By Matthew J. Seelinger, Chief Historian

Following the acquisition of the Philippines from Spain after the Spanish-American War, the United States became embroiled in a bloody and increasingly frustrating and unpopular campaign against Filipino insurgents. Many of the Filipinos initially welcomed the Americans as liberators and had expected independence once the American forces defeated Spain. Instead, the U.S. government decided to annex the Philippines. On 4 February 1899, two days before the Senate ratified the annexation treaty, Filipino soldier were fired upon by a U.S. sentry in Manila, opening what became known as the Philippine Insurrection.

At first, the U.S. Army found the poorly armed and organized rebels no match and repeatedly beat them in battle. Finally realizing that they could not defeat the Americans in conventional, set-piece battles, the insurrectos discarded their ragged uniforms, blended into the general population, and adopted guerrilla tactics. The Americans were largely unprepared for this change in tactics. The insurrection became a series of ambushes, reprisals, and patrol actions in the jungles. American soldiers who fell into rebel hands faced various hardships, including torture and murder. In retaliation, American troops would sometimes destroy suspect villages.

The insurrection would eventually take a heavy toll on American troops, as well as Filipino guerillas and civilians. By the time the rebellion was suppressed in 1902, over 6,000 American soldiers were killed or wounded, a figure that far exceeded the casualties of the Spanish-American War. Filipino losses were estimated at over 16,000. Furthermore, as the insurrection raged on, many Americans became vehemently opposed to U.S. involvement in the Philippines and America’s drift towards imperialism. For the U.S., the rebellion in the Philippines became the most divisive conflict in U.S. history between the Civil War and Vietnam.

Yet, despite the unpopularity and divisiveness of the conflict, the insurrection featured one of the most daring exploits in U.S. Army history. In an extremely risky mission, a small force of American soldiers, disguised as prisoners of war, ventured deep into enemy territory and captured Emilio Aguinaldo, the elusive rebel leader and self-proclaimed President of the Philippine Republic, in March 1901. With Aguinaldo captured, the rebels lacked the necessary leadership to successfully continue the struggle against the Americans, and, for all intents and purposes, the insurrection was finished.

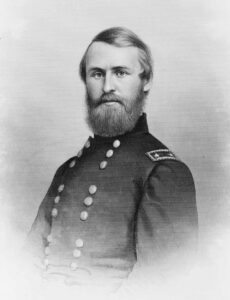

The mission to capture Aguinaldo was devised and led by BG Frederick C. Funston, a general in the Volunteers, who had already had a distinguished, and somewhat colorful, military and civilian life. He was born in Ohio in 1865 and raised in Kansas. After attending University of Kansas (he never graduated), he landed a series of jobs, including newspaper reporter, coffee planter in Central America, and special agent of the Department of Agriculture. This last assignment took him to such places as Death Valley and Alaska, where he made a 1,500 mile canoe trip down the Yukon River.

While passing through New York City in early 1896, Funston volunteered to join the Cuban rebels fighting against Spain. Despite the fact that he had no experience with artillery, Funston enlisted as an artillery officer. After a few weeks in an attic with a small artillery piece and an instruction manual, Funston learned enough to qualify. In August 1896, he was smuggled into Cuba. In eighteen months, Funston fought in four major battles and many smaller engagements. He was wounded several times, once through the lungs, and had a horse fall on him, leaving him with a permanent limp. He was eventually promoted to lieutenant colonel. Funston’s experiences in Cuba taught him a great deal about tactics, but also provided him with the basic concepts regarding the strategy and tactics of guerilla warfare.

In 1898 Funston returned to Kansas to drum up support for the Cuban rebels. When the U.S. declared war on Spain, Funston was given command of the 20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry. His regiment was ordered to San Francisco for possible deployment to the Philippines. Funston, however, was ordered to Tampa to be debriefed by MG William R. Shafter, who commanded the American forces assembled for the invasion of Cuba. Upon arriving in Tampa, Funston received a chilly reception from Regular Army officers, particularly Shafter, who viewed Funston as more of a roughneck adventurer than a soldier, and who generally dismissed the effectiveness of the Volunteers.

