By Paul Morando, Chief of Exhibits, National Museum of the United States Army

On 7 June 2025, the National Museum of the United States Army will open a landmark exhibit on the Revolutionary War. As the U.S. Army and the nation enters 250 years of existence, commemorative events have already begun at battlefields, museums, and historic sites. Historic locations like Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, Valley Forge, and Yorktown still hold meaning and resonate with the American public. Of course, key figures like George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton will continue to be studied to understand their roles in forming the United States.

Historians, keen on capitalizing on the 250th anniversary, will publish timely books on the American Revolution and the politics that surround it. The media will look at our current situation and make connections to the past to define or redefine who we are as a nation. In addition, documentaries will try to capture the sights and sounds of the eighteenth-century through dramatic reenactments and powerful testimonies. However, what should not be overlooked in this commemorative period, is the role of the U.S. Army and the common Soldier.

The National Army Museum’s new special exhibition, Call to Arms: The Soldier and the Revolutionary War, uncovers the daily life of a Soldier and how our nation was formed through their service and sacrifice. It explores what motivated citizens to join the Continental Army. Visitors will gain a better understanding of why Soldiers fought and what were they fighting for.

(National Museum of the United States Army)

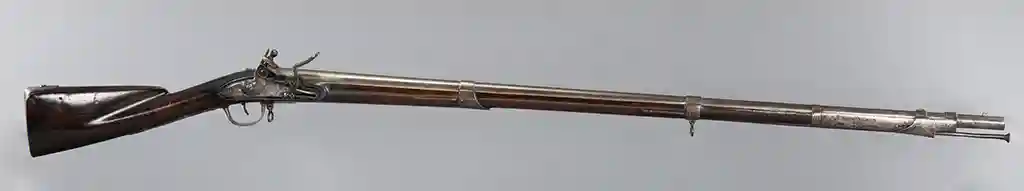

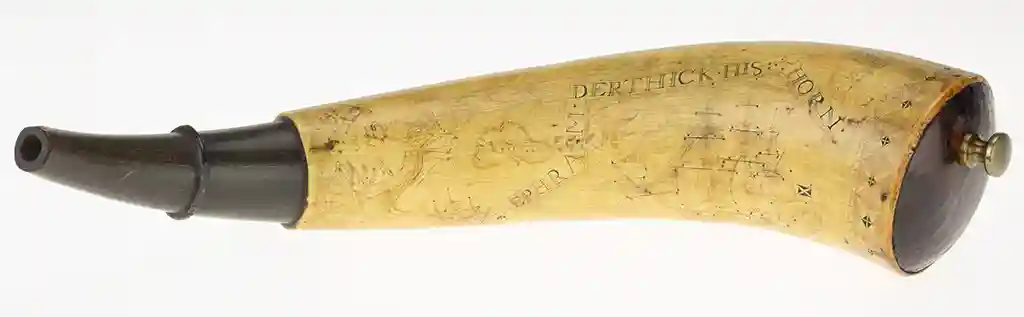

The exhibit features a rare collection of artifacts, some that have never been on public display. For example, visitors will see a flag carried at Yorktown, a powder horn carved at Valley Forge, a sword used at the Battle of Trenton, and a cannon fired at the Battle of Saratoga. In addition, visitors can read personal accounts such as an application by a widow seeking her husband’s pension, thirty years after the war ended, learn about lesser-known stories of those who served.

The exhibit will also showcase several international artifacts on loan from England, France, and Canada—with many of these objects being on display in the United States for the very first time. These significant objects provide further insight on the British Army, Loyalists, and France’s support of the United States.

While the Army has a rich collection of eighteenth-century material, the Museum relied heavily on partnering with historical organizations, museums, and collectors to bring in artifact loans to fill the 5,000-square-foot exhibit. These key relationships were crucial in developing the exhibit’s storyline that focused on the Soldier experience. Without their support, this exhibit would not exist.

