By Lieutenant Colonel Ronald W. Johnson, USA-Ret.

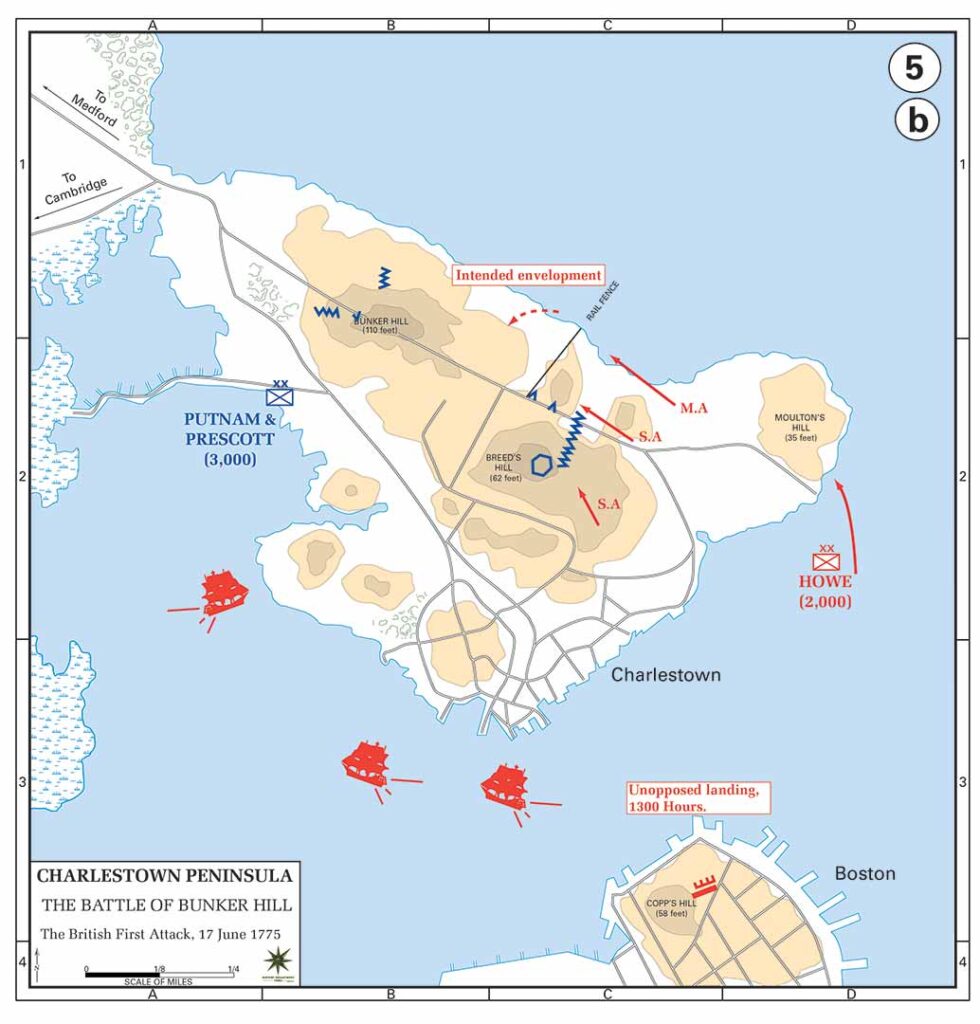

When the British troops occupying the city of Boston awoke on 17 June 1775, they were shocked to see that the Americans had built a redoubt on Breed’s Hill across the bay from the city overnight. In response, British Major General Sir William Howe, a master of light infantry tactics, planned to attack the American position with two divisions, one against the redoubt on the Americans’ right and the other against breastworks on the Americans’ left. His main attack would be a flying column of light infantry around that left flank. He could tell it was vulnerable.

British General Thomas Gage, Commander-in-Chief, North America, watched the troop employment from Boston and said that “if one John Stark was with them, they would fight; for he was a brave fellow.” Colonel John Stark was indeed with the Americans, and, like Howe, he recognized the left flank was a huge vulnerability. He was about to ruin Howe’s day.

