By Matthew J. Seelinger

In the early years of the Revolutionary War, American militia forces and Continental troops demonstrated they had the will to take on the British Army, inflicting heavy losses at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, while winning victories at Trenton and Princeton. Wars, however, are won by more than willpower and courage—victory also requires weapons, especially when battling one of the most powerful military forces in the world. To that end, the French, longtime rivals of Great Britain in Europe and North America, became an invaluable ally to the American cause, supplying thousands of muskets to the Continental Army, specifically the Charleville Musket, France’s standard infantry firearm since its introduction in 1717.

When the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord on 19 April 1775, the Massachusetts militiamen who engaged the redcoats were armed with an assortment of firearms, including hunting weapons such as flintlock fowlers, so-named because they were used for hunting fowl of various types. Others carried muskets similar to the British “Brown Bess,” the standard British infantry weapon, officially designated the Land Pattern musket, and manufactured by American gunsmiths under contract by colonial Committees of Safety. These weapons all had key features in common, including the fact that they were smoothbore (the barrels did not have rifling), and they were all flintlocks that used flints to ignite the powder that fired a musket ball, buckshot, or “buck and ball,” a combination of the two.

While the Americans demonstrated that they could stand up to British regulars and the mercenary Hessian troops fighting alongside them, the Continental Army was plagued by shortages, including gunpowder, ammunition, cannons, and, most importantly, muskets, as American gunsmiths simply could not meet the demand for firearms. To remedy this, American agents began reaching out to France, Great Britain’s longtime rival, to purchase weapons. France soon responded by supplying thousands of what was considered one of the finest muskets in the world at the time—the Charleville.

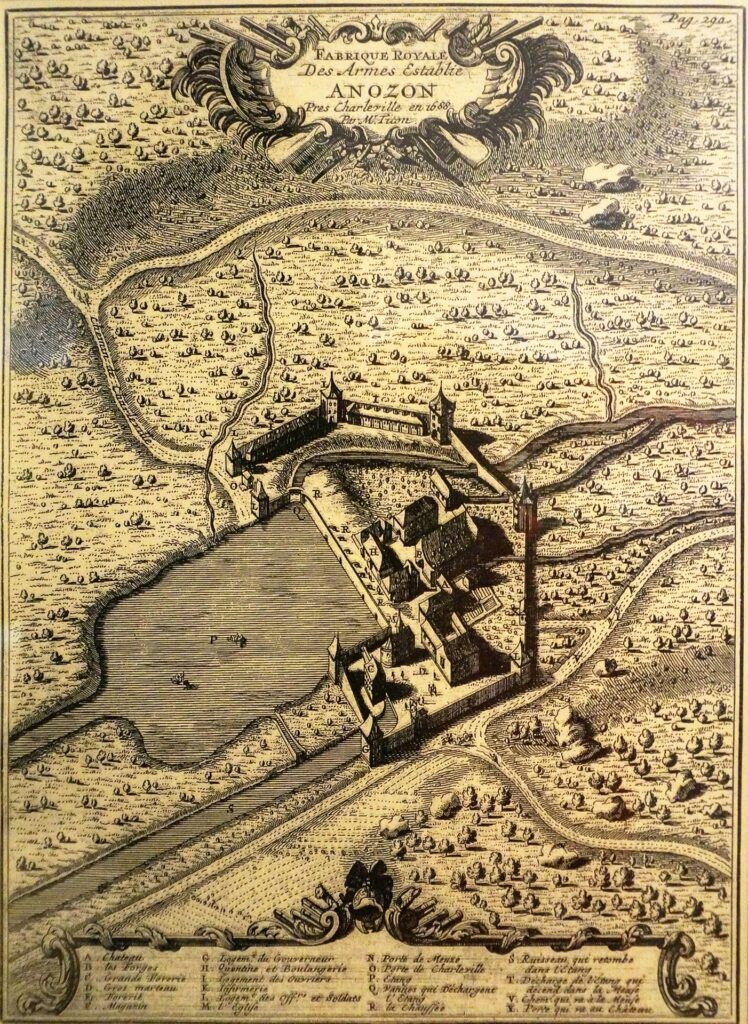

Developed in the early eighteenth century and introduced in 1717 as the French Army’s first standardized musket, the Charleville was more correctly called the French Infantry Musket or French Pattern Musket, but it became more commonly known as the Charleville for the place where many of the weapons were manufactured, the armory at Charleville-Mézières, Ardennes, France. The muskets were also produced at other armories, including Tulle, Saint-Étienne, and Mauberge.