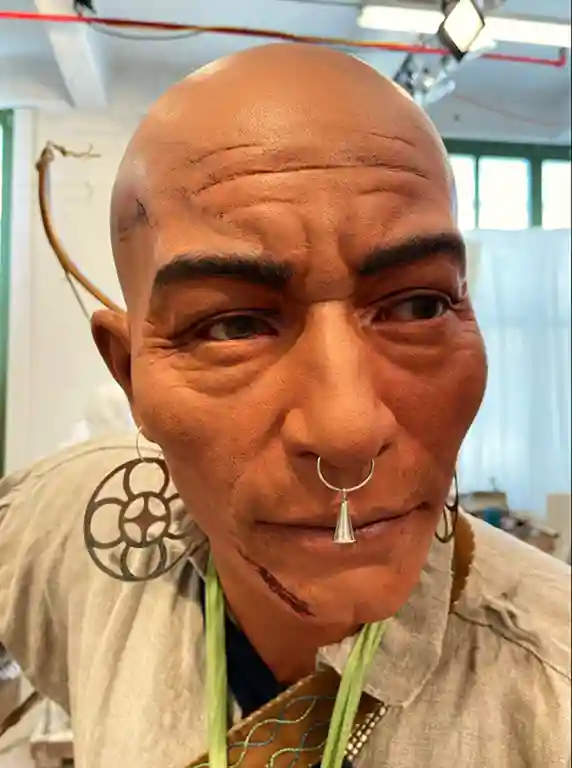

Beyond the artifacts, the exhibit also features realistic cast figures representing specific people who served in the war. For example, a cast figure of Daniel Nimham, chief of the Wappinger People, will be on display. Nimham joined the Patriots and fought at the Battle of Kingsbridge, where he was killed along with his son, Abraham. His story, along with interactive kiosks and projection maps, provides alternate ways for visitors to learn. Another opportunity for visitors to interact is a simple flip book where visitors can learn more about the important roles of people who served as teamsters, sutlers, and sappers. Teamsters or “wagoners” were vital as they helped transport essential supplies such as food, equipment, and ammunition to the Continental Army. Sappers, known today as combat engineers, were responsible for digging trenches and other field fortifications.

of the United States Army)

It is also important to note the different type of Soldiers that were fighting in the war. Early on, colonial North America had relied on militia units at the local level for armed defense. During the eighteenth century, militia units were as much about novelty as military capability. Most units trained once a month and saw no action. Cherry-picked men from these units served as minutemen, a selected group of militia who trained weekly and were expected to be the first response against an enemy threat. This dynamic was reinforced by the mythos of the citizen-soldier of Greek and Roman histories: the farmer who leaves home to defend the countryside. Militia units comprised a provincial army, or one made up of militia called by colonial governors and legislative bodies of government. The “Army of Observation” is another term applied to these assembled units, and other militia units raised at the local level. Some modern historians apply “Provincial Army” to the several bodies of assembled militia outside Boston in May-June 1775 prior to the establishment of the Continental Army on 14 June. The term was interchangeably used to describe militia units from a specific area.

When the Continental Congress created the Continental Army, George Washington, who Congress appointed as the Army’s Commander-in-Chief on 15 June 1775, understood the importance of a standing army. Success had to be a shared sacrifice, not one based on New England localism. As the war progressed, the Continental Army was comprised of both Continental Soldiers and militia. Continental troops were under the direct authority of both Congress and General Washington. These Soldiers enlisted for longer durations, received regular drill training, and typically saw the most combat. Militia units were in supportive roles that helped enlarge the Continental Army. Despite Washington having final authority in military command, militia units, as state troops, were under the direct authority of their respective states. Beginning in 1777 under the Third Establishment, individual states were required by Congress to produce Soldiers for the Army based on population percentages. Militia Soldiers volunteered or enlisted for shorter durations, and did not always receive the same drill training as Soldiers in the Continental Army. Some militia units were folded into the Continental Army while others served as separate attached units. Militia were less effective in European linear warfare and far more adaptable to irregular combat, though their unreliability in both training and long-term commitment repeatedly plagued Washington’s need for a sustainable, veteran-centered Army. It was not uncommon for Soldiers who served in a Continental regiment or a militia unit to reenlist or volunteer in the other once their enlistment expired in the former. Some American commanders learned to effectively use militia as auxiliary troops in battle.

The exhibit’s timeline is largely driven by the battles that Soldiers fought in. While emphasis is placed on significant American victories, the exhibit also reveals crucial losses. This illustrates the Continental Army’s resolve. Despite a propensity for offensive action, General Washington had to accept a strategy of carefully avoiding the potential annihilation of the Army. In many respects, the Revolutionary War was won by the Army staying intact. Keep the Army alive, keep the Revolution alive.

One instance that stands out is the escape from Brooklyn on 27 August 1776 during the Battle of Long Island. This was the first real test of the newly formed Continental Army. Up against British regulars and professional Hessian soldiers, the Americans were soundly defeated. As the American lines broke and retreated to Brooklyn, a last stand was made by Major General William Alexander. Known as Lord Stirling, he and nearly 300 troops from Maryland and Delaware held off 2,000 British regulars allowing the rest of the Continental Army to escape. Stirling was captured, but several observers agreed that “he fought like a wolf.” The American cause was nearly lost that day, quite possibly ending the Revolution.

