Written By: Howard E. Bartholf

Camp Merritt was located on land that today makes up parts of several Bergen County, New Jersey, towns, including Bergenfield, Cresskill, Dumont, Tenafly, and Demarest. The camp, which once encompassed over 770 acres, was the largest embarkation camp in the United States during World War I.

The camp was named for the famous Civil War cavalry officer Wesley Merritt (1836-1910). Following the Civil War, Merritt served in the Indian Wars and was the Superintendent at West Point from 1882 through 1887.

In 1895, Merritt was promoted to the rank of major general. During the Spanish-American War, he commanded VIII Corps and led American ground forces in the capture of Manila.

He was later the first Military Governor of the Philippines. He would also serve as the commander of the Department of the East until his retirement in June 1900.

Camp Merritt, New Jersey, should not be confused with another Camp Merritt, which opened in May 1898 in the Richmond District of San Francisco, California.

This camp, originally called Camp Richmond, was created to process troops of the Philippine Island Expeditionary Forces. It later closed on 27 August 1898.

Construction of the camp at Cresskill began in September 1917. MacArthur Brothers Company, Engineers and Contractors, of New York was selected as the primary contractor. The site for the camp had been selected during the Spanish-American War but was never developed. Hundreds of local carpenters, electricians, and other tradesmen were employed in the construction of the camp.

The first troops to arrive were from Company F, 22d Infantry, on 30 August 1917, followed by the 49th Infantry on 17 September. At that time, there were no buildings to house the men, so they were quartered about a mile north of the camp on what was an old horse racing track, now the site of Northern Valley Regional High School at Demarest. Between November 1917 and November 1918, 578,566 men would pass through Camp Merritt on their way to Europe. Of these, 16,052 were officers and 562,514 were enlisted personnel.

Among those officers who spent time at Camp Merritt would be a future President of the United States, Harry S. Truman. Captain Truman served with the 129th Field Artillery, a unit attached to the 35th Division.

He arrived at Camp Merritt from Camp Doniphan, Oklahoma, on 23 March 1918 and left the camp on 28 March 1918.

His unit made the crossing on the SS George Washington, arriving in France on 14 April. While at Camp Merritt, Truman was able to visit New York City and wrote at least two letters to his beloved wife Bess from the camp.

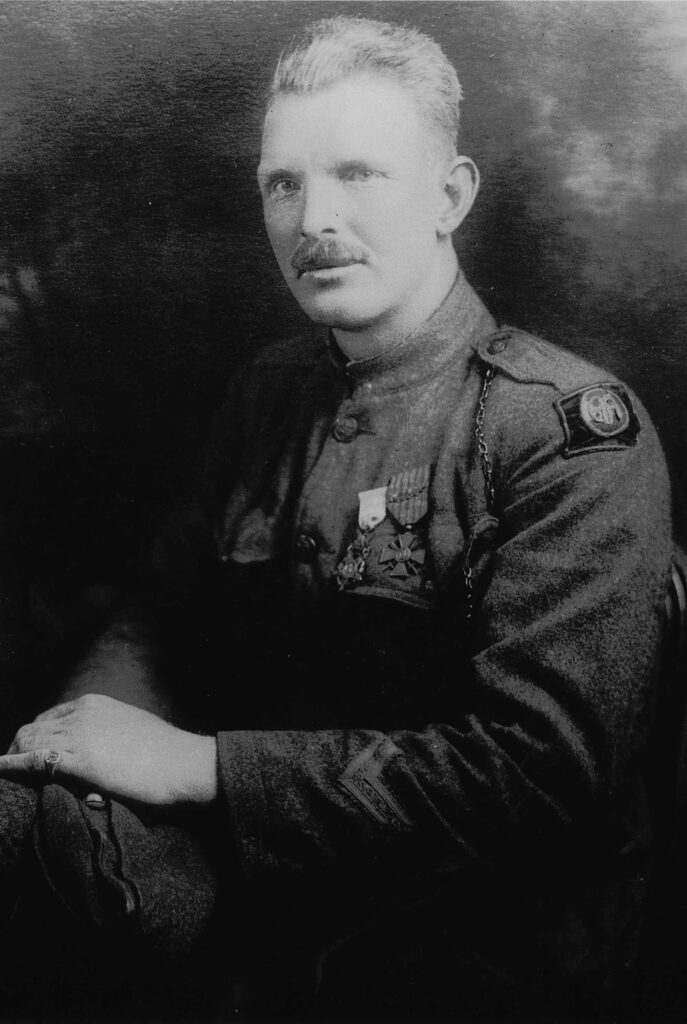

After the end of hostilities, Sergeant Alvin C. York, the famed marksman and Medal of Honor winner, would pass thru Camp Merritt on his way home to Tennessee.

