Written By: Emily George

“The beginnings of great periods have often been marked and made memorable by striking events. Out of the cloud that hangs around the vague inceptions of revolutions, a startling incident will sometimes flash like lightning, to show that the warring elements have begun their work.” Published in July 1861, this excerpt from an article by John Hay, President Abraham Lincoln’s secretary, described the rapid dissolution of the Union and the impending Civil War. Though the tensions between the North and South had been building for years, in early 1861, an actual impetus to cause a definitive break in the nation remained elusive. One “startling incident,” however, would precipitate the looming war. Interestingly, Hay’s words were not a reference to the events at Fort Sumter in April 1861. Rather, Hay wrote of another dramatic event that occurred weeks later, on 24 May, just one day after Virginia seceded from the Union. On that day, the Union Army suffered the death of its first officer—Colonel Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, commander of the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

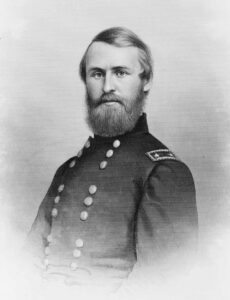

Ellsworth’s death resonated so greatly throughout the North that it is somewhat shocking at how little-known his name is today. A close friend of President Lincoln and Hay, Ellsworth was a prominent figure in the White House. His death shook Washington, DC, and affected people throughout the North. His body lay in state at the White House before being returned to his home state of New York. Thousands of mourners lined up to view his casket in New York City before his burial at Hudson View Cemetery in Mechanicville, New York. At only twenty-four years of age, Ellsworth had hardly reached adulthood at his death, yet he had already made a significant impact on the nation. Hay would assert, “No one ever possessed greater power of enforcing the respect and fastening the affections of men. Strangers soon recognized and acknowledged this power; while to his friends he always seemed like a Paladin or Cavalier of the dead days of romance and beauty.”

Upon receiving the news of Ellsworth’s untimely death, Lincoln, filled with grief, sent a letter to the young man’s parents. He expressed his condolences, writing:

So much of promised usefulness to one’s country, and of bright hopes for one’s self and friends, have rarely been so suddenly dashed, as in his fall. In size, in years, and youthful appearance, a boy only, his power to command men, was surpassingly great. This power, combined with a fine intellect, an indomitable energy, and a taste altogether military, constituted in him, as seemed to me, the best natural talent, in that department, I ever knew.

Ellsworth was born on 11 April 1837 to Ephraim and Phoebe (Denton) Ellsworth in Malta, New York. Ephraim’s father had fought in the Revolutionary War, and Elmer was seemingly destined to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps. From a young age, he had a keen interest in military tactics and history. He dreamed of attending West Point, but a lack of money and proper education deemed that unfeasible. While growing up near Mechanicville, he put his fascination with the military into action by organizing his peers into the “Black Plumed Riflemen of Stillwater.”

In 1853, Ellsworth moved to New York City at the age of sixteen. Continuing to pour over books on military tactics and procedures as often as possible, he attended military drill unit displays and exhibitions whenever they were held in the city. In 1854, he moved to Rockford, Illinois, to become a patent agent. Through his military studies, he also developed a fascination with uniforms. Reading newspaper articles on the Crimean War, he was exposed for the first time to the Zouaves, French colonial troops in Algeria who wore colorful uniforms.

Ellsworth moved to Chicago in 1856, where he met Charles A DeVilliers, a surgeon who served in the French Zouave regiment during the Crimean War in 1854. Now in Chicago, he happened upon young Ellsworth and mesmerized the boy with the training and tactics of the Zouaves. DeVilliers taught Ellsworth the art of fencing, making him one of Chicago’s most talented swordsmen. As many books on the Zouave system were in French, Ellsworth studied the language to fully immerse himself in Zouave tactics and discipline.

Building off his growing knowledge of Zouave tactics, Ellsworth created his own regimen for living an honorable and disciplined life. Though he took it upon himself to organize and drill a number of militia units, he developed a custom of refusing to be paid for his services. He carried this philosophy further, refusing any favor he was not able to repay. He often declined dinner invitations, content to starve rather than be in debt to someone.

As was popular at the time, Ellsworth had organized a small militia unit to perform elaborate drills at exhibitions for the public. Gaining notoriety for their strict discipline and ornate uniforms, Ellsworth’s Zouaves were soon known beyond the city of Chicago. Ellsworth required his men to follow the same practice of self-discipline that he did. While on tour around the area, his men were encouraged to welcome the hardships of life and were rarely allowed to sleep in beds.

With their reputation growing across the nation, Ellsworth and his men went on a tour of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states. Fifty men set out on the twenty-city tour after losing some who could not stand the physical rigors of the drilling and others who were prone to drinking. Performing against other militia units in the various cities, Ellsworth’s Zouaves were consistently the crowd favorite.

During his time in Chicago, Ellsworth proposed to Carrie Spafford, whose father was a prominent banker in Illinois. Miss Spafford’s parents would not approve the union until Ellsworth proved he could support himself and his wife. Her father encouraged him to study law, a subject that for Ellsworth seemed far from the excitement of military life.

Interestingly, or perhaps fortuitously, around the same time, Abraham Lincoln, then a lawyer in Springfield, had become intrigued by news of the young Ellsworth and his disciplined Zouaves. A friendship soon developed between the two men beginning in 1859. Again, Ellsworth gained a friend who would dramatically change his life. Ellsworth became a clerk in Lincoln’s office, while Lincoln encouraged Ellsworth’s continued training of militia in the area.

