability to deal with Apache scouts in the field were well known to the Apaches. They knew that Gatewood did not lie and would buck the military if he thought the Apaches had been wronged. There were not many white men who would do this. Daklugie, Chief Juh’s (pronounced ‘Who’) son translated Geronimo’s words for Barrett and said that Geronimo regretted trusting Miles, who had lied to him. But he never blamed Gatewood for the general’s perfidy.”

In the conclusion of his commentary, Kraft expressed hope for continued attention for Gatewood “…whose actions during his entire tenure with the Apaches were exemplary. He quickly viewed them as human beings who should be treated as such. Gatewood was a most special man, and more historical papers such as this will encourage sustained and justified interest in his life. One must remember that during the Indian Wars there weren’t many white men on the frontier who would put their careers at risk and stand up for a people whose entire way of life was coming to an end, as the citizens of the United States carved their new land.”