Arthur Godfrey, the famous aviator and radio (and later television) broadcaster, would serve as a civilian typist at the camp as a young boy of fifteen.

Hank Gowdy, a catcher for the Boston Braves who led his team to the 1914 World Series title over the Philadelphia Athletics, was the first Major League baseball player to enlist. Color Sergeant Gowdy served with the 166th Infantry, 42d (Rainbow) Division, and would return to the United States through Camp Merritt in April 1919.

Thomas C. Neibaur, the first Mormon to earn the Medal of Honor, went to France via Camp Merritt with the 41st Division. He was later assigned to the 167th Infantry of the Rainbow Division.

Another soldier by the name of George L. Fox would pass through Camp Merritt on his way to France. He served in the Ambulance Corps and was awarded a Purple Heart and Silver Star for his actions. Following the war, he would become a Methodist minister and re-enter the Army during World War II as a chaplain. In February 1943, he was one of four chaplains who gave up their life jackets to save fellow soldiers during the sinking of the troopship USAT Dorchester. He would be awarded a second Purple Heart and the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously.

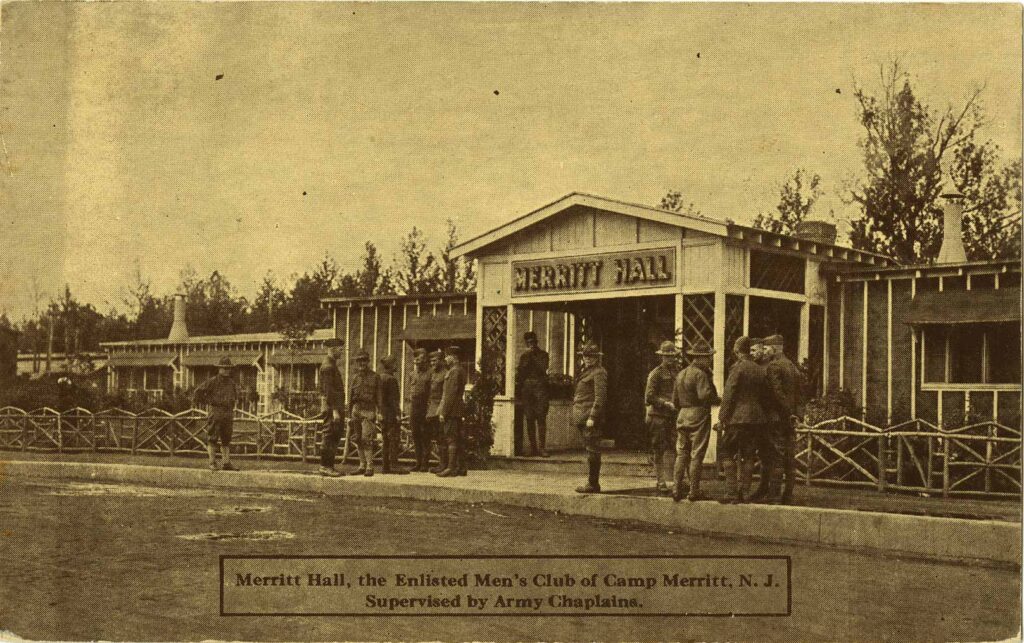

Merritt Hall, the large soldier’s club on post, opened on 30 January 1918, and was dedicated by former President Theodore Roosevelt. Merritt Hall was called “The finest soldiers club in America” by Major General David C. Shanks, who served as commanding officer of the Port of Embarkation at Hoboken.

There were four Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) buildings at the camp and several American Red Cross buildings. New Jersey Governor Walter Evans Edge, who served as New Jersey’s governor in both World Wars, would later address soldiers at one of the YMCA buildings.

Henry P. Davison, Chairman of the American Red Cross, dedicated the officers club in 1918. In the spring of that year, the camp theater, the Liberty Theater, opened with the noted playwright Augustus Thomas giving an opening address.

The soldiers of Camp Merritt had the opportunity to hear from the Poet Laureate of England, John Masefield, when he visited the camp in 1918. In his address to the assembled troops, he declared, “Your race, alone among the races of the world, has never gone to war, except for liberty. Firstly for independence, then for freedom from aggression, then for the freeing of slaves, then for the freeing of Cuba.

