Written By Eric Anderson

Historian Henry P. Johnston writes that the Battle of Stony Point was “…altogether the most brilliant performance of the [American] revolution.” Yet in most books about the conflict, the battle is only mentioned in passing, if mentioned at all, its importance overshadowed by larger actions such as Saratoga, Monmouth, and Yorktown. Indeed, compared to those battles, it was a minor engagement, but its repercussions played a crucial role in keeping the American cause alive. Johnston elaborates, “It taught the enemy that the ‘rebels’ could use the bayonet with a boldness and effect which even their own infantry could not easily surpass; it increased the confidence of the American troops at large in their own prowess; it was, in fact, one of those events in war which count for much, and which in our Revolutionary struggle especially had important influence in bringing it to a successful termination.”

By the summer of 1779, the American Revolution had reached its fourth year, and despite many battles, the contest remained a stalemate. The previous year, France had formally allied itself with the rebellious colonies and the Continental Army, which had suffered several crushing defeats early in the war but seemed to finally be experiencing a change in fortune. Whipped into shape by Major General Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben during the winter of 1777-78, it had gone from little more than a ragtag assemblage of state militias to a professional army. However, despite these advances, the American cause remained a precarious one. The colonies were suffering from rapid inflation while Congress, seemingly complacent, was busying itself with trivial matters. General George Washington, commanding general of the Continental Army, wrote to a friend in Virginia and had this to say of the situation:

If I were called upon to draw a picture of the times and of the men from what I have seen, heard, and in part know, I should in one word say that idleness, dissipation, and extravagance seem to have laid fast hold of most of them; that speculation, peculation, and an insatiable thirst for riches seem to have got the better of every other consideration and almost of every order of men; that party disputes and personal quarrels are the great business of the day; whilst the momentous concerns of an empire, a great and accumulating debt, ruined finances, depreciated money and want of credit, which in its consequences, is want of everything, are but secondary considerations and postponed from day to day, from week to week…

The situation of the British Army was equally tenuous. Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton’s orders were to draw Washington into a full-scale engagement and win a decisive victory. This, however, was no easy task; waiting upon sufficient reinforcements, which he had been promised earlier that year, he had little flexibility to achieve this goal. Clinton’s predicament is best summed up in his own words: “If reinforcements do not arrive soon for sea and land I dread consequences. Not a word from Europe these three months, not a farthing of money, no information, no army, nothing but good spirits and a presentiment that all will go well, a determination at least that nothing shall be wanting on my part; and I sincerely hope that this will be the last campaign of the war—it must be mine.”

In late May, Clinton marched his army of 6,000 men out of its winter quarters in New York. He hoped to lure Washington into battle by threatening West Point, where American fortifications guarded essential lines of communication between New England and the middle colonies. He first captured the small American fortifications at Stony Point and Verplanck’s Point, which guarded Kings Ferry on opposite shores of the Hudson, on 31 May and 1 June, respectively. Kings Ferry, while not vital, was the most convenient route of communication and supply between the colonies, and Clinton hoped this would be enough of an incentive to draw Washington into battle. Meanwhile, Washington, sensing the danger, quickly marched his army out of its winter encampment at Middle Brook, New Jersey, to a strong defensive position between the British Army and West Point at Smith’s Clove. Clinton, not willing to risk marching farther toward West Point without the promised reinforcements, kept his army at Kings Ferry, hoping Washington might come to him. Washington, however, did not take the bait. After spending most of June waiting for his promised reinforcements and finally despairing of any hope of their arrival, Clinton withdrew his army from Kings Ferry to the vicinity of Phillipsburg (now Yonkers), New York, leaving small detachments to garrison the two forts.

While Washington was unwilling to give up his strong position, he was concerned about the effects of his inactivity. He knew that something must be done to maintain confidence in the Continental Army and the American cause in general. Worried over the inept Congress and the current rate of inflation, Washington hoped a victory could provide a much-needed boost to the morale of the fledgling nation. In consideration of these means, Washington ordered Major Henry Lee and his Partisan Legion of several hundred men to begin reconnoitering the British positions at Stony Point on 6 June. If Stony Point was retaken, the guns atop its heights could be turned against Verplanck’s Point, which lay at a lower elevation directly across the river. The British had employed similar tactics when they seized Stony Point several days earlier.

