By A.J. Orlikoff, Interim Executive Director, Historic Congressional Cemetery

On 20 July 1807, congressmen, department heads, military officers, and others gathered at a small, 4.5-acre cemetery in Square 1115 of Washington City, the fledgling capital of the new nation. Overlooking the banks of the Anacostia River, the burial ground had no official name and only a few months earlier had welcomed its first permanent resident—William Swinton, a stonecutter working on the U.S. Capitol. The assembly stood in full ceremony as Senator Uriah Tracy of Connecticut was laid to rest.[1] Because the journey to his home state was too long and arduous by carriage, the burial had been hastily organized out of necessity. Elected to Congress in 1796 and president pro tempore of the Senate in the Sixth Congress, Tracy had also served in the militia at the Battles of Lexington and Concord with the Roxbury Company during the Revolutionary War.[2] No one in attendance realized that Tracy’s burial marked the official beginning of America’s first burial ground of national memory—Historic Congressional Cemetery.

The story of Congressional Cemetery is characterized by national history, community ties, and patriotic memory. Its evolution—predating Arlington National Cemetery by decades—forms a microcosm of American remembrance, a landscape of history curated by Americans who lived it, and their legacies remain very much alive today. Congressional Cemetery is a community cornerstone, visited by tens of thousands of people each year. Whether they come as members of the popular K9 Corps, history enthusiasts, or casual tourists, all find meaning within its gates.

Founded in 1807, the parcel on Square 1115 was purchased by eight prominent citizens, including Commodore Thomas Tingey, first commandant of the Washington Navy Yard. All were parishioners of Christ Church, Washington Parish, and in 1812 they ceded the cemetery to the vestry, which named it Washington Parish Burial Ground.[3] Christ Church remains the sole owner, and in 1976 the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery was formed to operate the site on the church’s behalf.

Despite its official name, few Washingtonians used it. After Tracy’s interment, congressional and federal leaders saw the cemetery’s convenient location and pleasing aesthetic as ideal for an unofficial national burial ground. Soon, other members of Congress followed Tracy in death, and they too were laid to rest here. By the 1820s, congressional and federal interments numbered in the dozens, and the site became known as Congressional Cemetery—or, as travel writer Jonathan Elliot called it in 1830, “The National Burying Ground.”[4]

By 1815, Congress sought to commemorate its deceased members more formally, commissioning famed architect Benjamin Latrobe to design monuments. The resulting sandstone cenotaphs, financed by Congress, were placed at grave sites; later, cenotaphs were erected even when a member’s remains lay elsewhere. The practice continued until 1876, ending as tastes changed, prompting Senator George Hoar of Massachusetts to quip that the sight of them was “a new terror to death.”[5]

With its congressional connection firmly established, the cemetery became the nation’s premier burial ground of memory, attracting Americans from all walks of life. Today roughly 70,000 individuals are interred or inurned within its thirty-five acres. More than 20,000 memorial stones dot the rolling landscape, each representing an individual or family legacy.

Some notable interred residents include Vice President Elbridge Gerry, the only signer of the Declaration of Independence buried in Washington, DC; John Philip Sousa, director of the Marine Band and prolific composer; Belva Lockwood, the first woman to run for president; Mathew Brady, pioneering photographer and photojournalist; J. Edgar Hoover, first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and Alain Locke, Harlem Renaissance philosopher and the first African American Rhodes Scholar.

