By Danny Johnson

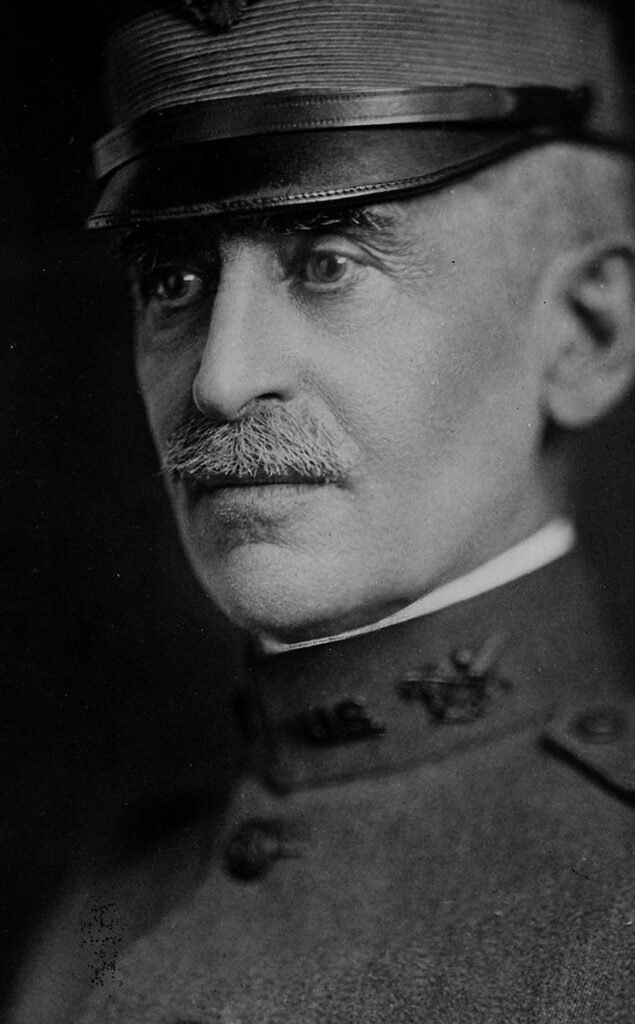

The initial political support for a new Signal Corps Replacement Training Center came from Republican Congressman Dewey Short of Missouri in 1941, who sponsored legislative action on Capitol Hill for a signal training center in the foothills of the Ozarks. The Army broke ground for what became Camp Crowder on 30 August 1941, approximately three miles southeast of Neosho, in Newton County, Missouri. The post was named for MG Enoch H. Crowder (1859-1832), a native Missourian who attained fame as the author of the Selective Service Act of World War I. As the Provost Marshal General, he was responsible for the administration of conscription during World War I in the United States. Most of the land used for Camp Crowder was then rolling farmland, dotted with small orchards, corn fields, and modest farm homes. The first soldiers arrived on 2 December 1941, just five days before the Pearl Harbor attack.

Camp Crowder was originally designated to be a triangular infantry division training center. A civilian engineer, however, in Neosho studied the Crowder maps and saw that a Shell Oil Company pipeline cut right through what was to become the artillery impact areas. As a result, the original plans for Camp Crowder were scrapped. Soldiers and equipment from the Second Army that arrived from Fort Polk and Camp Beauregard, Louisiana, were soon on their way back to Louisiana because of the pipeline problem. Camp Crowder was turned over to the Signal Corps except for space for four Engineer regiments. Over 352 new buildings were initially built at the camp, but that was not enough and soon more construction was needed.

