By William Dennis

Hitler’s goal in the December 1944 German counteroffensive through the Ardennes in southern Belgium and Luxembourg was to break through the American lines and take control of roads that would allow the Wehrmacht to drive to the port city of Antwerp. The salient would leave the bulk of the U.S. forces on one side, the British on the other, and perhaps lead to a negotiated peace with the western Allies. The Schwerpunkt, the main effort, was the Sixth Panzer Army’s attack on the sector of the American line held by the 99th Infantry Division.1

The German commanders fully expected their attack in what became known as the Battle of the Bulge would at least rupture the American lines. Colonel Graf Friedrich von der Heydte commanded a parachute unit tasked with dropping behind American lines to prevent reinforcements from the north. Sixth Army’s commander, General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, told him that the American lines “were held by a couple of bank managers and Jew boys.” 2

area of the Krinkelter Woods in Belgium, 15 December 1944. On the following day, the Wehrmacht launched

its counteroffensive in the Ardennes, marking the opening of the Ardennes-Alsace Campaign, better known as the Battle of the Bulge. (National Archives)

Sixth Panzer Army’s failure to fully break through the American lines in the area that became known as the “north shoulder” of the Bulge doomed the German plan. Two American infantry divisions, with considerable help from supporting units, held off the attack of a much larger German force until reinforcements arrived. That force was the best-trained and equipped army that Germany could field at this stage of the war.

Originally, Bastogne was on the southern periphery of Sixth Panzer Army’s sector.3 The Fifth Panzer Army, commanded by General Hasso von Manteuffel, and Seventh Army, commanded by General Erich Brandenberger, were tasked with protecting the Sixth’s left flank.

The Wehrmacht needed to break through quickly before the Allies understood the scope of the German attack and brought more of its fast-moving armored and mechanized infantry units into the fight. The stubborn resistance of the American troops in the north shoulder blunted Sixth Army’s advance so quickly that the Kampgruppen from its panzer divisions and much of the army’s remaining strength were committed. It never achieved a breakthrough. Fifth Panzer Army, advancing to the south, broke through the American lines and later became the main striking force and the axis of attack as it shifted toward Bastogne.

The Sixth’s I Panzer Corps, which made the main attack, included the 1st and 12th SS Panzer divisions, the 12th and 277th Volksgrenadier Divisions, and the 3d Luftwaffe Parachute Division. Its assault echelon included the Volksgrenadiers, Luftwaffe troops, and Kampgruppen (task forces) from several panzer divisions. They were to mount frontal attacks and bludgeon a way through the American lines.

On paper, the Germans appeared to have employed enough strength to have rolled over the extended lines of the inexperienced 99th. Germany, however, was sending poorly trained and equipped troops to face a division that was well-trained and whose ranks contained many exceptional young men.7 Furthermore, the terrain in the area was not particularly well suited for the operation the Germans envisioned, and several of America’s best divisions were either on hand or quickly available.8

As the Battle of the Bulge opened, the 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron (Mechanized) held a sector around Monschau. To the south, 3d Battalion, 395th Infantry Regiment (3-395 IN), held the town of Höffen. South of Höffen was an undefended area of dense, roadless forest that ended near the Wahlerscheid station. Except for a small sector around Wahlerscheid, the rest of the 99th Division held the front south to where the 14th Cavalry Group screened the Losheim Gap, a historic invasion route. The center was held by the 393d Infantry Regiment; the 394th Infantry held the south end of the division sector. The Intelligence and Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon of the 394th manned an outpost that overlooked the town of Losheim. 3d Battalion, 394th Infantry Regiment (3-394 IN), was located around Buchholz station as division reserve.

The 99th Division held nineteen miles of front.9 As a result, its front line consisted of a string of platoon-sized strongpoints too far apart to provide mutual support.10 Except around Höffen, these positions were mostly within dense forest. The attacking Germans often got within the limited range of the machine pistols that many of them carried before the Americans could take them under fire, negating some of the advantage of the American weapons.11 The attackers had a great numerical superiority.12

The veteran 2d Infantry Division was assigned a small sector opposite the Wahlerscheid station to use as a springboard for an attack on the German West Wall border fortifications, also known as the Siegfried Line. It attacked on 13 December, with the support of the troops immediately to the south. By the evening of 15 December, the attack had broken a thousand-yard gap in the first line of fortifications, and the division’s 38th Infantry Regiment was moving forward to join the assault. The 23d Infantry, in divisional reserve, was south of the villages of Krinkelt and Rocherath (often referred to as the “twin villages”). Word of the 2d Division’s attack had not reached the Sixth Panzer Army headquarters when it launched its attacks on 16 December, so it did not know there were two divisions in front of it.13

The German attack, led by the LXVIII Corps on a sector screened by the 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, was understrength because one of the attacking divisions was not immediately available.14 Heavy automatic weapons fire from the cavalrymen swept the attackers and caused heavy losses. The cavalrymen held and were reinforced by an engineer combat battalion and later by the 9th Infantry Division.15

While the German attack fell all along the 99th Division’s front, this battle was about controlling the roads from the east and southeast to allow the panzers to advance through the 99th’s positions and drive into the American rear.16 The attacks posed a serious danger. The American supply line ran through Böllingen, Wirtzfeld, and the twin villages. The German front line was less than four miles east of the latter. German control of any of these villages would cut off much of the 2d Infantry Division and part of the 99th.17