The initial reports Washington received were not favorable. Stony Point appeared to be well fortified. However, on 2 July, he received some encouraging news. Allan McLane, a daring young officer recently transferred to Lee’s Legion, had infiltrated the defenses of Stony Point and gained highly useful intelligence. Under the guise of a rustic backwoodsman, he escorted a Mrs. Smith (who wanted to visit her sons, presumably Loyalist soldiers, posted at Stony Point) into the fort under a flag of truce. By now the British had been building up the defenses of Stony Point for a month. The garrison declared it to be impregnable, referring to it as “Little Gibraltar.” Indeed, it was a strong natural position—a steep, rocky peninsula which protruded into the Hudson for half a mile and rose to a height of 150 feet. A marsh that flooded at high tide separated it from the mainland; the only means of reaching it was over an earthen causeway. The British cut down all the trees on Stony Point to create clear fields of fire and used the logs to create two separate lines of abatis spanning the peninsula. Behind the abatis, the British constructed breastworks. The main fortification rested on the plateau at the top of the point. Both the upper and lower works were strengthened by three artillery emplacements (or fleches in conventional military terminology of the time) each. There were also several other pieces of artillery located about the fortification, giving the British a total of fifteen guns at Stony Point. In addition, two British ships guarded the position’s northern and southern flanks along the river.

The works were manned by eight companies of the 17th Regiment of Foot, which had arrived in America in 1775 and were veterans of many of the major battles fought thus far; two companies of grenadiers from the 71st Regiment of Foot (Fraser’s Highlanders), another veteran regiment; sixty-nine men of the Loyal American Regiment, a regiment of Loyalists whose colonel lived twelve miles north of Stony Point; and a number of servants and artisans. In all, the garrison of Stony Point amounted to 564 men. In command of this formidable fortification was Lieutenant Colonel Henry Johnson of the 17th Regiment of Foot. An officer in the British Army since the age of thirteen, Johnson had eighteen years of military service under his belt.

All of these factors added up to make Stony Point an incredibly imposing stronghold, but it was not without weaknesses, which McLane quickly identified once inside. He observed that entrenchments within the inner fort were incomplete and that most of the artillery in the British position consisted of naval guns that would be difficult to maneuver during a fight. According to a later account by one of his men, as McLane discreetly surveyed the fort, a British officer took note of his seemingly innocuously rustic appearance and decided to partake in some playful derision. He asked McLane if he thought that their “fortress was strong enough to keep Mr. Washington out.” McLane responded by saying that as a woodsman he knew nothing of these matters, but that he guessed that Washington “would think twice before he would run his head against such works as these” and assured him “If I were a general, sure I am that I would not attempt to take it, though I had 50,000 men.” The officer then confidently stated, “If General Washington…should ever have the presumption to attempt it, he will come to rue his rashness, for this post is the Gibraltar of America, and defended by British valor, must be deemed impregnable.” McLane concurred, “No doubt, but trust me, we are not such dolts as to attempt impossibilities, so that as far as we are concerned, you may sleep in security.” Upon leaving the fort, McLane shrewdly reported its weaknesses to Lee and informed him that Stony Point could be taken.

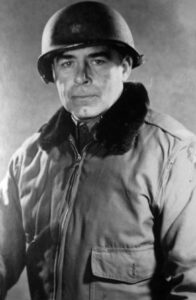

Once Washington knew that Stony Point was not the unassailable “Gibraltar” many thought it to be, he quickly jumped into action and began formulating a plan for its capture. On 6 July, he personally reconnoitered its works and, by 10 July, had devised a plan. Brigadier General Anthony Wayne was to lead the Light Infantry Corps, under the cover of darkness, in a surprise attack on the fortification. In order to ensure that the British did not detect their advance, the men would not be allowed to load their muskets; the storming of the works was to be done strictly with cold steel.