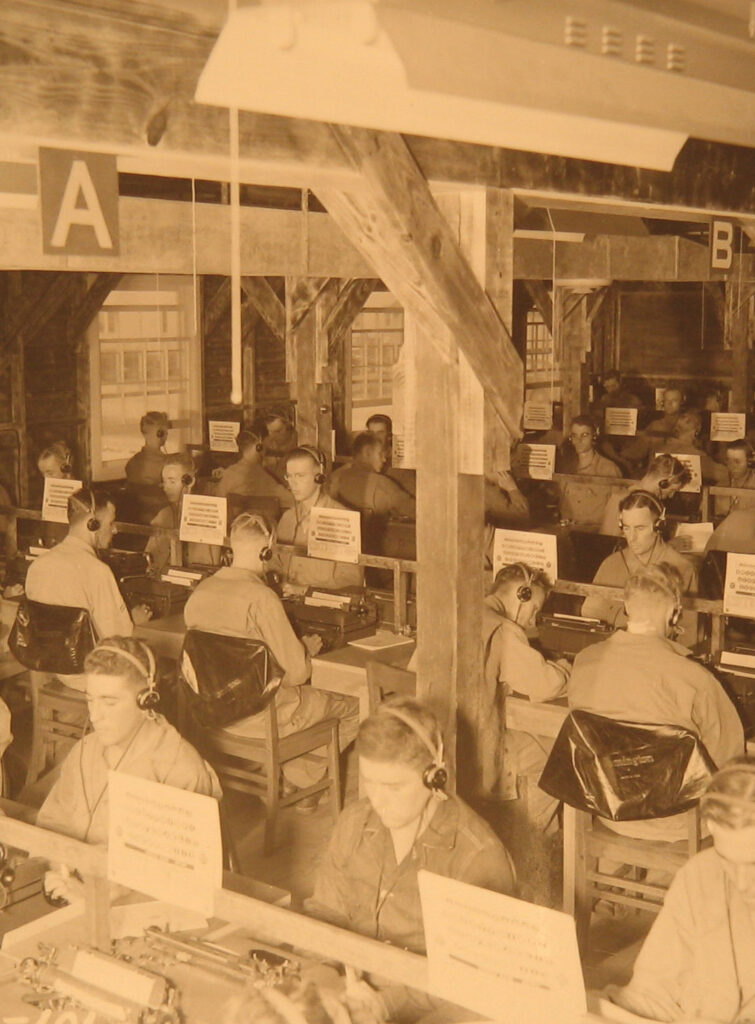

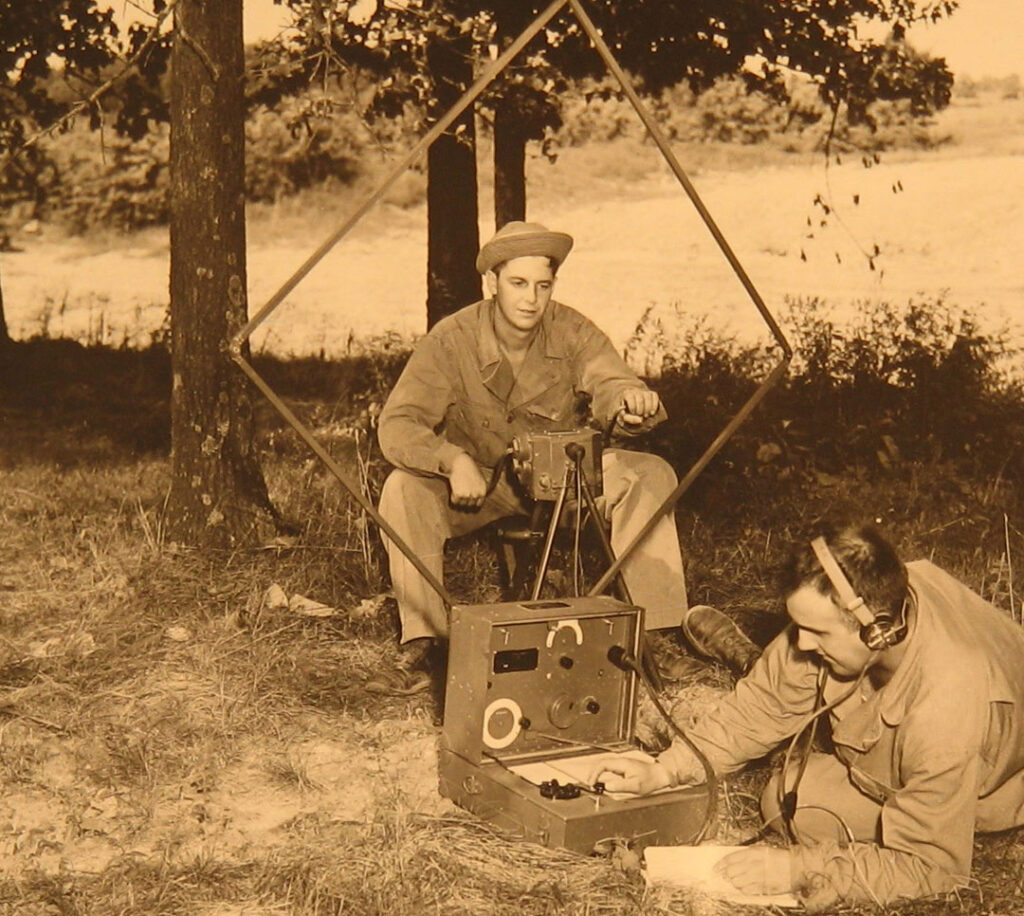

Camp Crowder received most of the Army’s signal recruits, each of whom spent three weeks learning the basics of soldiering: drill; equipment, clothing, and tent pitching; first aid; defense against chemical attack; articles of war; basic signal communication; interior guard duty; military discipline; and rifle marksmanship. Initially, Camp Crowder was named the Camp Crowder Replacement Training Center. In July 1942, the Midwestern Signal Corps School opened its doors at Camp Crowder with a capacity of 6,000 students. The following month, the Signal Corps’ first unit training center also opened there. The headquarters established in October 1942 to administer this group of schools was designated the Central Signal Corps Training Center. The 800th Signal Training Regiment was located at Camp Crowder in the 1940’s. This unit provided technical training in radio operations, radio repair, high power station operation and maintenance.

By 1943, the War Department had acquired a total of 42,786.41 acres of land in Newton and McDonald Counties that made up Camp Crowder. In order to establish this camp, major improvements had to be made in roads, utilities, railroad spurs, sewage system, and numerous buildings including barracks, mess halls and training facilities. It’s hard to imagine a post the size of Crowder. The Post Exchange had twenty-two branches, with three beauty parlors for WACs and female civilian employees. The post also had two cafeterias for civilian workers. Camp Crowder had its own post newspaper called the Camp Crowder Message with a circulation of 15,000. There were also four service clubs on post along with guest houses for soldier’s guests.