Funston and the 20th Kansas eventually shipped out to the Philippines, but they did not arrive until 30 November 1898, long after hostilities had ceased. Funston and his men anticipated a couple of months of occupation duty around Manila before returning home.

The outbreak of open rebellion by the Filipinos, under the leadership of the disgruntled Emilio Aguinaldo, changed Funston’s plans. In the early campaigns against the insurrectionists, Funston distinguished himself in several battles. On 27 April 1899, Funston’s bravery at the Battle of Calumet earned him a Medal of Honor. He was subsequently promoted to brigadier general of Volunteers, partly because of a glowing recommendation by BG Arthur MacArthur.

When the Volunteers were mustered out in September 1899, Funston came home with his unit but returned in December. Funston was assigned to command the 4th District of Luzon. By late 1899, conventional warfare had given way to guerrilla operations. Drawing on his experiences in Cuba, Funston launched a successful counterinsurgency campaign against the Filipino rebels, destroying supplies, building an efficient intelligence system, and conducting constant patrols. Throughout 1900, Funston’s operations gradually reduced the strength of the guerrillas, but a small, elusive, hardcore, group, centered on Aguinaldo, remained at large. Until Aguinaldo and his officers were eliminated, the insurrection would continue. The situation forced Funston to resort to drastic measures.

The intelligence break that led to the eventual capture of Aguinaldo came on 8 February 1901. While at his headquarters in San Isidro, Funston learned of the surrender of a small group of rebels in a nearby village. At first, the surrender of the insurgents did not draw much attention, as rebels deserted to the Americans on a fairly regular basis. Funston soon learned, however, that this particular group was commanded by Cecilio Segismundo, a trusted messenger of Aguinaldo. Even more important was the fact that Segismundo carried dispatches from Aguinaldo.

Realizing the potential importance of this development, Funston ordered Segismundo and the dispatches to his headquarters. Under questioning, Segismundo revealed that Aguinaldo could be found in his headquarters in the village of Palanan, located in the mountains of northern Luzon. In addition, he stated that Aguinaldo had no more than fifty guards in the village.

Uncertain whether Segismundo was telling the truth, Funston then examined the dispatches, which were in code. The messages were signed with the names “Pastor” and “Colon Magdalo,” code names often used by Aguinaldo. The handwriting used in the signatures was unmistakably Aguinaldo’s, so Funston and his staff quickly concluded that the dispatches were genuine.

With this information in hand, Funston and his staff began to formulate a plan for Aguinaldo’s capture. Funston first suggested landing a force near Palanan and marching overland to the rebel headquarters, but Segismundo warned him that any force landed in the vicinity would be quickly detected and provide Aguinaldo with plenty of time to flee.

Funston quickly devised an alternate plan. He decided to disguise a group of loyal Filipinos as the reinforcements Aguinaldo requested in his captured dispatches and send them to Palanan. Funston and a few other American officers, disguised as prisoners of war, would accompany them. The plan was submitted to the American headquarters and approved by BG MacArthur. While supporting Funston’s plan, MacArthur realized the extreme risks involved and worried for his friend’s safety. Later, as Funston and his party prepared to depart, MacArthur grabbed Funston’s hand and said, “Funston, this is a desperate undertaking. I fear that I shall never see you again.”

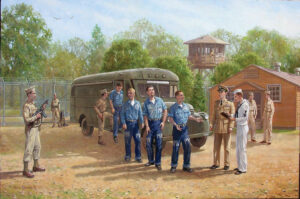

Funston’s plan called for disguising a small group of Macabebes, a Filipino tribe loyal to the Americans who also despised Aguinaldo’s Tagalogs, as insurgents and marching them with the “captured” Americans to Aguinaldo’s headquarters. The “Little Macs,” Funston’s nickname for the Macabebes, could also speak Tagalog in addition to their own dialect. They were equipped with captured rifles and dressed in peasant garb, since few rebels wore uniforms.