While General Washington was fighting (and escaping) from the British, he was also addressing internal issues within the Army. This included desertion, low morale, lack of discipline, and inadequate supplies. There are many accounts of Soldiers initially joining the Army, returning to their families, and then rejoining the ranks based on how the war was going. As the war ebbed and flowed, so did the zeal for joining the Army. Thus, one of the major themes of the exhibit explores the motivations of Soldiers. Upon the establishment of the Army, the immediate challenge was to find a cohesive way to organize, enlist, and discipline Soldiers under a unified command. A year later, on 4 July 1776, Congress ratified the Declaration of Independence, affirming the colonies as free and independent states. While Congress declared independence, it was now up to the Army and its Soldiers to fight for it.

During this time, Soldiers were motivated by patriotism, religious faith, and service to their local community. They also served to escape rural life, for money, or because their friends and family did. They did not know how much they would sacrifice. A passion for arms or rage militaire inspired colonists to become Soldiers. Major Benjamin Tallmadge captured this spirit by stating, “The whole country seemed to be electrified. Among others, I caught the flame which was thus spreading from breast to breast.”

At times, their confidence masked their inexperience in battle. However, Americans fighting together forged something new: a national identity. This identity would continue to be defined as the war progressed. While many were still zealous for the cause of liberty, this was not enough to keep the fight up. Since many Soldiers were poor, Congress used bounties and postwar land grants to entice them to continue to serve. Some men saw prospects in the Army and hoped for better lives after the war. As the war dragged on, Congress called on the states to draft men from the militia, which most states did.

By 1781, as the war entered its sixth year, enlistments for many Soldiers began to expire. Congress continued to have difficulty paying the Soldiers. Due to inflation, much of the currency was worthless. In anger and frustration, some men staged mutinies. Officers responded by enforcing strict rules to maintain order. Despite these challenges, men continued to enlist to protect their homes. News of American victories on the battlefield also helped to swell their ranks.

After tough fighting in the South at Camden, Cowpens, Guilford Courthouse, and many other battles, the final stand and defining moment for the Continental Army came Yorktown in Virginia. There, Washington’s Continentals, with extensive assistance from their French allies, trapped the British against the York River. On 19 October 1781, the British forces under General Charles Lord Cornwallis surrendered. Within the special exhibit, an innovative topographical map projection depicts the strategy of the combined American and French forces at Yorktown. A narrated film is played in tandem with the displayed troop movements and artillery forces digitally illustrated on the map.

Through it all it was the strength of the Army that persevered. From the cold and dreary conditions at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, to the miserable heat and humidity at Eutaw Springs, South Carolina, Soldiers forged ahead through great privation and misery. This is captured through a film behind the “Camp Life” display. It depicts Soldiers in camp, building huts and foraging for food, and passing the time with daily activities to counter the humdrum life of a Soldier. More importantly, it also reveals the need for strict training and discipline instilled by General Washington under the guidance of Major General Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben.

Call To Arms concludes by turning to our nation’s first veterans and their plight to be compensated for their service. By today’s standards, Revolutionary War veterans were not taken care of immediately after the war. They were not recognized for their service with grand parades and accolades. As Soldiers returned home, many faced a harsh reality. While officers and invalids received some financial support, most enlisted veterans did not. It was not until after veterans of the War of 1812 received pensions that veterans and advocates for the Revolutionary War generation petitioned Congress. By then, many had either died or no longer had their discharge papers. Thus, filing claims for compensation extended to widows and children of veterans.

The experiences these Soldiers shared created a strong bond that endures today. They began a tradition of valor and sacrifice. They joined up in a time of crisis to defend their homes and liberty. After victory, they returned home or made new ones in the nation they helped create. For 250 years, American Soldiers have followed in their footsteps.

As the United States begins its commemorative season and recognizing the creation of the Army on 14 June 1775, this exhibit sets out to remind the American public the service and sacrifice of our original Soldiers. The museum will also produce complimentary educational programming over the two-year commemoration to document the major milestones of the revolution.

A tremendous amount of time and energy has been spent on research, writing, and collecting artifacts to produce this once in a lifetime exhibit. The artifacts and stories found within this exhibit are authentic. They represent the real experiences of Soldiers and the role the Army played in securing our independence and creating a national identity.

When Call to Arms closes in June 2027, the loaned artifacts will be returned, and the displays will be taken down. However, the lasting impressions of the exhibit will remain—of how the Army fought and won our independence with the continued hope of preserving our freedom for another 250 years.