The original Model 1717 had a forty-six-inch-long barrel and an overall length of sixty-two inches. The barrel was attached to the stock by a series of pins that would be replaced by three metal bands that became standard on subsequent models. The Charleville could be equipped with a socket bayonet with an overall length of eighteen to twenty inches and a blade length of fifteen to seventeen inches. It weighed approximately nine pounds, and its wooden stock was made from walnut.

The Charleville fired a .69 caliber round ball made of soft lead, slightly smaller and lighter than the .75 caliber round fired by the British Brown Bess, but still a capable military round that could inflict catastrophic wounds. A well-trained soldier could fire three, and as many as four, shots per minute, but this rate declined as a battle wore on, and repeated firing fouled the barrel with black powder residue that made reloading more difficult. Furthermore, misfires were relatively frequent, and flints needed to be replaced after approximately thirty rounds.

Like most muzzle-loading smoothbores of the era, the Charleville was not a very accurate weapon. While a soldier armed with a Charleville could reliably hit a formation of enemy troops at 200 yards, eighty yards was about the maximum range to hit an individual soldier. Infantrymen did not usually aim at their targets; rather, lines of soldiers pointed their muskets at an enemy formation and fired as they closed with the opposing side. If one side began to waver, then the other would charge with bayonets, often bringing a conclusion to the battle with the use of “cold steel.”

Over the next several decades, the Charleville underwent several minor modifications, mostly in the musket’s weight and length. By the time of the American Revolution, French armories had manufactured over 600,000 Charlevilles. It was considered a superior weapon to the British Brown Bess as it was lighter and had slightly better accuracy.

Realizing the Army would need more weapons and other necessary tools to wage war against the British, the Continental Congress began efforts to purchase firearms and other materiel from France in 1776. Beginning in early 1777, the first shipment of arms arrived from France at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The Marquis de Lafayette reportedly brought several hundred with him as a gift when he arrived in America that same year. More began arriving in 1778 once France officially entered the conflict on the American side. In all, France supplied as many as 48,000 (some reports say as high as 100,000) Charleville muskets to the Continental Army.

The Continental Army was equipped with two models of the Charleville, the 1763 and 1766. The Model 1763 was the first redesign of the Charleville following the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War in North America). The barrel was shortened by two inches, from forty-six to forty-four inches, the butt straightened, and the ramrod given a more trumpet-shaped end. While Model 1763 was shorter in length than earlier ones, it was designed to be heavier and sturdier, and its weight increased to just over ten pounds. Three years later, the Charleville underwent another redesign. Since the Model 1763’s design was determined to be slightly too heavy, French gunsmiths made several changes, including thinning the barrel, shortening the lock, slimming the stock, replacing the long iron ramrod cover with a pinned spring under the breech, and swapping out the trumpet-shaped ramrod for one with a lighter button-shaped end. Despite being thinned down and lighter, the new Model 1766 proved to be a rugged and reliable weapon. The Model 1766 would heavily influence the design of the Springfield Model 1795 Musket, the first regulation musket manufactured in the United States and adopted by the U.S. Army.

It is often incorrectly believed that Continental troops also received Model 1777 Charlevilles. This model was only used by French troops serving on American soil under General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, against the British. Small numbers of French troops were also equipped with the earlier Model 1766.

Several nations either adopted Charlevilles for their armies or based their own firearms on the Charleville design, including Belgium, Austria, Prussia, Russia, and the Netherlands. French forces used the Charleville in the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, and French armories continued to produce the muskets until 1840, when they fell out favor due to the reliability of percussion locks over flintlocks. However, some Charlevilles were converted to percussion locks, and a number Dutch examples were converted to breechloaders in the 1860s. In all, the French manufactured between seven and eight million Charlevilles, many of which can be found in museums around the world, as well as on the antique firearms market. Reproductions of the Charleville can also be found in museums and carried by reenactors and living historians of the American War of Independence and other conflicts.

About the Author:

Matthew Seelinger is the Army Historical Foundation’s Chief Historian and Editor of On Point, and has worked for AHF since 1997. He holds a B.A. in History from James Madison University and an M.A. in History from Ball State University. A native Virginian, he lives in Arlington with his wife Elisabeth, an archivist for the U.S. Senate, and three cats.