While Funston was actually in command of the column, it would appear to be under the command of Filipino officers. Funston recruited several Filipinos to pose as officers, including Segismundo, Hilario Tal Placido, Dionisio Bato, and Gregorio Cadhit. Placido had served as a rebel officer until he took an oath of loyalty to the U.S. and knew Aguinaldo personally. In addition to the Filipinos, Funston recruited Lazaro Segovia, a Spaniard who had helped decode the captured dispatches. To act as the American prisoners, who would pose as privates, Funston selected four officers, including his personal aide and first cousin 1LT Burton J. Mitchell, CPT Harry W. Newton, who was familiar with the Palanan area, and brothers CPT Russell T. Hazzard and 1LT Oliver P.M. Hazzard.

On the evening of 6 March 1901, the gunboat Vicksburg sailed out of Manila Bay with Funston and his party onboard. Upon reaching the landing point near the village of Casiguran on 12 March, Funston’s men were to paddle ashore in three small boats. Heavy seas, however, swamped the boats. To get the men ashore, the Vicksburg had to approach the beach at night. Fortunately, the landing went undetected, and by the morning of 14 March, with Vicksburg safely out to sea, Funston’s column set off for Casiguran.

After a short but difficult march, the column reached the village the following day. The villagers welcomed the “rebels”. While the column rested and gathered supplies for the trek to Palanan, Funston sent two forged messages to Aguinaldo. One, which appeared to have been sent by Placido, described the encounter that netted the American prisoners and stated that Placido was bringing them to headquarters for questioning. The other, allegedly from Urbano Lacuna, one of Aguinaldo’s subordinates, stated that in accordance with instructions from Baldomero Aguinaldo, he was sending eighty men to Palanan under the command of Placido, Segovia, and Segismundo. This second message was consistent with instructions contained in the captured messages decoded by Funston and his staff in San Insidro.

Several problems arose during the stopover in Casiguran. Funston heard that Palanan had been reinforced by 400 men. Despite the increased odds, Funston convinced his men that the element of surprise would compensate for the disparity in numbers. Another problem was that the villagers could only provide three days of rations, and it would take seven days to reach Aguinaldo. Because of their tight schedule (Vicksburg was scheduled to arrive in Palanan Bay on 25 March), Funston decided to continue on with what the column had on hand and supplement the rations with whatever they could. A third problem arose when Funston’s guide deserted during the first day out of Casiguran. Fortunately one of the Casiguran bearers knew the way to Palanan and the column pressed forward.

As Funston’s men marched on, their progress was greatly hampered by the poor weather and rough terrain. The men were allowed only two meals per day in order to stretch the rations. Just as Funston’s men had reached the limits of their endurance, Aguinaldo himself came to rescue. He had received the forged messages and had ordered his chief of staff, Simon Villa, to meet the column. Upon his arrival, Villa told the starving men that provisions would be arriving. There was some bad news, however, as Villa stated that the prisoners would kept in the village of Dinundungan. At the same time, Funston’s spirits were raised when he learned that the 400 men that were to reinforce Palanan never arrived.

That night, Funston put his forger’s skill to use again. He produced a letter stating that the prisoners were to be brought to Palanan. The message was to be carried back to the camp by one of the Little Macs and was to arrive an hour after the column departed for Aguinaldo’s headquarters. The next morning, the ruse went as planned, and Funston and the other Americans were sent up with ten Macabebes who had remained as guards.

As Funston and his men made their way to Palanan, they narrowly avoided a group of rebels sent to guard the prisoners in Dinundungan. In the meantime, the “rebel” officers of Funston’s column had crossed the rain-swollen Palanan River and made their way to Aguinaldo’s headquarters. Aguinaldo greeted Placido and Segovia and took them to his residence. Placido gave a long, time consuming account of the Filipinos’ victory over the Americans. At the same time, Segovia nervously watched the crossing of the rest of the column, hoping that the plan would not be betrayed before the force was across the river.

Once across, the Little Macs formed ranks and marched towards Aguinaldo’s guards. At the right moment, Segovia gave the signal by waving his hat and calling out to the men. In an instant, the Macabebes opened fire, killing two guards and scattering the rest.

