By Terrance McGovern

Fort Grant and Fort Amador were U.S. Army posts built to protect the Pacific (southern) end of the Panama Canal from naval attack. Initially, Fort Grant consisted of both the Balboa Dump (a mangrove swamp filled with spoil from the Panama Canal’s Gaillard Cut) and a series of islands lying just offshore, some of which were connected by a causeway to the Balboa Dump. Fort Grant and Fort Amador were designated by the War Department G.O. No 153 (25 November 1911) as a single military reservation. The defenses of Fort Grant were constructed between 1914 and 1917 as the principal Coast Artillery Corps fortification for defending the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal. The military reservation included a number of large artillery batteries on the various islands, as well as a controlled mine complex, while initially quarters for eight companies of coast artillery were built on the former Balboa Dump area. The fort’s principal islands, which were to later become known as the Fortified Islands, were the islands of Naos, Culebra, Perico, and Flamenco. Fort Grant also included the nearby unconnected islands of San Jose, Panamarca, Changarmi, Tortolita, Torola, Taboga, Cocovieceta, Cocovi, and Venado. These forts were gradually turned over to the Republic of Panama from 1979 to 1999, and the area is now a major tourist attraction and leisure area.

Although officially designated as Fort Amador by a War Department order in 1911, the entire area was commonly referred to as Fort Grant for a number of years. In designating Panama Canal fortifications sites and military reservations, the terms of reference used in early orders were relatively loose. On the Pacific side, the area that now comprises Fort Amador as well as the islands of Naos, Culebra, Perico, and Flamenco was referred to as Fort Grant by the Army. Consideration had been given to naming one of the artillery batteries in honor of Dr. Manuel Amador Guerrero, the first President of the Republic of Panama. Panamanians felt, however, that this was too insignificant an honor and it was subsequently decided to name the mainland portion of Fort Grant in honor of President Amador. It was not until 1917, when the widow of President Amador protested the Army’s failure to use the proper designation that the Commanding General, Panama Canal Department, issued an order (No. 16 – 19 October 1917) directing that the proper name be used hence forward.

In August 1911, when the Army broke ground in preparation for the construction of the Pacific fortifications, the area now known as Fort Amador was little more than a broad stretch of mud flats and swamp. Used as a dump for material removed from the canal, the area was appropriately referred to as “Balboa Dumps.” The Isthmian Canal Commission, however, had started building a breakwater from the dump area to Naos Island to protect the canal channel from cross currents. This breakwater was later extended to connect Naos with the other three islands. The flats on both sides of a portion of the breakwater were filled in to create Fort Amador. The breakwater that now constitutes the causeway extending from Fort Amador to the islands was solidly ballasted to support a railroad bed. During the construction phase, the railroad was used to carry material and machinery to the islands; later it was employed in hauling ammunition for the big guns, and when two railway guns were placed in service, the rail line was used to bring the guns to their firing positions on Culebra Island.

The Army started constructing quarters, administration buildings, and other permanent structures in 1915 and completed them by 1917. Fort Amador initially had three field grade officers’ quarters, one stable and wagon shed, eight company-size barracks, four four-family quarters, six two-family quarters, five noncommissioned officers’ quarters, one commanding officer’s quarters, one headquarters building, water and sewer system, and paved roads. The reservation contained many long ridges and deep ravines due to soil dumped by railcars, so the Army had to invest in additional fill and extensive grading.

Although Fort Amador was built and used primarily for housing the Coast Artillery Corps units that manned the big guns of Fort Grant, some armament was installed. The Army began building Batteries Birney and Smith in 1913 on the southern extremity of the post, on a little rise just north of the causeway; each battery had two six-inch disappearing guns (M1908 guns with M1905MII carriages). They remained in service until 1943, when the guns were removed and the structures buried. The Army replaced them with a 90mm anti-motor torpedo boat (AMTB) battery; the Army disarmed and buried the AMTB battery in 1948.