Though not enamored with the study of law, Ellsworth impressed Lincoln in other ways. His dedication to military discipline, tactics and training, were undoubtedly remarkable. Yet, based on descriptions of the young man, Ellsworth’s appearance and demeanor appear to have captivated many individuals. Hay described him in detail:

His person was strikingly prepossessing. His form, though slight—exactly Napoleonic size—was very compact and commanding; the head statuesquely poised, and crowned with a luxuriance of curling black hair; a hazel eye, bright, though serene, the eye of a gentleman as well as a soldier; a nose such as you see on Roman medals; a light moustache just shading the lips, that were continually curving into the sunniest smiles. His voice, deep and musical, instantly attracted attention; and his address, though not without soldierly brusqueness, was sincere and courteous.

Ellsworth participated in Lincoln’s 1860 campaign for the presidency. Lincoln hoped the popularity of the young drillmaster would add vitality to his campaign. Following Lincoln’s victory, Ellsworth was part of the detail assigned to escort the President-elect to Washington for his inauguration in March 1861.

As Ellsworth had spent many hours creating his own version of militia reforms for the country, he hoped that the election of Lincoln would give him the opportunity to put his ideas into practice. He believed in the necessity of establishing a Bureau of Militia within the War Department. Through this office, he envisioned a more consolidated and uniform system of militias in the many states. Because of his strong belief in the importance of uniformity and strict drilling, Ellsworth hoped to turn the state militias into powerful and disciplined military units.

Lincoln also felt Ellsworth would be an appropriate addition to the War Department. In a letter to his current Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, on 18 March 1861, Lincoln wrote:

Sir: You will favor me by issuing an order detailing Lieut. Elmer E. Ellsworth, of the First Dragoons, for special duty as Adjutant and Inspector General of Militia for the United States, and in so far as existing laws will admit, charge him with the transaction, under your discretion, of all business pertaining to the Militia, to be conducted as a separate bureau…

Yet, with the secession of several Southern states, further discussion of revamping the War Department became less of a priority. With war becoming increasingly imminent, Ellsworth understood the necessity of setting militia reforms aside at present. He eagerly anticipated a fight to restore the Union. In speaking to Hay, he explained, “You know I have a great work to do…I am the only earthly stay of my parents; there is a young woman whose happiness I regard as dearer than my own: yet I could ask no better death than to fall next week before Sumter. I am not better than other men. You will find that patriotism is not dead, even if it sleeps.”

In response to the attack on Fort Sumter on 12 April 1861, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers for three months of service. Ellsworth took it upon himself to go back to his home state of New York and organize a regiment that met his own high standards. Ellsworth’s new regiment, the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry would become known as the “Fire Zouaves,” as it was made up largely of firemen from Manhattan who had little or no military training. However, in remarkably short time, Ellsworth arrived back in Washington with his 1,100 able men in May 1861.

Four states—Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina–seceded from the Union in response to Lincoln’s call for volunteers, joining the seven states that had already left. Virginia’s secession, however, first voted on by a special session of its General Assembly on 17 April 1861, was not official until ratified by its citizens on 23 May 1861. Now, the Fire Zouaves eagerly awaited the order to cross the Potomac into the rebellious state.

The Marshall House, a hotel in Alexandria, Virginia, flew a Confederate flag over the building. In full view of the White House, the flag seemed to taunt all those in the capital city. On the night of 23 May, Lincoln and Lieutenant General Winfield Scott ordered Ellsworth and his men to be prepared to advance into Virginia and occupy the city of Alexandria. During the preparation to cross the Potomac, as though anticipating his approaching demise, Ellsworth wrote two letters, one to his fiancée, Carrie, and one to his parents. Both expressed the potential danger of his mission and his love for them.

Ellsworth and his men moved into Alexandria early on 24 May and met no resistance. Once the town was relatively secured, Ellsworth and a handful of men went to the roof of the Marshall House, in search of the large Confederate flag still flying. As Ellsworth descended the stairs, captured flag in hand, he was shot through the heart by James Jackson, the owner of the hotel. One of Ellsworth’s men, Corporal Francis E. Brownell, immediately returned fire, killing Jackson. As Ellsworth lay dying, one of his men found a gold medal on his chest with the inscription, Non Sol Nobis, Sed Pro Patrio (Not for Ourselves, but for Our Country).

News of Ellsworth’s death traveled quickly throughout the North. Lincoln struggled with the grief of losing his young friend in addition to the pressure of addressing the growing conflict among the states. Indignant over the killing of a man who was not only a Union officer, but also a close friend of the President, Northerners grew increasingly eager for war. Prominent individuals in New York called for the creation of a new regiment from the men of the entire state to avenge the young officer’s death. The soldiers were to come from every town and ward in the state, and be unmarried, no shorter than 5’8’’ and no older than thirty. The result was the 44th New York Infantry Regiment, which would gain the nickname of “Ellsworth’s Avengers.” The regiment was organized in August 1861 and joined the Army of the Potomac in late October 1861 in Virginia. The regiment would gain glory for its gallantry at Gettysburg. It would also participate in the Battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. It was mustered out of service on 11 October 1864. Throughout its service to the Union Army, its battle cry remained: “Remember Ellsworth!”