John Stark was born on 28 August 1728 and grew up in what is now Manchester, New Hampshire. He hunted, fished, and became well-known for his marksmanship. Learning to survive and be self-sufficient in harsh environments instilled a boldness and confidence that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

On 28 April 1752, Abenaki warriors captured Stark while he was on a hunting and trapping expedition along the Baker River. The Indians forced every captive to participate in a ceremony called “running the gauntlet.” The warriors formed up in two lines, armed with a stick or club with which they hit the captive as he ran through. Stark, however, grabbed his own pole and hit back, earning the respect of the tribal leaders in the village. He was dubbed “Young Chief,” and he was treated kindly until ransomed after five weeks in captivity.

During the French and Indian War, Stark served as an officer in Major Robert Rogers’ Rangers, a legendary provincial military unit and the precursor to today’s U.S. Army Rangers. Rogers’ Rangers were renowned for scouting, intelligence gathering, and raids; both the French and Indians feared them and were awed by their achievements. Ironically, William Howe’s oldest brother, George, went on patrol with Rogers’ Rangers to learn wilderness fighting. It is likely George Howe and John Stark were on the same side of the battlefield when Howe was killed near Fort Ticonderoga on 5 July 1758, nearly seventeen years before Stark and William Howe were to be on opposite sides on Breed’s Hill.

precursor to the modern U.S. Army Rangers, during the French and Indian War.

Rogers’ Rangers were renowned for scouting, intelligence gathering, and raids and they were feared by French and Indian forces. (To Range the Woods: New York, 1760, by Specialist 4 Manuel B. Ablaza, U.S. Army Museum Enterprise Art Collection)

In March 1757, then-Captain Stark was in command of a ranger detachment at Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George, New York, when the French launched a surprise night attack. The assault appeared to be going well, but only because Stark ordered his men to hold fire until the French reached the top of their ladders. The attackers failed to capture the fort, and Stark would employ the same tactic to great success on Breed’s Hill.

Eighteen years later, in April 1775, when the news of bloodshed at Lexington and Concord arrived in New Hampshire, Stark was at work in his sawmill at his farm. He immediately retrieved his musket and ammunition from his house, mounted his horse, and rode to join the fight without pausing to change clothes. Volunteers joined him as he rode; eventually, he enlisted almost 800 men, organized into twelve companies. The 1st New Hampshire Regiment would be the largest regiment facing the British outside Boston.

American left and repelled the British attack on their position with heavy casualties. (Department of History, U.S.

Military Academy)

On 17 June 1775, Stark’s regiment was ordered to join American forces on Breed’s Hill in what is now known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. The march required crossing a narrow isthmus, about thirty feet wide, from the mainland onto the Charlestown Peninsula. The British were raking the isthmus with cannon fire from their ships in the Charles River, but Stark led his regiment at a methodical pace. Captain Henry Dearborn (later Secretary of War under President Thomas Jefferson) suggested Stark pick up the pace, given the enemy fire. According to Dearborn, “With a look peculiar to himself, he [Stark] fixed his eyes on me and observed, with great composure, ‘Dearborn, one fresh man in action is worth ten fatigued ones’ and continued to advance in the same cool collected manner.”

Stark quickly saw the open left flank in the American lines, between a rail fence and the beach next to the Mystic River. “It was a way so clear that the enemy could not miss it,” Stark later said. Indeed, Howe had not missed it.

Stark immediately moved to fill the gap. Most of his regiment manned the rail fence, stuffing it with hay and grass to create the illusion of a solid barrier; another sixty men clambered down the eight-foot bank to the beach to build a low wall with stones. Stark thrust a stick into the sand about eighty yards in front of the stone wall and ordered, “Don’t a man fire till the redcoats come up to that stick. If he does, I’ll knock him down.” Stark wanted to fire at close range just as he did at Fort William Henry.

Eleven companies of British light infantry, comprising over three hundred men, squeezed onto the beach, four or five across. It was exactly as Stark had anticipated. Stark’s men were in three ranks, employing “continuous fire,” a tactic developed by Rogers’ Rangers. With the first rank kneeling, the second rank stooping, and the third rank standing, each rank fired a volley in turn. They used their traditional “buck and ball” ammunition (four buckshot to every musket ball), which made every shot more effective. Howe’s light infantry paid the price once Stark’s men opened fire; when the redcoats turned and ran, they left ninety-six of their comrades lying on the sand. All the British casualties were between the stick and the wall, showing how Stark’s troops coolly obeyed his orders.