The first Army unit to be assigned to Fort Amador was the 81st Company, Coast Artillery, on 31 December 1913, followed by other coast artillery companies as the harbor defenses were completed. These companies were later organized into the 4th Coast Artillery (Harbor Defense) Regiment. In 1926, the 65th Coast Artillery Regiment was added to man the canal’s new antiaircraft defenses. During World War II, the Army deployed additional units and formed the Pacific Coast Artillery Brigade. Fort Amador also served as the headquarters of the U.S. Army Coast Artillery District (1919-47). Its coast artillery role ended in 1947 when the batteries of Fort Grant had been retired and armament removed.

Fort Amador then served as the headquarters of the senior Army commander in Panama from 1947 through September 1979—from the Army Caribbean Command (1947-63) through U.S. Army, Southern Command (1963-74) to the 193d Infantry Brigade (Canal Zone). After the Army headquarters moved to Fort Clayton in September 1979, part of the Army’s sector of Fort Amador and the islands were transferred to Panama on 1 October 1979. Most of post became headquarters of the Panamanian Defense Force until 1989. During Operation JUST CAUSE, Fort Amador was secured by 1st Battalion, 508th Infantry (Airborne), through an air assault with several buildings receiving damage from direct fire from 105mm howitzers and M60 machine guns. Portions of the post remained under American control until it was completely transferred to Panama on 1 October 1996.

Fort Grant was named in honor of General Ulysses S. Grant, commanding general of the Union armies in the Civil War and the eighteenth President of the United States. Grant actually spent several weeks on Flamenco Island in 1852 as part of the 4th Infantry’s journey to California that crossed the Isthmus of Panama. The four islands which comprised the “Fortified Islands” extend along the east side of the canal channel and were an ideal location for defensive fortifications. Being 12,000 to 14,000 yards south of Miraflores Locks, the islands were strategically placed to engage a hostile naval force before it could come within range of the Panama Canal’s vital installations. The causeway’s rail line linking these four islands with the mainland was used for constructing, supplying, and manning the coast artillery batteries and the controlled mine facilities.

Battery Warren on Flamenco Island mounted two Model 1910 (M1910) 14-inch rifles on disappearing carriages (DC M1907MI). With a traverse of 170 degrees and a range of approximately 24,000 yards, the two 14-inch guns commanded the entire area of seaward approach except for a small dead space behind Taboga Island. Located on the summit of Flamenco Island, the most seaward of the group, the battery was named in honor of Major General Gouverneur K. Warren.

Work began on Battery Warren in early 1912 and was completed, with guns installed, by 1917. Battery Warren included space for ammunition storage, fire control and plotting rooms, and power and communications systems. During construction, a special heavy-lift elevator was installed in a vertical shaft which was sunk 200 feet from the summit to connect with a horizontal tunnel which was entered from the mortar batteries on the north side of the island.

Practice firings were conducted regularly, with No. 1 Gun firing a total of fifty-seven practice rounds and No. 2 Gun 187 rounds. They were last fired on 8 December 1944, after which both guns were placed on secondary manning status. The four 155mm GPF guns on Panama mounts located in front of the battery were withdrawn at the end of World War II. The 14-inch guns were dismounted and scrapped in 1948.

The battery site continued to be used by Battery D, 764th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, using mobile 120mm guns from 1950 to 1960. Battery Warren was converted for use as a site for the HAWK missile system in 1960 when Battery F, 67th Artillery, later redesignated Battery C, 4th Missile Battalion (HAWK), 517th Artillery, arrived at Fort Grant. Much of the battery’s underground area was used in connection with the operation of the missile battery, while the concrete gun emplacements were filled in to provide sites for the mobile missile launchers and radar sets.

In addition to the 14-inch rifles atop Flamenco Island, the Army constructed a series of three mortar batteries in six dual pits on the landward side of the island just above the shoreline and designated them Batteries Merritt, Prince, and Carr. Battery Merritt was named for Major General Wesley Merritt, Battery Prince for Brigadier General Henry Prince, and Battery Carr for Major General Joseph Bradford Carr.

The three mortar batteries were similar, each having four 12-inch mortars. The mortars were M1912 that were installed on M1896MIII carriages located in high-walled concrete emplacements, which contained magazines, plotting rooms, and a large power plant. The mortars had a range of 17,900 yards and a 360-degree traverse, permitting them to cover all approaches to the canal. At extreme range, rounds could be dropped about one mile beyond Taboga Island. The Army began construction of the batteries in 1912 and all weapons were in place by 1916. All were scrapped in 1943.