The initial German attack was conducted by the 12th and 277th Volksgrenadier Divisions. The men in the divisions had been scraped together from wherever they could be found and given a few weeks of training.18 German after action reports commented on this problem.19 There were few combat-experienced company-grade officers and noncommissioned officers.20 The equipment and training of the panzer divisions also left much to be desired, and most were seriously understrength in their numbers of tanks, vehicles, and personnel.21

Despite its lack of training, the 12th Volksgrenadier Division was considered one of Germany’s best infantry units.21 Its commander, Major General Gerhard Engel, was Hitler’s former adjutant and saw to it that the division was brought up to a strength of 14,800 men and given a full complement of equipment, including the new Sturmgewehr 44 assault rifle.23

The first day’s attacks south of Höffen generally achieved some success. Directly east of Krinkelt and Rocherath, the German infantry of the 277th Volksgrenadier Division moved promptly as their artillery fire lifted. The 99th’s Company K, 3d Battalion, 393d Infantry Regiment (3-393d IN), was positioned at the south end of the battalion sector, guarding the junction of a trail and an east/west road. The Germans overran two platoons and forced the rest of the company to fall back. This exposed the battalion’s flank, forcing it to fall back west and consolidate around the battalion command post. The German corps commander ordered a battalion of SS panzer grenadiers to join the attack. The Germans could not dislodge 3-393 IN, but they penetrated far enough to put some Germans across that battalion’s only clear line of retreat.24

Further south, more Volksgrenadiers hit 1st Battalion, 393d Infantry Regiment (1-393 IN). American infantry, with their positions located at the edge of forested land, had clear fields of fire with artillery registered in front of them, and they threw back the Germans with heavy losses. Unfortunately, Company C on the right flank needed to be positioned well within the forest to cover a second road and a trail. When the attack was renewed, the Germans overwhelmed Company C’s positions one by one. Somewhat later, two of Company B’s platoons also had to retreat. A counterattack by the reserve company restored Company B’s positions. Following that, a bayonet charge by the reserve company, now augmented by the 1-393 IN’s Mine Platoon and a few men from the battalion headquarters, drove off an attack on Company C’s command post and formed a new line based on it.25

The next unit to the south, 2d Battalion, 394th Infantry Regiment (2-394 IN), repulsed a dawn attack by the 12th Volksgrenadier’s fusilier battalion and another at midmorning supported by assault guns. Artillery drove off the assault guns, but the fusiliers continued to attack. The Americans had overhead cover, and the attack was broken up when the American artillery fired airbursts on the frontline American positions.26

The main thrust of the 12th Volksgrenadier Division, aided by a parachute unit on its left flank, was made further south, where two paved roads and a trail led from Losheim into the 99th Division’s positions. A crucial part of the German plan was to open these roads so that a strong Kamfpgruppe of the 1st SS Panzer division under Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Joachim Peiper could move through and attempt to secure a crossing of the Meuse River.27

Most of 12th Volksgrenadier Division was committed to the attack. Its 48th Volksgrenadier Regiment attacked through the dense woods in the north part of its sector. The 27th Volksgrenadier Regiment attacked along the railroad line to the south and the parachutists attacked along the Losheim road. The attack was supported by all the divisional artillery, two Volksartillerie corps, and fifteen 75mm assault guns.28

This level of artillery support was unusual. German artillery did not come close to the uniformity of weapons, equipment, and sophistication of fire control of American artillery. Even if the German artillery had been better trained and equipped, it was not as useful as it might have been in this situation. The terrain made it difficult to identify targets, and the German batteries lacked the spotter planes the Americans found so useful. To add to this, the poorly trained Volksgrenadier divisions did not know how to make proper use of artillery support.29 Furthermore, the fire plan had not been well thought out.30

The German assault was opposed by 1st Battalion, 394th Infantry Regiment (1-394 IN), with 3d Battalion, 394th Infantry Regiment (3-394 IN), minus a company, nearby in divisional reserve, and the regimental I&R platoon in the area. The attack by the two battalions of the 48th Volksgrenadiers hit the seam between two companies. The Germans hit Company B in the flank and rolled up its line of foxholes. Company D fared better because communications problems caused heavy German artillery fire to fall on the attacking battalion. A group of Germans went around the end of Company B’s line heading toward the crossroads village at Losheimergraben. They discovered an 81mm mortar platoon was in their way when they were only fifteen yards from the tubes. The attack was broken up when the platoon began dropping mortar rounds on the attackers.31 Dropping rounds this close required both exceptional skill and courage.32

Company L, 3-394 IN, manned a blocking position near a deep railroad cut. The advance guard of the 27th Volksgrenadiers stumbled upon them and were taken under fire. Another company of 3-394 IN joined in the confused fighting that lasted until noon when the Germans retired. The Americans remained under heavy artillery fire for the rest of the day.33

The Luftwaffe 3d Parachute Division attacked further south to open a supply route for Kampgruppe Peiper. The mission of the Kampgruppe was to seize a crossing of the River Meuse.34 The Germans would have fed Luftwaffe ground troops into the fight and turned the 99th Infantry Division’s flank, except for the heroic fight put up by the 394th Infantry’s I&R Platoon at their outpost above Lazarath.35 Holding for almost twenty hours, the I&R Platoon was later awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for their heroic stand, the smallest unit to receive it. The fight showed that the 3d was no longer an elite division.36 As a result of the American resistance, Kampfgruppe Peiper finally broke clear of American defenses a day later than planned.37

The situation to the south was not good, but in the middle of the 99th Division’s sector, the Americans were in a truly precarious situation.38 Seven of the 99th Infantry Division’s infantry battalions, two of the division’s artillery battalions, all three battalions of the 395th Infantry, and armored vehicles from several units were north of the twin villages. The only way out was back through them.39 The Germans had hit the 393d Infantry east of the twin villages, and German forces were either behind the regiment’s battalions or the battalions had fallen back. There was a real danger that they would capture the twin villages and force the cut-off troops to surrender.