The Light Infantry Corps was ideally suited for this task. Recently assembled, it was the elite arm of the Continental Army, consisting of soldiers chosen on such factors as strength, bravery, and experience—in order to be chosen for the Light Corps, a soldier must have served in the Continental Army for at least one year. The officers of the corps were among the finest in the Army, all hand-picked by Washington. In addition to its exceptional personnel, the corps underwent extensive training in the use of the bayonet, under the tutelage of Major General von Steuben.

For such a dangerous undertaking, it was only natural that the audacious Wayne would lead the attack. A former surveyor and proprietor of a tannery, he joined the Continental Army as a colonel in 1775. By 1779, he was a battle-hardened veteran who had proven his courage on the battlefield time and again. For his actions at Monmouth Courthouse, he was lauded as a “modern Leonidas.” Wayne’s record clearly showed he was not one to shy away from a fight, and his aggressiveness in battle earned him the nickname “Mad Anthony.”

Meanwhile, Clinton, in another bid to draw Washington away from West Point, sent detachments of his army to plunder and burn several towns in Connecticut. These raids made Washington all the more eager to strike a blow. After several more days of studying, monitoring, and surveying Stony Point, Washington and Wayne decided to carry out the attack on the night of 15 July. The final plan of attack was drawn up by Wayne and sent to Washington on the morning before the attack was to take place. Washington trusted Wayne to make any changes to the original plan he thought necessary.

The plan of attack was multi-faceted. The main column, led by Wayne, would strike Stony Point’s southern flank; a second column, under Colonel Richard Butler, would hit the northern flank. A third diversionary column under Major Hardy Murfree was to attack the position’s center. This third column was permitted to carry loaded muskets because its mission was to fire on the fortification and draw out the British, buying time for the other two columns to cut through the abatis.

The columns moving on the position’s northern and southern flanks were to attack in three waves. A small group of twenty volunteers known as a “forlorn hope” (a term for a body of soldiers assigned a perilous mission) would advance ahead of the vanguard, clear a way through the abatis with axes, and subdue the sentries. The second wave, the vanguard, consisting of 100 men in the northern column and 150 in the southern, were to secure the breaches created by the forlorn hopes. Lastly, the main body of troops was to follow close behind and provide support. In addition, twenty-four artillerymen were to accompany the attacking columns to turn the enemy’s guns on Verplanck’s Point and the enemy ships patrolling the river. Once the fort was stormed, the men were to yell the watchword “The fort’s our own” to confuse the defenders and cause them to surrender. In all, Wayne’s force numbered around 1,150 men.

That same morning, Wayne assembled and reviewed his troops at Sandy Beach some fourteen miles from Stony Point. Until that day, the regiments of the Light Infantry Corps were camped in several different locations so as not to arouse suspicion about the impending attack. For similar reasons, most of the men had not yet been informed of their mission. After their inspection, they probably expected to break ranks and return to their camps; instead, they were ordered to march south. For much of the day, the soldiers marched through the mountains down a remote wilderness path, at times having to march single file due to the difficult nature of the terrain. Wayne, in keeping with the need for secrecy, sent patrols ahead of his main column to make sure their approach went undetected. Any civilians encountered along the way were detained.

The arduous march of Wayne’s force finally ended about 2000 when they arrived at the farm of David Springsteel, about a mile and a half from Stony Point. This would be the staging point for the attack. Wayne and his officers went on a final reconnaissance of Stony Point and, upon their return, the men were formed into columns and given their orders in hushed tones. The orders were sobering and reflected the importance of their mission, stating, “If any soldier presumes to take his musket from his shoulder, or to fire or begin the battle until ordered by his proper officer he shall be instantly put to death by the officer next to him; for the misconduct of one man is not to put the whole troops in danger or disorder, and be suffered to pass with life.” Wayne’s orders also contained the assurance, “The General has the fullest confidence in the bravery and fortitude of the corps that he has the happiness to command.” Wayne even offered a bounty of $500 and immediate promotion to the first man to enter the fort, as well as lesser bounties for the next four to enter behind him.