Be sure that all those who died in those causes exist eternally to help on all lovely causes wherever there are men.” Masefield’s address helped to steel the soldiers’ minds and bodies for the conflict they would soon find themselves in.

There was apprehension among the troops at Camp Merritt, especially when news arrived that two British troopships, the Tuscania and Otranto, had been lost off the coast of Scotland in February and October 1918. Both ships were carrying hundreds of American soldiers, many from Camp Merritt, and dozens of soldiers lost their lives.

The camp would not be immune to the effects of the dreaded influenza pandemic of 1918 that ravaged much of the world. The epidemic at Camp Merritt began on 19 September, with fifty-eight soldiers being admitted to the hospital. Within three weeks, there were 999 cases with 265 deaths, a mortality rate of 26.5 percent. The rate of new cases was so great that it greatly taxed the capabilities and resources of the base hospital. As a result, many soldiers had to be sent to Englewood Hospital in Englewood, and Saint Mary’s Hospital in Hoboken. For a time, Saint Mary’s would be known as Embarkation Hospital Number One. Many soldiers became sick during the time they left camp as they prepared to make the journey to Europe.

Several troop trains of sick soldiers were brought back from the Port of Embarkation at Hoboken to be admitted to the base hospital. In one day alone, over 600 soldier patients would be transferred from the ships. Many other soldiers who had previously been healthy contracted the disease while crossing the Atlantic and brought the illness with them to the battlefields of the Western Front. The camp’s main hospital had a monthly newspaper called The Mess Kit. The March 1919 edition made mention of the importance of the hospital and its staff of doctors, nurses, and orderlies. The commanding officer of the hospital at that time was Major Jessie I. Sloat.

He was quoted as telling a sergeant in the sick and wounded office that “The men in these offices have worked night and day, without rest, for weeks on end, to meet these conditions. I have never known such ungrudging service, so little complaint; such genuine loyal co-operation and determination to put the thing through; to get the work out; to keep the wheels from stopping; to keep things moving. If it had not been for this devoted service on the part of the enlisted men in this command, we should have faced an impossible task. They made it possible to bring it to a successful ending.” The paper made the statement that “Not all the heroism was on the battlefields of France.” In January 1919, as the Army demobilized, the soldiers at Camp Merritt took up a collection and coined a special medal with a red, white, and blue ribbon. These medals were presented to local school children in appreciation for their support of the troops. A total of 37,624 medals were presented to children at 147 schools.

On 21 March 1919, the War Department announced that twenty-seven camps would be abandoned, including Camp Merritt. On 8 April 1919, the Cunard liner Mauretania arrived in New York, with 2,700 American officers and men who had served in the British Army between 1915 and 1917. 2,100 men went to Camp Mills and 600 went to Camp Merritt for processing. Each man had to have his identity and citizenship verified before they were released. Secretary of War Newton Baker paid a visit to Camp Merritt on 30 May 1919. He addressed 25,000 troops on Memorial Day and inspected the camp. This was the first Memorial Day observance at the camp following the Armistice. Regarding the sacred dead from the war, Newton remarked, “These men are not just dead and buried, their spirit will live on forever, the same as the men who gave their lives in the War of the Revolution and in the Civil War.”

Camp Merritt officially closed in late January 1920, with the last troops arriving from overseas on 26 January. Following the decision to close the camp, the Army ordered that it be dismantled. The contract to take the base apart and salvage materials was awarded to the firm of Harris Brothers of Chicago for $552,554. Many of the buildings that made up the camp and had not been dismantled were destroyed by a series of three fires that took place in March and June 1921 and April 1927. During one of these fires, a building containing dynamite was emptied before the fires could reach it. After the abandonment of the property, it reverted back to the various landowners who had leased the land to the government.

Over the years the properties were sold off and developed into various single family housing projects.

There were few signs that the camp ever existed by the late 1940s and early 1950s. Occasionally, one would come across some block or slab of concrete that would indicate a building or military obstacle course had been there. A May 2004 newspaper article stated that a large stone was found on the property of Mrs. Patricia Brassel of Cresskill with the following inscription, “Company K, Casual Bn.”

Two railroads served the camp—the Erie Railroad in Cresskill and Tenafly, as well as the West Shore Railroad that ran through Bergenfield and Dumont. The old Cresskill railroad station, which served as the camp’s main railroad depot, stood until November 1970, when it was demolished following a fire. It was through these stations that thousands of American soldiers departed Camp Merritt for the trip to Hoboken, where they boarded ships for Europe. They would return in the same manner following the war for discharge or reassignment processing.