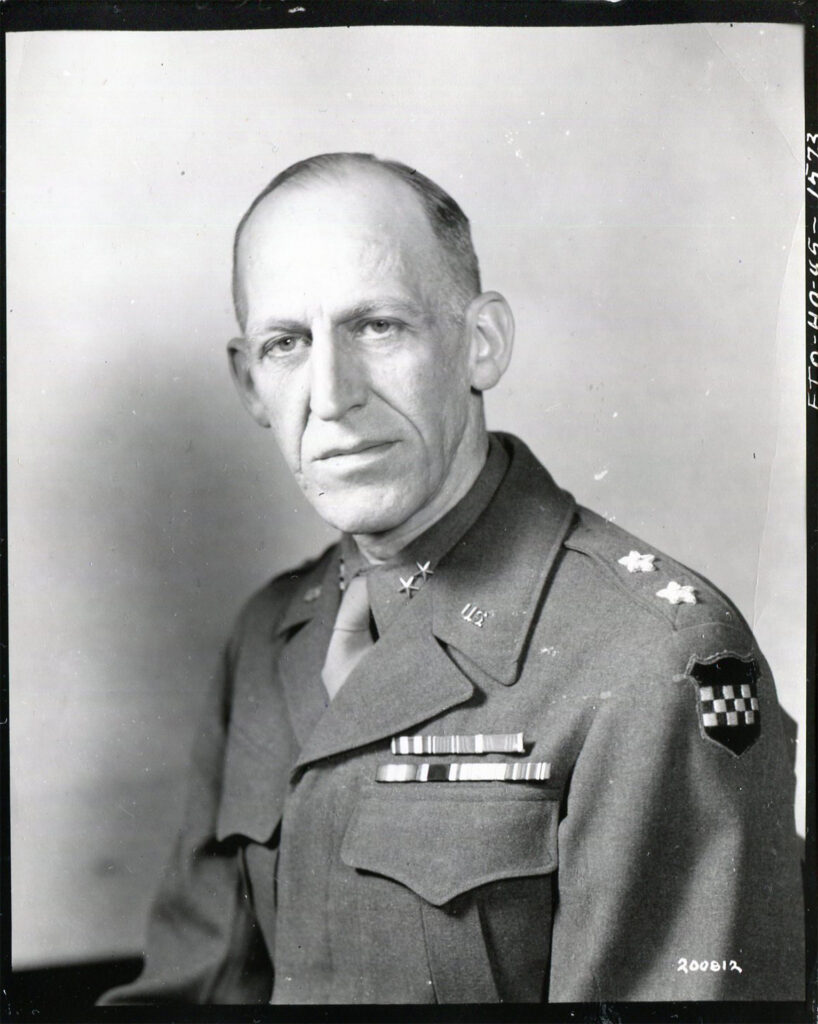

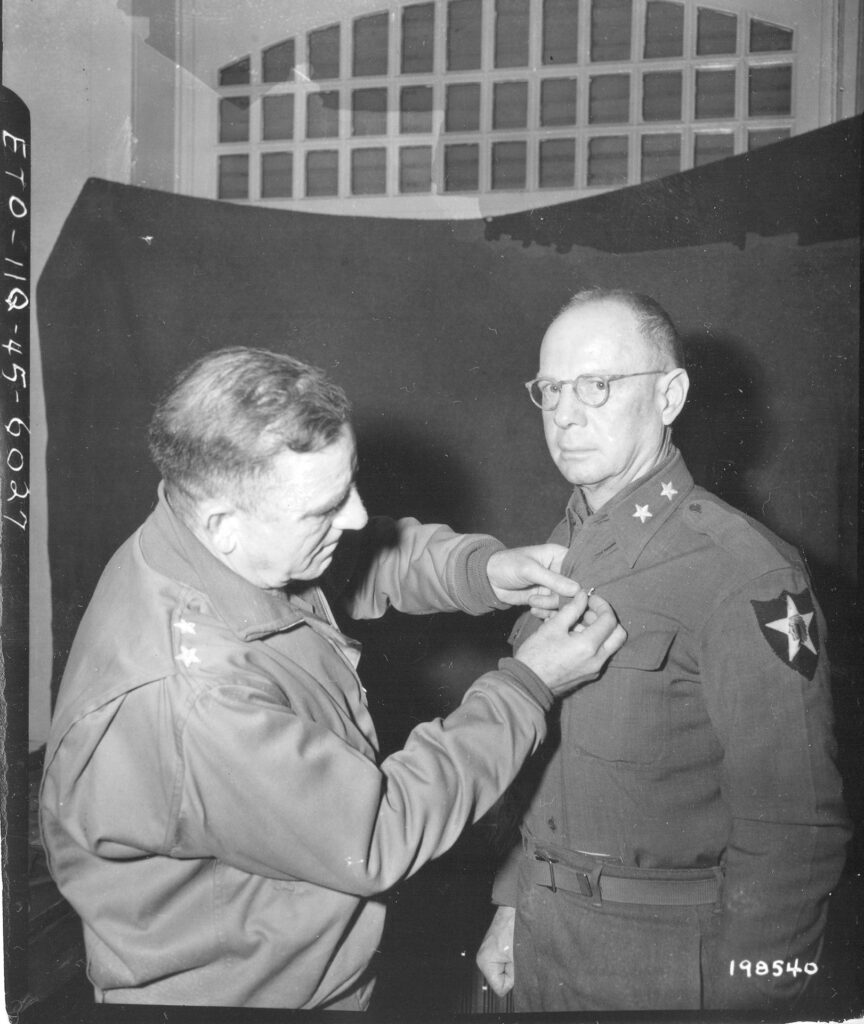

By mid-morning, Major General Walter M. Robertson, commander of the 2d Infantry Division, received information that there was confusion among the 99th Division’s leadership and that the division was in more trouble than realized.40 Early in the afternoon, Robertson asked V Corps commander, Major General Leonard T. Gerow, for permission to call off his attack. The request was denied by Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges, commander of First Army. Robertson moved his 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry Regiment (3-23 IN), north where it could defend the twin villages. About mid-afternoon, he received orders to detach the regiment’s other two battalions to the 99th Division. 3-23 IN was to shore up the south end of the 99th’s line by occupying prepared positions behind the 394th Infantry near Losheimergraben.40 2d Battalion, 23d Infantry Regiment (2-23 IN), was to move into the forests east of the twin villages and attack at dawn to restore the positions of 3-393 IN.41

On his own initiative, Robertson stopped the attack by the 9th and 38th Infantry but left open the possibility of a resumption of the attack the next morning. He went forward and confirmed that his regimental commanders understood the seriousness of the situation, and that they had alerted their battalion commanders to begin planning for withdrawal. He returned to his headquarters and began making his own plans.42

Major Walter E. General Lauer, commander of the 99th Infantry Division, did not seem to have grasped the seriousness of the situation. Late that night he reported to Major General Gerow that all of his units occupied practically the same positions they had held at dawn. While his troops had done well, 3-394 IN was semi-isolated and many of his battalions had taken heavy losses. His 394th Infantry had captured a message from Field Marshal Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt, the German commander-in-chief in the West, exhorting his troops that “the hour of destiny had struck,” so it should have been clear that this was a major push.43

The attack was about to be renewed with considerably more force. Opposite the twin villages, the 12th SS Panzer Division, aided by the depleted 277th Volksgrenadier Division, was committing substantially more infantry and a significant number of tanks. Further south, the 12th Volksgrenadier Division was massing its assault guns and infantry for another attack.44