The attack was to commence at midnight. In the meantime, the men were left to anxiously contemplate their fate. Wayne took this time to write a friend in Philadelphia telling him to watch over his children in the event of his death. He wrote, “I am called to sup, but where to breakfast? Either within the enemies lines in triumph or in the other world!” White strips of paper were handed out for the soldiers to pin to their hats so that they could recognize friend from foe in the darkness. Indeed, the night of 15-16 June was extremely dark, as well as unseasonably cool and blustery.

Wayne’s troops moved out around 2330 and, by midnight, the three columns were in their respective positions, with Lee’s legion, Colonel Ball’s regiment, and Brigadier General Peter Muhlenberg’s brigade positioned in reserve in case the attack faltered. The marsh, which the columns attacking from the north and the south had to cross, was flooded by the tide, necessitating a delay. For twenty minutes, Wayne’s men waited under the ominous shadow of the rocky prominence, haunted by the lurking specter of their own doom. Finally, the tide receded enough for the men to wade through the marsh, and the attacking columns silently stepped forward.

As they neared the first line of abatis, pickets from the 71st Regiment detected the approach of either Murfree’s or Butler’s men near the northern neck of the peninsula and fired several shots in their direction. The dark, windy night, however, played to the Continental’s advantage. The lieutenant in charge of the pickets dismissed the attack as “wind rustling amongst the bushes.” Moments later, Murfree’s column began its diversionary attack, opening fire on the British center. The gunners in the southernmost battery in the outer works quickly responded by firing their 12-pounder cannon at the causeway crossing the swamp, which they had been ordered to do as a means of sounding the alarm in case of an enemy attack. The bright flashes of cannon fire revealed Wayne’s column advancing on Stony Point’s southern flank. The cannon, being confined to an embrasure, could not be turned on Wayne’s men, but the defenders did begin to fire upon them with their muskets. Despite this fire, Wayne’s men continued their advance. Wading around the first abatis, the forlorn hope under Lieutenant George Knox dashed up the slope and began hacking a path through the second abatis. Meanwhile Butler’s column, attacking from the north was taking heavy casualties. As its forlorn hope under Lieutenant James Gibbon was clearing the first line of abatis, the defenders blasted away at them with a 3-pounder cannon and musket fire. Undeterred, Butler’s column continued up the northern slope and rushed toward a gap the British had left in the second line of abatis. This gap was on a rocky area of the slope, known as the precipice, which the British thought was too difficult for an attacking force to navigate. Butler’s column proved them wrong.

On the southern slope, Wayne’s column broke through the second line of abatis and were streaming toward the main parapet. As Wayne himself passed through the second abatis, a musket ball grazed his skull, creating a two-inch-long laceration and causing blood to spill down his forehead. It is reputed that upon regaining his composure Wayne yelled, “Forward, my brave fellows, forward! Carry me into the fort. If I am to die, I want to die at the head of my column!” (Apparently his men thought better of moving their wounded leader, because according to later reports, he was not carried into the fort until after the fighting was over. He did, however, continue to direct their movements.) Lieutenant Colonel Francois de Fleury, a Frenchman commanding the vanguard of the southern column, was the first to enter the fort and, upon doing so, seized the British flag. The watchword “The fort’s our own!” was taken up by the jubilant Continentals, causing mass confusion among the defenders. Soon after Wayne’s column entered the main fort, Butler’s column clambered over its northern defenses.