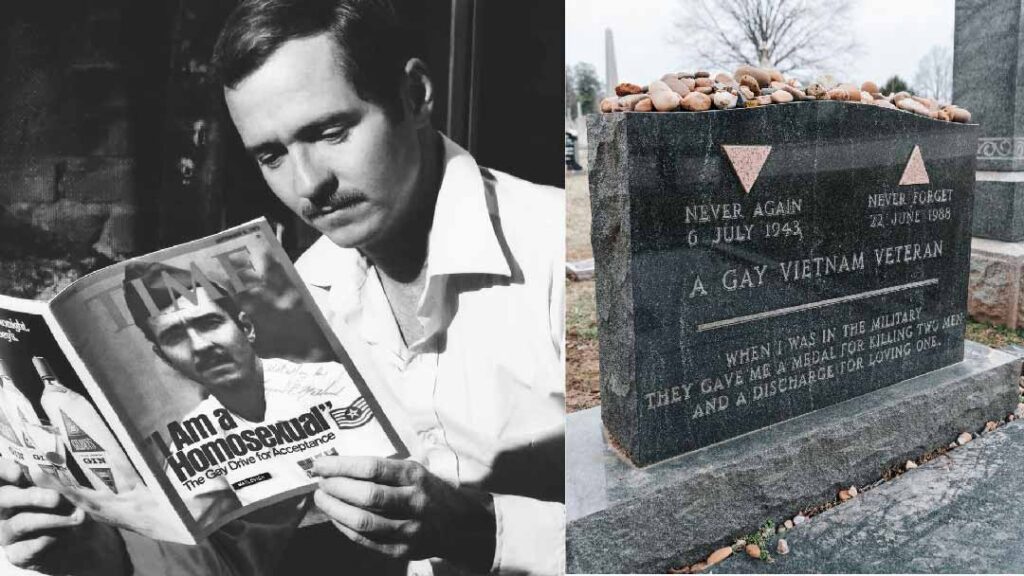

The cemetery is also the final resting place of more than 1,500 veterans of America’s major conflicts. Among them are two commanding generals of the U.S. Army—Major Generals Jacob Jennings Brown and Alexander Macomb—both War of 1812 heroes awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.[6] Other military notables include Colonel Archibald Henderson, longest-serving commandant of the Marine Corps; Commodore Thomas Tingey, first commandant of the Washington Navy Yard; Commodore John Rodgers, a flag officer of the Barbary Wars and War of 1812; Brigadier General Pushmataha, Choctaw war chief and American ally; Almira Brown, the first woman to serve at the Washington Navy Yard; and Technical Sergeant Leonard Matlovich, who challenged the Air Force’s ban on gay service members and became the first named gay person to appear on the cover of a major U.S. magazine.[7]

Today, Congressional Cemetery remains committed to honoring those in its care through community engagement, education, environmental stewardship, and historic preservation. Like many historic cemeteries, it is transforming burial grounds from places devoted solely to grief into spaces that celebrate life. In 2024 alone, the cemetery offered more than 200 public programs, welcoming tens of thousands of guests. Activities range from docent-led walking tours and a Cemetery Speaker Series to “Cinematery” summer movie nights and “Soul Strolls,” an immersive outdoor theater experience featuring actors portraying interred residents. In addition, there are hundreds of members of the Congressional Cemetery K9 Corps. Dogs, with their humans, breathe life into the historical grounds, as the happy wagging tails of dogs in the cemetery mark a new chapter in the cemetery’s story.

From the first hastily arranged funerals overlooking the banks of the Anacostia to the bustling hub of history, culture, and community it is today, Historic Congressional Cemetery has traced—and helped shape—the evolving story of the nation it serves. Its cenotaph-lined paths and weathered headstones enshrine the memories of statesmen, soldiers, trailblazers, and everyday Washingtonians, while its lively slate of tours, lectures, films, and festivals ensures their legacies speak to new generations. At Congressional, death and life meet in dynamic conversation: every program, every visitor, every cherry-blossom stroll adds fresh chapters to a 218-year narrative of public service and civic pride. As Congressional Cemetery continues to honor the past and innovate for the future, it stands as a testament to the idea that a burial ground can be a living monument: rooted in remembrance, flourishing in community, and ever ready to inspire the next story etched into its sacred ground.

Making a Visit:

Historic Congressional Cemetery is located at 1801 E. Street, SE, in Washington, DC. The cemetery is open for self-guided tours during daylight hours; free, docent-led tours are held every Saturday from April through October at 1100, beginning at the front gate of the cemetery, and other special tours and programs are held throughout the year. For more information on Historic Congressional Cemetery, visit https://congressionalcemetery.org.

[1] The National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), 22 July 1807.

[2] Selden Marvin Ely, “The District of Columbia in the American Revolution and Patriots of the Revolutionary Period Who Are Interred in the District or in Arlington,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society 21 (1908): 128–54.

[3] Abby Arthur Johnson and Ronald Maberry Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol: Congressional Cemetery and the Memory of the Nation (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2012), 14–17.

[4] Ibid, 51.

[5]United States Senate, “First Senator Buried in Congressional Cemetery,” Art & History (website), accessed June 11, 2025, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/First_Senator_Buried_in_Congressional_Cemetery.htm.

[6] Army Historical Foundation, “Major General Alexander Macomb,” On Point (website), accessed 12 June 2025, https://armyhistory.org/major-general-alexander-macomb/.

[7] Tessa Berenson, “The Air-Force Veteran Who Fought the Gay Ban 40 Years Ago,” Time, 16 September 2015, accessed 12 June 2025, https://time.com/4019076/40-years-leonard-matlovich/.