At 0700 on 17 December, Robertson received orders to break off his attack and for the 2d and 99th Divisions to withdraw about four miles west to the dominant high ground, an area the Americans called Elsenborn Ridge. To accomplish the withdrawal, the Americans needed to keep control of the road from the Wahlersheid station, through the twin villages, and at least as far as Wirtzfeld.45 There, engineers had been working to improve a back road to the ridge. About the same time, Robertson learned that German armor was in Büllingen to the south.46 The crumbling front added to the difficulty of the move. Robertson had lost communications with the 99th’s headquarters, so he had no idea how well the 99th’s battalions were holding against the Germans.

Robertson was about to execute one of the most difficult military maneuvers: a daylight withdrawal while in contact with an aggressive enemy. The immediate task was to shore up the positions at the twin villages while pulling the artillery back to where it could support the withdrawal. The reserve battalion of the 38th Infantry was to move first to defend the southern periphery of Krinkelt, followed by the artillery battalions. Once these supporting units were in place, Robertson planned what he called “a skin the cat” maneuver. The forward battalions would move south toward the twin villages.47 This put the depleted 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment (1-9 IN), at the rear of the regiment. The forward battalions of the 38th Infantry would shield the 9th until it passed. Then they would move south along the road. Tanks and self-propelled tank destroyers would be scattered along the column.48

Again, on his own initiative, Robertson attached the three battalions of the 395th Infantry, which were holding the northern part of the 99th divisional front, to the 2d Division. These units would pull out after the more forward-deployed 2d Division elements and move into defensive positions north and east of Rocherath.49

On the morning of 17 December, the 48th Volksgrenadier Regiment, 12th Volksgrenadier Division, backed by panzers renewed its attack on Buchholtz Station and Losheimergraben. Half of the defenders had been pulled out the day before to man positions behind Losheimergraben. As in the day before, there was trouble coordinating German artillery fire, but once that was rectified and a second regiment joined the battle, the village quickly fell. This imperiled the positions of the rest of the 394th Infantry. The commander ordered its withdrawal to prepared positions around Hünningen and Murringen where 1st Battalion, 23d Infantry Regiment (1-23 IN), was already positioned.50