The British garrison, however, continued to put up a stiff resistance, and a fierce hand-to-hand struggle ensued. Bayonets, spontoons, and swords were employed with deadly effect. The struggle within the fort lasted for another fifteen minutes before the British finally laid down their arms and surrendered. All who asked for quarter received it. It is to the credit of Wayne’s men that they showed their enemy a remarkable level of mercy, especially in light of the callous raids the British had recently carried out in Connecticut. Wayne commended his men’s compassion in his report to Washington, saying, “The humanity of our brave soldiery, who scorned to take the lives of a vanquished foe calling for mercy reflects the highest honor on them, and accounts for the few of the enemy killed on the occasion.” Even the British recognized the admirable conduct of their foe. Commodore George Collier stated, “The Rebels had made the attack with a bravery they had never before exhibited, and they showed at this moment a generosity and clemency which during the course of the rebellion had no parallel.”

The careful planning conducted by Washington, Wayne, and the officers under them paid off. Lieutenant Colonel Johnson played into the Americans’ trap perfectly. Upon hearing the demonstration by Murfree’s men, and believing it was the main assault force, he led six companies of the 17th Regiment out of the main fort, significantly weakening the garrison and leaving it vulnerable to Wayne’s flanking columns. Once Johnson heard the commotion in his rear and recognized his mistake, it was too late. He tried to lead his men back into the fort, but soon realized he was surrounded and surrendered. Additionally, the Royal Artillery had proven to be of little help, as most of their guns were naval pieces and too cumbersome to be wheeled about and quickly aimed at the swiftly-moving light infantry. According to later testimony, it was determined that only two of the fort’s fifteen guns were employed that night. Even the two ships assigned to guard the point were of no help. Due to the high winds, they had weighed anchor in the middle of the Hudson to avoid running aground. After the surrender of the fort, the American gunners who had accompanied the attacking columns turned the fort’s cannons on the enemy ships, forcing them to flee downriver. A feint attack was made on Verplanck’s Point as well, with a siege of the position planned for the following day. It was later abandoned in the face of a British advance.

During the assault, fifteen Americans were killed and another eighty-three wounded. The British suffered twenty killed, seventy-four wounded, fifty-eight missing, and 472 captured. Wayne’s men were well rewarded for their efforts, as Wayne ordered the money gained from the captured British supplies and equipment to be distributed among his men-—the value of the captured supplies came to over $160,000.

By 0200, Wayne had recovered enough from his wound to write a quick note to Washington: “Dear Gen’l: The fort and Garrison with Col. Johnston are ours. Our officers and men behaved like men who are determined to be free.” Washington arrived the next day to congratulate those who had participated in the attack and examine the works. He determined that he did not have a sufficient number of men to man them, so he ordered them destroyed and abandoned the position.

At first glance, it seems that the Battle of Stony Point achieved little, but this presumption is contrary to the truth. The victory stifled any plans Clinton had for another offensive; instead his efforts were concentrated on refortifying Stony Point. Furthermore, the American victory had repercussions that far exceeded military gains. Through it, confidence and hope in the American cause were kept strong. The prominent patriot Dr. Benjamin Rush later wrote a letter to Wayne, declaring, “…our streets, for many days, rang with nothing but the name of General Wayne,” adding, “You have established the national character of our country; you have taught our enemies that bravery, humanity, and magnanimity, are the national virtues of the Americans.” Congress shared Rush’s sentiments and granted medals to three of the participants: Wayne, de Fleury, and Major John Stewart. Only eleven such medals were granted during the Revolutionary War.

The Battle of Stony Point had a profound effect on British morale as well. Soon after, a depressed Lieutenant General Clinton wrote to an aide, stating, “Let me advise you never to take command of an army. I know I am hated, nay detested, by this army….” Stony Point was the final nail in the coffin in British efforts to conquer the Northern and Middle colonies; the next year, Clinton moved his focus to the Southern colonies hoping to find more luck there.

It is important that the Battle of Stony Point be remembered, if not for its historical importance then to honor the bravery, sacrifice, and humanity of its participants. In the same letter mentioned earlier, Dr. Rush wrote to Anthony Wayne, “…When our little ones are able to repeat your name, we shall not fail to tell them in recounting the exploits of our American Hero’s how much they are indebted to you for their freedom and happiness.” These same sentiments can be applied to all those brave men who charged up Stony Point’s precipitous slopes in July 1779.