The area formerly used to accommodate these three mortar batteries was the site of barracks, a mess hall, and administrative buildings for Army antiaircraft artillery, and later the HAWK missile unit until 1970. The Army used Flamenco Island as a storage area until 1979 when the island was transferred to Panama. Under General Manual Noriega, the island was used as a political prison until 1989. It was subsequently handed over to the Panamanian national maritime service; this later moved to the former Rodman U.S. Naval Station in 1999. Around 2002, a two-level shopping mall was built over two of the mortar batteries (except for Battery Merritt) and part of Battery Warren was destroyed for a hotel that was never built. The battery’s unique access tunnel and elevator shaft still exist but are abandoned.

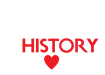

Battery Newton, named in honor of Major General John Newton, was erected on top of Perico Island at an elevation of some 230 feet. The battery had one 16-inch rifle (M1895) mounted on a disappearing carriage (M1912). This was the largest Army weapon of its type at the time and was one of two such weapons on disappearing carriages, the other being an M1919 gun on an M1917 carriage as part of the Long Island Sound defenses on Great Gull Island (Fort Michie). This 35-caliber gun had a range of 22,600 yards and a traverse of 170 degrees. The gun weighed 284,000 pounds and took seven years to complete (1895-1902). It was not until ten years later it was shipped to Panama. Its limited of elevation of only twenty degrees on the disappearing carriage resulted in its 2,400-pound shell traveling a relative short distance.

Construction of the emplacement for Battery Newton began in 1914 and all work, including the mounting of the 16-inch rifle, was completed by 1917. To aid construction and ammunition deliveries, the Army constructed a rail line to the top of Perico that wrapped around the island. The Army also built a special concrete staircase to allow the gun crew to scramble from their seashore barracks up to the gun emplacement. In early 1943, the gun was placed on standby manning basis and was dismounted and scrapped later that same year.

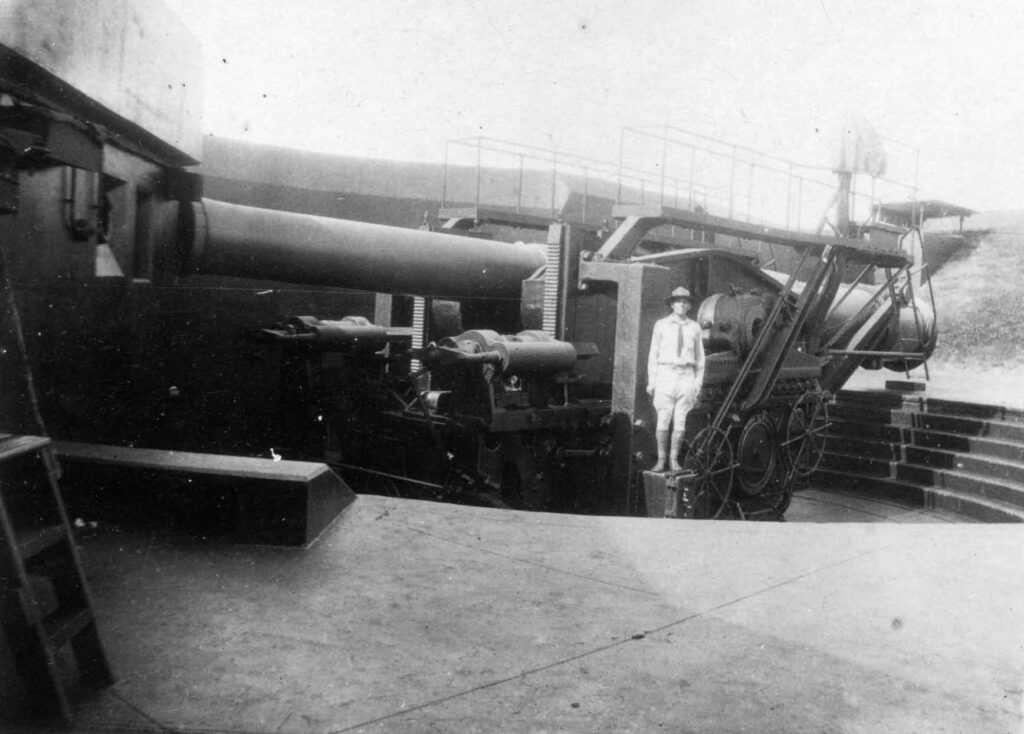

The site of Battery Newton was converted for use as a radar installation originally operated by the Federal Aviation Agency (now by Panama’s Autoridad Aeronáutica Civil) for civil aviation in the region. The underground facilities are abandoned but the old railroad bed, including a tunnel near the top of the hill, still remains.