The inexperienced staff of the 99th Division seemed to be “in a state of shock” and had little knowledge of the location of American and German forces.51 In the early afternoon of 18 December, Gerow met with Robertson and Lauer to work out a plan for withdrawal to Elsenborn Ridge. Gerow made Robertson his deputy and temporarily attached the 99th Division to the 2d.52

On the night of 16 December, 3-23 IN deployed to a road junction deep in the forest east of Krinkelt and prepared to support the attack of 3-393 IN. The commander of that battalion thought he could counterattack and recover his lost positions without help, so early in the morning of 17 December, 3-23 IN’s mission was changed to occupy a backup defensive position. The battalion was spread throughout a half-mile of dense forest instead of being concentrated to defend the two roads through their position. The battalion was short of ammunition and its only antitank weapons were a few bazookas and a handful of rockets.53

On 16 December, 2d Battalion, 23d Infantry Regiment (2-23 IN), had one company at the southern edge of Krinkelt with the rest of the battalion defending the area between Krinkelt and Büllingen. On 17 December, the battalion moved to Büllingen to shield that village from what was thought to be a threat from Kampfgruppe Peiper.54

As 3-393 IN was launching its attack, the 12th SS Panzer Division fed a battalion of panzer grenadiers and four companies of tanks into the battle. This forced the Americans onto the defensive. Ammunition was running low and casualties were piling up. By mid-morning, 3-393 IN received orders to pull back through 3-23 IN. By 1100, they were moving back along the road.55

Hardly had they passed through 3-23 IN when that battalion saw panzer grenadiers forming up to attack. 3-23 IN held against two attacks, but a third, accompanied by panzers, forced the battalion into a confused retreat.56

Robertson spent most of 17 December moving up and down the Wahlerscheid road coordinating the retreat. At about 1600, Robertson learned about 3-23 IN being overrun and that the two Shermans backstopping it had been knocked out. The Germans were now free to move into the twin villages.57

The first unit Robertson could contact to oppose the Germans was Company K, 9th Infantry, just north of Rocherath. He hastily moved them into position near a farmhouse halfway between the village and the forest to the east and reinforced them with a platoon of heavy machine guns and a regimental pioneer platoon. The position was along an open pasture with good fields of fire, but nothing to tie into on the flanks.58 Looking further, he found 1-9 IN that had led the fight at the Wahlerscheid crossroads in bitter cold. Although exhausted by the ordeal, he brought them to where Company K was digging in and ordered them to hold the position “until ordered otherwise.” Fortunately, the soldiers occupying the position acquired a supply of antitank mines, fifteen bazookas, and plenty of rockets.59

At about 1730, groups of panzer grenadiers and accompanying tanks began to reach the American position. The GIs halted most of the enemy troops, but in the confused darkness, some passed through gaps in the line of foxholes or around the flanks of company positions without being engaged, and advanced into the villages. Other groups took heavy casualties from artillery, but still, the survivors continued toward the twin villages.60

An hour after the first Germans appeared in front of 1-9 IN’s position, the Germans put in a concerted push with tanks and infantry along all three trails that ran through the American defenses. First Lieutenant John C. Granville, the battalion’s artillery liaison officer, called for artillery. The barrage that came was so heavy that it seemed nothing could survive it. Robertson considered the position so vital that he gave Granville priority of fires from four battalions of divisional artillery and three battalions of corps 155mm howitzers. The Germans attacked with great determination, but around midnight, the survivors retreated. The defenders had effectively employed rifles, machine guns, bazookas, antitank guns, and mines, but it was the artillery that stopped the German advance.61

The twin villages were unlike most European farming villages, with several parallel streets. The houses were separated by yards surrounded by trees and bushes, ideal spots for a Sherman or an M10 tank destroyer to lie in wait. Brave men with bazookas could use the cover to avoid the heavy frontal armor of the Mk. IVs and Panthers and get shots at vulnerable tank tracks and drive wheels.62

Robertson deployed his only reserve battalion, 3d Battalion, 38th Infantry Regiment (3-38 IN), on the east and south sides of the twin villages. As this was happening, 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry Regiment (1-38 IN), and 2d Battalion, 38th Infantry Regiment (2-38 IN), moved down the road from Wahlerscheid, taking casualties, sometimes heavy, from German artillery.63 When they reached the twin villages, Robertson used them to extend the perimeter along the north side of the villages and around to the west. The 99th’s support units had pulled out, but stragglers from the 99th Division and 3-23 IN were coming in to attach themselves to units there or take up positions in the houses.

There was incredible confusion in and around the villages.64 The artillery of both sides pummeled the area, and flares burned overhead. German tanks and houses in the villages burned and German machine guns fired from the distant edge of the forest. The place was a fiery cauldron. Attacks and ambushes within the villages added to the noise and there was no front line.65 Through this inferno, groups of filthy and exhausted soldiers stumbled about in the confused fighting.66

In 1-38 IN’s position, Company A found foxholes already dug, but Companies B and C had not had time to dig in when they were hit by three panzers and a party of panzer grenadiers. Those companies disintegrated. Their attackers continued into the village, where they were met by fire from scattered troops from several units and from 1-38 IN’s headquarters.66 Fortunately, 2-38 IN successfully defeated German attempts to penetrate its position.67