Since his main attack had failed, Howe was forced to use frontal attacks against the redoubt, breastwork, and rail fence. The first two attacks were extremely costly, and the British fell back. Howe changed tactics on the third attack, veering away from Stark’s troops behind the rail fence to concentrate on the redoubt. The Americans in the redoubt fought bravely but ran out of ammunition and were forced to bolt to the rear.

Stark gathered his men for an orderly, rearguard action that would slow the enemy’s advance and allow many of the Americans to evacuate the redoubt and cross the narrow isthmus to the mainland. Most of the friendly casualties would be suffered during the retreat from the redoubt, but the outcome would have been much worse if Stark’s regiment had not remained to slow down the British. “The retreat was no flight,” British Major General John Burgoyne, who watched the battle from Boston, would write. “It was even covered with bravery and military skill.” Stark’s regiment was the last American unit to leave the battlefield.

The British won the battle but lost 1,054 men (226 killed, 828 wounded), almost fifty percent of their entire force in the battle. The loss of officers (ninety-two out of approximately 250) was particularly painful. The American casualties were also heavy, with 140 dead, 271 wounded, and thirty captured.

Stark’s regiment remained as part of the army besieging Boston under the command of General George Washington. The stalemate persisted until the British were compelled to negotiate a truce after Henry Knox arrived with captured artillery from Fort Ticonderoga in March 1776. The British agreed to depart in ten days; when the deadline passed with the redcoats still in the city, Washington prepared to attack. Stark was entrusted with the key role of crossing the water to attack the British artillery on Copp’s Hill, but when Stark’s men began to descend to the wharf, the British ships began to sail.

After his ignominious retreat from New York City across New Jersey and into Pennsylvania during the summer and fall of 1776, Washington’s bold Christmas Day attack through a raging storm on the Hessian outpost in Trenton, New Jersey, revived American spirits. Stark was in the thick of the action during the battle. Washington’s main attack was from two directions, with Major General Nathanael Greene advancing from the north and Major General John Sullivan attacking from the south.

Stark had served under Sullivan, a fellow New Hampshirite, since the Siege of Boston. Stark’s regiment was Sullivan’s advance guard at Trenton. Stark led it in a “thundering charge” toward one of the Hessian regiments and “dealt death wherever he encountered resistance, and broke down all opposition before him,” according to a firsthand account of the battle. Stark had trained his regiment to use bayonets, and the Hessians were shocked to see Americans running at them through the storm with cold steel.

The American victory was absolute. Twenty-two Hessians were killed, eighty-nine were wounded, and eight hundred ninety-six were captured. Washington’s forces suffered only a handful of casualties.

The British strategy for 1777 included an invasion by Major General John Burgoyne from Canada to cut off the northern colonies from the rest of America. Vermont, in Burgoyne’s path, requested assistance from neighboring colonies, and New Hampshire answered the call. The name of John Stark again attracted potential fighters, and nearly 1,500 men now followed him to Vermont.

As Burgoyne advanced, his lengthening line of communication strained his logistics to the breaking point. On 17 August, he dispatched a Hessian force to capture supplies in Bennington, Vermont, and gather horses from the countryside. Stark was waiting.

Stark pointed at the enemy lines and told his troops “Tonight the American flag floats from yonder hill, or Mollie Stark sleeps a widow.” He then launched a three-pronged attack—a frontal attack and around both flanks—that overwhelmed the Hessian troops and, subsequently, the reinforcements sent to their aid. The defeat not only weakened Burgoyne’s force but deprived him of necessary supplies.

march to join Major General Horatio Gates on 18-19 September. (Department of History, U.S. Army Center of

Military History)

Stark’s victory at Bennington set Burgoyne up for failure in the Saratoga Campaign, with defeats at Freeman’s Farm on 19 September and Bemis Heights on 7 October. The British were severely punished without reaching the American lines in both battles. Burgoyne withdrew and the Americans followed. By 11 October, the British were virtually surrounded.