Aguinaldo, thinking that the shots were intended as a salute to the newcomers, moved towards the window to order the guards to conserve their ammunition. As he did, Placido tackled him and wrestled him to the ground. At the same time, Segovia rushed back in from the balcony where he had given the signal. By then, Aguinaldo’s officers began to recover from their shock and started to draw their weapons. Segovia immediately fired six shots from his revolver, killing two rebels. The others quickly surrendered or jumped out the windows to escape.

Funston’s small group arrived at the river crossing just as the gunfire erupted and crossed quickly. Funston’s intervention spared several of Aguinaldo’s men from the Little Macs who were more than willing to fight it out with the rebels. Inside the headquarters, Funston found Aguinaldo pinned to the floor with the stocky Placido sitting on him. Aguinaldo quickly realized what had happened and meekly surrendered. Two of his chief officers were also taken prisoner.

With the mission almost over, Funston and his party rested and helped themselves to food left behind by the villagers who had fled when the shooting began. On the morning of 25 March, Funston’s column rendezvoused with Vicksburg in Palanan Bay and set sail for Manila.

During the trip to Manila, Aguinaldo admitted to Funston that he had been completely fooled by the phony dispatches. He later confided that he could “hardly believe myself to be a prisoner” and that he was gripped by a “feeling of disgust and despair for I had failed my people and my motherland.”

On 28 March, Vicksburg arrived in Manila Bay with Funston’s party and its three prisoners. The news of Aguinaldo’s capture was a cause for great excitement in Manila and across the U.S. By the spring of 1901, the American public had grown weary of a conflict that appeared to hold no promise for a conclusion. Funston’s actions provided hope that an end to the struggle was in sight. Yet Funston’s exploits also received condemnation by some that opposed American occupation of the Philippines. Some perceived Funston’s methods as treacherous and underhanded. Mark Twain, who wrote a sarcastic diatribe entitled “In Defense of General Funston,” took issue with Funston’s “begging for food then capturing his benefactor.”

But despite the attacks on Funston, the fact remained that the capture of Aguinaldo was the most important development of the Philippine Insurrection. Without him, the rebellion had lost its center of gravity. On 19 April 1901, Aguinaldo issued a proclamation calling for the rebels to lay down their arms and accept American sovereignty. Not all did, but the insurrection had been greatly weakened. On 4 July 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed the Philippine Insurrection officially over. Despite the proclamation, fighting continued for several more years against the Muslim Moros in the southern Philippines.

For his daring expedition, Funston was recommended for brigadier in the Regular Army, which he received in December 1901. He later went on to distinguish himself by helping to restore order to San Francisco after the devastating 1906 earthquake. He served as military governor of Veracruz, Mexico, during the American occupation (21 April-25 November 1914). After receiving a second star on 17 November 1914, he was appointed Commander of the Southern Department, supervising Army operations along virtually the entire Mexican border. After Pancho Villa’s raid into New Mexico in 1916, Funston ordered BG John J. Pershing to lead an expedition into Mexico to apprehend him. In early 1917, with the possibility of American involvement in the war raging in Europe becoming more likely, it appeared that Funston would be named commander of any U.S. expeditionary force sent to Europe. This, however, was not to be. On 19 February 1917, while dining at a hotel in San Antonio, Funston suddenly collapsed and died of heart failure.

Few actions in the history of the U.S. Army can match the drama of Funston’s capture of Aguinaldo. Through skillful use of intelligence, sheer resourcefulness, and a tremendous amount of raw courage, Funston and his small party marched through the heart of enemy controlled territory and captured the leader of the Filipino insurrectionists in his own headquarters. While Funston would continue to distinguish himself throughout his Army career, he would always be best known for his daring exploits in the Philippines.

For more information on Frederick Funston and the capture of Emiliano Aguinaldo read: David Haward Bain, Sitting in Darkness: Americans in the Philippines; Brian McAllister Linn, The U.S. Army and Counterinsurgency in the Philippines War, 1899-1902; Frederick Funston, Memories of Two Wars: Cuban and Philippine Experiences; William Zornow, “Funston Captures Aguinaldo,” American Heritage (February 1958); and COL John B.B. Trussell, Jr., USA-Ret., “Frederick Funston: The Man Destiny Just Missed,” Military Review (June 1973).