Other parties of panzers and panzer grenadiers slipped into the villages. One party of three panzers and forty panzer grenadiers led by Obersturmbannführer Helmüt Zeiner bounced off the defenses, then slid-slipped and moved into the villages, shooting up positions. Other parties blocked the road to Wirtzfeld.68 Together, with the German artillery falling on the villages, they created the impression of a much larger force. However, realizing they were greatly outnumbered, Zeiner’s party went to ground and quietly left the villages in the early hours of 18 December, herding eighty prisoners with them.69 About midnight, the head of a column of 99th Division vehicles reached Krinkelt and continued through the town for the rest of the night.70

By morning, there were substantial numbers of American infantry, tanks, and tank destroyers in the town and a formidable force of artillery to the west. As they defeated the groups of Germans in the villages, the defenders began to believe they could hold off the attacks from the east.71

On 17 December, the situation in the southeast, was, if anything, more confusing. The plan was for the 1-23 IN to occupy positions at Hünningen and the rest of 38th Infantry’s battalions to tie in to the east. Colonel Don Riley, commander of the 394th Infantry, was unsure of the location of his battalions and that of the attached 1-23 IN. That battalion threw back seven attacks but was badly exposed and only holding on because of the supporting fires of two artillery battalions. When Lieutenant Colonel John M. Hightower of 1-23 IN asked permission to withdraw, Riley refused, not knowing how that would affect his battalions. At about 2200, Hightower was notified that he was now attached to the 9th Infantry in Wirtzfeld, and he was ordered to withdraw to avoid being cut off. Riley queried his division command, and the change in attachment was confirmed; Hightower was authorized to withdraw his battalion.72

The withdrawal of the four battalions began around 0200 on 18 December. Confusion still reigned. 1-394 IN had been splintered into isolated groups, and they were unaware that the regiment had evacuated Mürringen behind them. When two companies approached, the Germans opened up with murderous fire. Only artillery firing on the village enabled the Americans to withdraw.73 Other columns were taken to be Germans and found themselves under friendly fire. The sound of combat from the twin villages encouraged the various groups to head for Wirtzfeld, but before this could happen, it was discovered that Krinkelt was partly under American control so that route to the rear was open.74

The morning of 18 December found 1-9 IN and Company K still defending the twin villages from an attack from the east while two battalions of the 38th Infantry successfully took up positions behind them and began to dig in.78 When the Americans pulled out of the twin villages, they encountered a formidable force of eight tanks, several 88mm cannon-equipped tank destroyers, and two battalions of panzer grenadiers preparing to assault 1-9 IN. The German assault began around 0700 on 18 December.

The Americans held determinedly, with no panic, while artillery wreaked havoc on the enemy armor and panzer grenadiers. The Germans, for their part, clambered over their dead to try to reach the American lines. Both sides displayed incredible courage. First Lieutenant Stephen E. Tuppner, commander of Company K, 9th Infantry, ordered artillery to fire directly on his company’s position as it was being overrun. He was never heard from again. The remnants of Company K, a handful of men, were forced to surrender when a panzer aimed its main gun at them from a few feet away.75

By 18 December, much of the 99th Infantry Division’s line of platoon-sized positions became “isolated islands of resistance” that were surrounded or trying to break contact and retreat.76 What was left of 1-9 IN was authorized to withdraw at noon. The Germans, however, were engaging them so closely that most of the men were sure to become casualties as they left their foxholes. Miraculously, the leader of the battalion antitank platoon saw a platoon of four Shermans patrolling nearby. When asked if they wanted a fight, their platoon leader responded, “Hell yes!” There were four German tanks hidden in positions and prepared to fire on the withdrawing Americans. Two of the Shermans took concealed positions while the other two lured the Germans out of their cover. The American tanks knocked out three of the panzers and forced the fourth to flee. The Shermans then positioned themselves to fire on the Germans trying to pursue the withdrawing infantrymen.77

Two-thirds of 1-9 IN and its attachments became casualties, but their heroic defense allowed the two battalions of the 38th to reach the twin villages and dig in. Were it not for the sacrifices of 1-9 IN, much of the 99th Division and most of the 2d would have been lost. In a battle where so many displayed such valor, no one exceeded their bravery.78

While the fighting around the position of 1-9 IN took place, other German units mounted a dawn tank/infantry assault that overran parts of the twin villages. Confused fighting there continued all day and into the night.79

By noon on 17 December, the situation at Wirtzfeld had stabilized.80 The 26th Infantry of the 1st Infantry Division, was moving in around Butgenbach on the south end of the Elsenborn Ridge to shore up that flank and interdict the supply route for Kampgruppe Peiper.81 That night, Major General Robertson learned, to his relief, that the rest of the 1st Division was moving to extend the line further west ending the danger of being outflanked.82

About midnight on 17 December, Robertson and Lauer agreed that Lauer’s troops and anyone available would concentrate on organizing positions for both divisions on Elsenborn Ridge while the 2d Division held the twin villages.83 By 18 December, the Americans had also assembled a coherent defense of the twin villages supported by a tank battalion, a tank destroyer battalion, and parts of two other tank destroyer battalions. 99th Division troops and vehicles continued to stream through.