Stark, who was operating as an independent command, crossed the Hudson River with his men on small rafts on the evening of 11 October and sealed off Burgoyne’s final escape route. Stark’s regiment took up positions on terrain now called Stark’s Knob. With supplies dwindling and no chance of escape, Burgoyne surrendered his army on 19 October.

(The Battle of Bennington, August 16, 1777, by Alonzo Chappel, Bennington Museum)

Saratoga was the turning point of the Revolutionary War. It was the first defeat of a major British force and swayed the French into joining the conflict on the American side.

In recognition for his performance during the Saratoga Campaign, Stark received a commission as a brigadier general in the Continental Army in December 1777. He served as commander of the Continental Army’s Northern Department twice (1778 and 1781). In September 1780, he was one of thirteen general officers to sit on a military tribunal to pass judgment on British Major John André, the intelligence officer who facilitated Major General Benedict Arnold’s betrayal of the United States.

Stark went back to his farm when the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War was signed in 1783. He named his horse “Hessian,” presumably a tongue-in-cheek reference to his successes against the Hessians at Trenton and Bennington. Three years later, he was appointed major general by the Continental Congress by brevet.

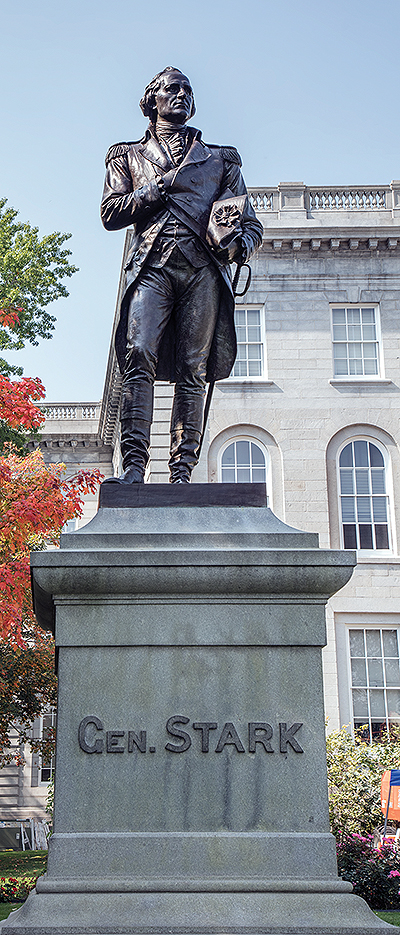

When Stark died on 8 May 1822, at the age of ninety-three, only two other Revolutionary War generals (Thomas Sumter of South Carolina and the Marquis de Lafayette) were still living. The State of New Hampshire donated a bronze statue of Stark to the National Statuary Hall Collection at the U.S. Capitol in 1894, where it remains today. The official New Hampshire state motto, “Live Free or Die,” is a quote from Stark in a letter to veterans of the Battle of Bennington.

the Capitol grounds of Concord, New Hampshire. (Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Washington and Greene were superb strategists. They recognized the Revolution remained valid as long as the Continental Army was in the field; their genius was their ability to keep it intact whether they won or, more often, when they lost battles. The Americans arguably won outright only four battles in the War for Independence: Trenton/Princeton, Saratoga, Cowpens, and Yorktown. It is noteworthy that Stark had key roles in two of those battles in addition to the shellacking administered to the British at Bunker Hill. Stark was a true American hero and one of the important, if somewhat overlooked, figures of the Continental Army.

About the Author:

Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Johnson, USA-Ret, was commissioned in 1977 as a Field Artillery officer through the ROTC program at the University of Arkansas, where he majored in Journalism. He served twenty-one years in Alaska, Korea, Germany, Oklahoma, and the Pentagon. His final assignment was chief of the Materiel Requirements Division, Directorate of Combat Developments, U.S. Army Field Artillery School, Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Currently, he is a docent at the National Museum of the United States Army, Fort Belvoir, Virginia. He is a past president of the Second Region of the Association of the U.S. Army.