Crowder had six movie theaters on post. There were sixteen chapels with a chaplain for each providing regular Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, and Christian Science services. The American Red Cross office was staffed with a field director and seven assistant directors. There were USO Centers in the nearby towns. Camp Crowder had its own large well-staffed hospital and in addition had 15 infirmaries throughout the camp and three dental clinics. There was a field house for athletic events and other activities that could seat 5,000 persons. The post laundry accommodated officer and enlisted personnel and was one of the largest laundries in the country. Enlisted personnel paid $1.50 a month for laundry.

After some initial shunning of soldiers from the camp, civilians in the surrounding communities took an interest in the soldiers at the camp. On many Sundays, soldiers were allowed to leave post to attend church and have Sunday dinner with families in the area. On post, the men formed athletic teams, had visits from celebrities who came as part of USO shows or just to stop off and greet the soldiers. Most of the soldiers who were trained at Camp Crowder went overseas, serving in both the European and Pacific theaters.

Camp Crowder activated signal units by the hundreds—not only signal companies and battalions for operations and construction missions, but also new and previously unheard-of types of units, such as aircraft-warning companies and battalions (for radar-warning services to the Army Air Forces). Crowder also activated a numerous radio-intelligence and signal information and monitoring (SIAM) companies to support the Signal Corps’ large radio security and intelligence responsibilities. Then there were JASCOs—(Joint-Assault Signal Companies)—units created to meet the amphibious-assault communications needs of joint Army/Navy operations. Force structure requirements were so pressing, and often arose so suddenly, that students were taken out of the schools, their course work incomplete, to fill requirements in new signal companies and battalions.