Late in the afternoon of 18 December the commander of the 395th Infantry that Robertson attached to the 2d Division on his own initiative received a coded message to withdraw to Elsenborn. To the 395th’s commander, Colonel Alexander J. Mackenzie, that seemed odd, because he had heard nothing that ended his attachment to the 2d Division. He initiated the move but went ahead to Major General Lauer’s headquarters at Elsenborn, where he found that the order was a mistake or bogus. The weary troop turned around to reoccupy their positions.84

On 18 December, 3-395 IN at Höffen was hit by an assault of tanks and supporting infantry. German troops and armor broke into the Americans’ positions, but they were eventually driven back. German losses were 554 dead and fifty-four captured. American losses were five killed and seven wounded.85 As the 9th Infantry Division moved into line around Höffen, 3-395 IN withdrew along a single muddy trail to Elsenborn.86

By 19 December, the Germans had realized that the three designated routes for their planned advance that went through the north shoulder were not going to fall into their hands.87 Insistence that the attacking troops not deviate from their assigned tasks meant that the Germans forfeited the chance on 16 December for Kampgruppe Peiper to roll up the American flank.

their last rounds and were forced to surrender. McGarity was awarded the Medal of Honor on 11 January 1946

by President Harry S. Truman. (National Archives)

Early in the afternoon of 19 December, the Americans began destroying any vehicles and material in the twin villages that could not be removed. Vehicles not essential for the defense moved up to Elsenborn Ridge in ones and twos. After dark, beginning with the battalions furthest north, the defenders of the twin villages began peeling off towards Wirtzfeld and to designated positions on the ridge.88

Before dawn, the 12th SS Panzer Division began notifying vehicle crews that could be contacted to retire with any vehicles that they could still operate from the area around the twin villages. What was left of the panzer units began to withdraw from contact. The Americans had won this phase of the Battle of the Bulge.

Volksgrenadier units moved in behind the withdrawing panzers to keep pressure on the defenders. They made several small attacks on American positions to cover the withdrawal, which were easily repulsed. Once the battle was over, it was clear that two American infantry divisions, with considerable help from supporting units, had held off the attack of a much larger force until reinforcements arrived.

After the retreat to Elsenborn Ridge was complete and other divisions moved in on the flanks of the position, the story of the north shoulder merges with the broader story of the Battle of the Bulge. On the southern margin of the shoulder, the priority now became controlling the high ground around Bütgenbach. The planned German supply line to Kampgruppe Peiper was to run just to the south of the village. The 1st Infantry Division posted a battalion of its organic 105mm howitzers and a battalion of attached 90mm antiaircraft guns, which could engage ground targets, to interdict that supply line.89 Cut off from supplies and taking heavy casualties, Kampgruppe Peiper eventually ran out of fuel; what remained of its personnel trudged back to German lines.

There were many things that the Germans did, or failed to do, that contributed to their defeat on the north shoulder. Hitler’s insistence that the troops only attack when and where he designated and along the routes his staff designated, cost them the chance to roll up the right flank of the American position. He directed the attack through terrain where it would be difficult for better-trained troops than the Germans had available to avoid uncoordinated, piecemeal attacks. They did not mount a heavy-weighted blow at the twin villages until after the Americans had positioned strong forces there.90 Furthermore, they greatly underestimated the Americans’ ability to move troops and supplies to threatened sectors, and the mental flexibility that allowed them to make prompt use of that mobility.

The German failure to break through the north shoulder cost them the battle. Their inability to use the five planned routes created delays and clogged roads that gave the Army Air Forces and the Royal Air Force plentiful targets once the weather cleared. It is a myth that Germany was counting on capturing American gasoline. The Germans had almost five million gallons of fuel stockpiled for the attack, but they simply could not get it to where it was needed.91

The 99th Infantry Division’s performance was remarkable for a division new to battle and so disadvantageously positioned to meet the German attack. The division’s GIs fought an enemy that badly outnumbered them and, in the early stages of the battle, had far more armor and artillery support. Despite the disparity in numbers, the untested infantrymen of the 99th held the attackers while other troops prepared the defense that ultimately stopped them.

There were many reasons for the American success in the north shoulder of the Bulge. The “dreadful wrath” of the splendid American artillery played a decisive role in so many of the engagements of the 2d and 99th Infantry Divisions.92 In addition, effective cooperation between the combat arms made each of them far more effective than if they had been employed separately.93

Much credit must go to the American soldier whose competence and tactical skill were greatly underestimated by the Germans. Confusion on the battlefield has been referred to several times to point out the importance of the determination and individual initiative of the men in the ranks.

Credit must be given where it is due—the north shoulder remains a triumph for the 2d Infantry Division. V Corps commander Major General Gerow attached the 99th Division to the 2d for the move to Elsenborn Ridge because he was impressed by the 2d’s determined defense and intelligent employment under Robertson’s leadership. Robertson’s actions from the beginning of the fight showed that Gerow’s judgment was correct. Throughout the battle, Robertson’s actions showed that he was one of the best American combat commanders in the European Theater.95

One of the most interesting commentators on the battle was then-company commander Charles B. MacDonald, who led Company I, 3-23 IN, when it was overrun on 17 December. According to MacDonald,

Between December 13 and 19, the 2nd Division had penetrated a heavily fortified section of the West Wall, then executed an eight-mile daylight withdrawal while in close contact with the enemy and assumed defensive positions at the twin villages facing another direction. There they came immediately under heavy attack, held the villages for two days and nights while the troops of the 99th Division streamed through, and then broke contact and withdrew to new positions on Elsenborn Ridge.96

The success of the 2d Division required heroism and sacrifice at all levels. Robertson’s book, Combat History of the Second Infantry Division in World War II, is, in considerable part, made up of extracts from citations of decorations written by 2d Division personnel, which were awarded to men who played key parts in the division’s success. Given the constant confusion on the battlefield, we can be sure that many more men equally deserved recognition. Lieutenant General Hodges, commander of First Army, summed it up well in his commendation of the 2d Division: “What the 2nd Infantry Division has done in the last four days will live forever in the history of the United States Army.”97

Endnotes

1 Charles B. MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge (New York: Bantam Books, 1985), 161.

2 Antony Beever, Ardennes 1944 (New York: Penguin Random House, 2015), 91.

3 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 30.