Soldiers would also march out of the camp early in the morning and march up the hills to Alpine, New Jersey, and down the cliffs of the Palisades to a landing on the Hudson River. This was a distance of about five miles. There they would board small ships to be taken down river to the awaiting troopships at Hoboken. This was basically the same route the British and Hessian army used in 1776 as they tried to capture George Washington’s army then stationed at Fort Lee, near the site of the George Washington Bridge. One building that still stands in Cresskill, and was there when Camp Merritt was thriving, is the Congregational Church. The present building was erected and dedicated on 7 March 1909 and undoubtedly gave spiritual comfort to many soldiers. Other local churches, such as Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church in Tenafly and Saint Cecilia’s in Englewood, provided support to the troops at the camp, forty percent of which were estimated to be Roman Catholic.

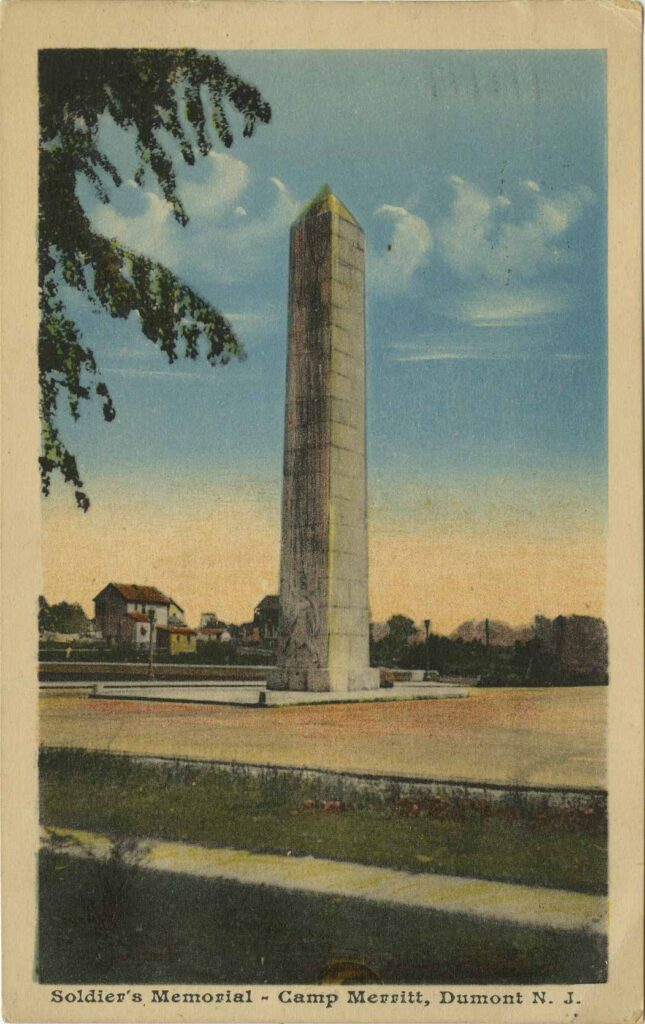

The Camp Merritt Monument was dedicated by General of the Armies John J. Pershing on 30 May 1924. In addition to the dedication address by General Pershing, the Governor of New Jersey, George S. Silzer, addressed the crowd of thousands. Mrs. Laura Williams Merritt, widow and second wife of Major General Merritt, was also present for the dedication. The sixty-five foot tall granite obelisk is inscribed with the names of fifteen officers and 558 enlisted men, as well as four nurses and a civilian, who died at Camp Merritt during the war. The monument was built by Harrison Granite Company of New York with granite from the Stoney Creek Quarry in Connecticut. The sculpture of the helmeted soldier, with sword in hand at the base of the monument, was commissioned by the famed artist Robert Aitken, a former Army officer. The monument is located in a traffic circle at what was the geographic center of the camp.

Some local streets in Cresskill still carry names that relate back to those military days. Merritt Avenue is named after the camp’s namesake and Pershing Place recognizes the AEF commander. Stivers Street is named after LTC David Gay Stivers, the soldier who supervised the construction of the post. Stivers was later wounded in the Meuse-Argonne Campaign and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry in action. Few people today, living on or passing through what was Camp Merritt, know how important a part the camp played or the contribution that it made to victory in World War I. At the time of this writing, only one soldier who passed through Camp Merritt is still living. Mr. Frank Buckles age 107, of Charles Town, West Virginia, passed though the camp during the winter of 1917. He is the last surviving American World War I veteran.