One totally unrelated mission besides signal training at Crowder was the training of band personnel. On 24 July 1943, two band training units were established by order of Army Service Forces Commander LTG Brehon Somervell. One was located at the Quartermaster Replacement Training Center, Camp Lee, Virginia, the he second at the Signal Corps Replacement Training Center, Camp Crowder. This training was intended only to orient qualified draftees on the mission and operation of an Army band. It did not include any courses designed to increase the individual’s instrumental proficiency. When it became apparent that the Camp Lee Training Center could handle the entire music program, the Camp Crowder training unit was discontinued in 1944.

The beginning of World War II found the Army’s pigeon center located at Fort Monmouth where it had been since 1919. The Chief Signal Officer relocated the Pigeon Breeding and Training Center from Fort Monmouth to Camp Crowder in October 1942. This center, including its veterinary personnel which had just joined, moved to Camp Crowder where it remained until after V-J Day, when it was reestablished at Fort Monmouth.

Camp Crowder also housed some 2,000 Axis POWs. The first prisoners arrived on 6 October 1943 and had been captured from Rommel’s forces in North Africa. Most of the prisoners were repatriated by the end of 1946.

Cartoonist and Beetle Bailey creator Mort Walker was stationed at Camp Crowder during World War II. The camp served as the inspiration for the fictional “Camp Swampy” in his long-running comic strip, which began in 1950. Hollywood actor Dick Van Dyke was stationed at Camp Crowder during the war as well, inspiring fictionalized events portrayed in Episode No. 6 of The Dick Van Dyke Show, “Harrison B. Harding of Camp Crowder, Mo.,” that aired on 6 November 1961 on CBS. Actor and producer Carl Reiner who served in the Army with MAJ Maurice Evans’ Special Services unit during 1942-46, also spent part of his World War II days at Camp Crowder.

With the end of the war in 1945, activities at Camp Crowder began to wind down. In 1946, the camp was closed as a basic training site. For a short time, the camp was active as soldiers came there to be mustered out of the service. The impact of Camp Crowder’s establishment can only be matched by the impact of its closure. The millions of dollars spent locally by the government and soldiers almost disappeared entirely when World War II ended. In 1947, 29,407.633 acres of land was declared excess and sold to the public for agricultural use. The Missouri National Guard retained 4,358.09 acres for a training area.

Despite efforts to keep the camp active, Camp Crowder was never the same as it had been in World War II. During the Korean Conflict, the camp saw a slight rise in activity. Missouri already had Fort Leonard Wood, and there seemed to be little need for two active Army training facilities in the state. Crowder’s mission changed again in 1953 when it became a branch of the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks, remaining there until it closed in 1958.

Sometime during 1956, the Army transferred a portion of Camp Crowder to the Air Force for construction of a rocket engine manufacturing plant known as Air Force Plant No. 65. Construction of Plant 65 began in 1956, with operation beginning in 1957. For sixteen years, the Air Force tested engines for the Atlas, Thor, and Saturn rockets at Plant 65. In more recent years, Teledyne Industries and Sabreliner Corporation have used the facility to overhaul and test jet engines.

Most of Fort Crowder was disestablished in 1958 and declared surplus property in 1962. Eventually the Army moved out and the land was either returned to those farmers who had given up land for the camp or turned over to other government entities. Later, Crowder College was formed in 1963 and moved on to a portion of land where the Army had moved out. The college still uses some of the buildings constructed for military use in the early 1940s.

Today, the camp has seen a remarkable rebound as a training site for members of the National Guard. The Missouri National Guard’s deployment for the Global War on Terrorism has been so large that its activated troops could not all be mobilized at Fort Leonard Wood, necessitating the use of Camp Crowder. Between 150 and 200 members of the 1438th Engineer Company, based in Rolla, were the first troops since World War II to conduct mobilization exercises at Camp Crowder. Over fifty company-sized National Guard, active, and Army Reserve units have used Crowder for various purposes such as weapons qualification, engineer equipment training, and field combat exercises. In addition, Marine Corps Reserve personnel also currently use Camp Crowder for training purposes.