4 Ibid,162.

5 ibid,161.

6 Hugh M. Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge (Atlanta: Whitman Publishing, 2012), 121.

7 Hans Wijers, The Battle of the Bulge: The Losheim Gap/Holding the Line, Volume 1 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2009), 38.

8 Ibid, 210.

9 Cole, The Ardennes, 79

10 Ibid, 78.

11 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 166.

12 Trevor N. Dupuy, Hitler’s Last Gamble: The Battle of the Bulge, December 1944-January 1945 (New York, Harper Perennial, 1995), 29-31.

13 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 162.

14 Ibid, 165.

15 Ibid, 166.

16 Cole, The Ardennes, 78.

17 Ibid (Map), 11.

18 Interview of Thuisko von Metzsch in Danny S. Parker, Hitler’s Final Push: The Battle of the Bulge from the German Point of View (New York: Skyhorse Publishing Company,2016), 204; Keith E. Bonn, When the Odds Were Even: The Vosges Mountains Campaign, 1944-1945 (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1994), 46.

19 Cole, The Ardennes, 128.

20 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 168.

21 Wijers, The Battle of the Bulge, 218, 220.

21 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 167.

22 Ibid, 168-9,

23 Stephen Rusiecki, The Key to the Bulge: The Battle for Losheimgraben (Mechanicsburg, PA” Stackpole Books, 2009), 18.

23 Ibid, 170.

24 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 168.

25 Ibid, 168-9.

26 Ibid, 170.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid, 171.

29 Beevor, Ardennes 1944, 121.

30 Rusiecki, The Key To The Bulge, 28.

31 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 172.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid, 173-4.

34 Ibid, 166.

35 Ibid, 175-9.

36 Alex Kershaw, The Longest Winter: The Battle of the Bulge and the Epic Story of World War II’s Most Decorated Platoon (New York: MJF Books, 2004), 120.

37 Rusiecki, The Key to the Bulge, 21.

38 MacDonald, A Time for trumpets, 179.

39 Cole, The Ardennes, 95.

40 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 179.

41 Ibid, 180; Walter M. Robertson, Combat History of the Second

Infantry Division in World War II (Baton Rouge: Army and Navy Press, 1946), 87.

42 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 181.

43 Ibid, 181.

44 Ibid, 182.

45 Ibid, 181,372.

46 Cole, The Ardennes, 104.

47 Ibid, 372.

48 Ibid, 373-74.

49 Ibid, 373.

50 Ibid, 374.

51 Ibid, 389.

52 Ibid, 120.

53 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 375-76, Cole, The Ardennes, 99

54 Cole, The Ardennes, 105.

55 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 376-7.

56 Ibid, 376-80.

57 Ibid, 380.

58 Ibid.

59 Cole, The Ardennes, 109.

60 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 382.

61 Ibid, 183.

62 Ibid.

63 Ibid, 384.

64 Wijers, The Battle of the Bulge, 190.

65 Ibid, 399.

66 Ibid, 386.

67 Ibid, 399.

68 Robertson, Combat History of the Second Infantry Division, 98.

69 Ibid.

70 Cole, The Ardennes, 111.

71 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 401; Cole, The Ardennes, 124.

72 Robertson, Combat History of the Second Infantry Division, 93; MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 388.

73 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 392.

74 Cole, The Ardennes, 105.

75 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 395.

76 Robertson, Combat History of the Second Infantry Division, 93; McDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 391.

77 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 397.

78 Ibid, 395-99.

79 Ibid, 398.

80 Robertson, Combat History of the Second Infantry Division, 95.

81 Cole, The Ardennes, 113.

82 Robertson, Combat History of the Second Infantry Division, 90.

83 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 394.

84 Ibid, 392.

85 Ibid, 395.

86, Cole, The Ardennes, 122.

87, MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 401.

88 Ibid, 402.

89 Cole, The Ardennes, 113.

90 Wijers, The Battle of the Bulge, 127.

91 Ibid,68.

92 William G. Dennis, “A Comparison of American and German Artillery in World War II,” On Point: The Journal of Army History (Winter 2017): 10; MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets,395, 405, 409; Robertson, Combat History of the Second Infantry Division, 96.

93 Cole, The Ardennes, 124.

94 MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, 401.

95 Ibid, 409.

96 Ibid, 410.

97 Ibid.

About the Author

William G. Dennis earned a B.A in History/Political Science from Whitman College before enlisting in the Army and attending Infantry Officer Candidate School. As an Amy officer, he served as a 4.2-inch mortar platoon leader and as a headquarters/ weapons company commander. He later earned a B.S. in Geology and a Juris Doctor. In addition to articles for On Point, he has been published in several other history magazines as well as Washington State Bar News.