Along the top of the 100-foot ridge that forms Naos Island were Batteries Buell and Burnside. Battery Buell was named in honor of Major General Don Carlos Buell and Battery Burnside for Major General Ambrose E. Burnside. Each of the two batteries mounted two 14-inch rifles (M1910) on disappearing carriages (DC M1907MI). With a range of some 24,000 yards and a 170-degree traverse, the large caliber guns covered virtually every possible approach to the Pacific entrance of the canal.

Each battery was an independent installation with its own ammunition magazines, plotting rooms, and communications systems, with an underground passage that connected all four guns. Construction of the two batteries began in 1912 and was completed by December 1916. During regular practices, No. 1 Gun, Battery Buell, fired 119 rounds and No. 2 Gun fired 102 rounds. No. 1 Gun, Battery Burnside, fired a total of ninety-four practice rounds and No. 2 Gun shot 105 rounds.

By World War II, the four 14-inch rifles were considered obsolete, and although they were fired as late as 15 November 1943, they were not manned in 1944-45. The guns were dismounted and scrapped in late 1947 or early 1948. The emplacements for Batteries Buell and Burnside were used for storage of civil defense supplies and for the U.S. Army Forces, Southern Command, Museum until 1 October 1979, when Naos Island was transferred to Panama.

Naos Island was also the site of Battery Parke, named in honor of Major General John G. Parke. The battery was equipped with two 6-inch rifles (M1908 on M1905MII disappearing carriages), each with a range of 6,000 yards. The battery was constructed from 1913 to 1915 and its armament was removed and dumped at sea in August 1946. Located just east of Battery Burnside but at the island’s waterline, it was destroyed in 2004 to make room for a large residential condominium structure.

Located on the north side of Naos Island was a mine storehouse, cable tank house, explosive magazine, loading room, mine casemate, power plant, and mine boathouse and wharf to support the control mine defenses of the approaches to the Panama Canal. While the composition of this underwater defense varied from 1916 to 1950, by the end of World War II there was an outer defense of sixteen groups of thirteen M4 ground mines and an inner defense of ten groups of thirteen M4s. A fleet of Army mine planters, distribution box boats, and yawls were stationed at Naos Island. Three ordnance workshops were located on the island and used for storage and repair of the guns of Fort Grant. Behind these buildings were long staircases that ran up to Batteries Burnside and Buell for gun crew access.

The top of Naos Island and the 14-inch batteries were filled in to prepare for the construction of a hotel that was never built. The fire control stations for these batteries have been destroyed for the construction of a large water tank. The control mine complex is currently occupied by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s Marine Laboratories.

In 1928, the first of two 14-inch railway guns (M1920MII on M1920 railway carriages) was brought to the Panama Canal Zone. The maximum range of these guns was 48,000 yards, double the range of the 14-inch rifles of Batteries Buell and Burnside. The first gun was placed on a temporary spur at Fort Amador to await the rebuilding of the causeway railroad track and the completion of two firing positions on Culebra Island. The following year the second gun arrived. The Army constructed firing turntables on piles at both Fort Randolph on the Atlantic side of the canal and at Fort Grant on Pacific side, so these two railway guns could travel across the isthmus depending on the greatest enemy threat. Long garage-like magazines with overhead trolleys which were cut into the island adjoining the track were built near the two firing positions on Culebra Island. The island also supported two 155mm guns on Panama mounts, as well as several 75mm guns on mobile mounts.

The United States transferred Culebra Island to Panama on 1 October 1979 and it was largely abandoned except for a beach house built by General Noriega. In 1992, the island became the Punta Culebra Nature Center as a facility for science education and to foster connections between Panamanians and their natural heritage. The center is run by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and turned the 14-inch railway gun ammunition storage into exhibit and conference space.