By Joshua Cline

“The Army has had two great trainers,” General Dwight D. Eisenhower once asserted. “Von Steuben, and Bruce Clarke.” A relatively obscure figure in the pantheon of notable American military leaders, Bruce C. Clarke holds a position of quiet importance in Army history. He is one of the few four-star generals to have entered the Army as a private. A soldier with an almost unparalleled record of victories in World War II, Clarke played an important role in early Cold War U.S. Army and NATO commands. He spearheaded the effort to integrate the Army after segregation was abolished. He paid special attention to noncommission officers (NCOs) and encouraged lessons that endure to the present. Clarke pioneered innovation in armor tactics and intense, realistic training within the Army, especially within his twin loves of the Armored Force and the Corps of Engineers. Of note was Clarke’s rebuilding efforts and public relations focus, which garnered much goodwill with key allies, even after his retirement.

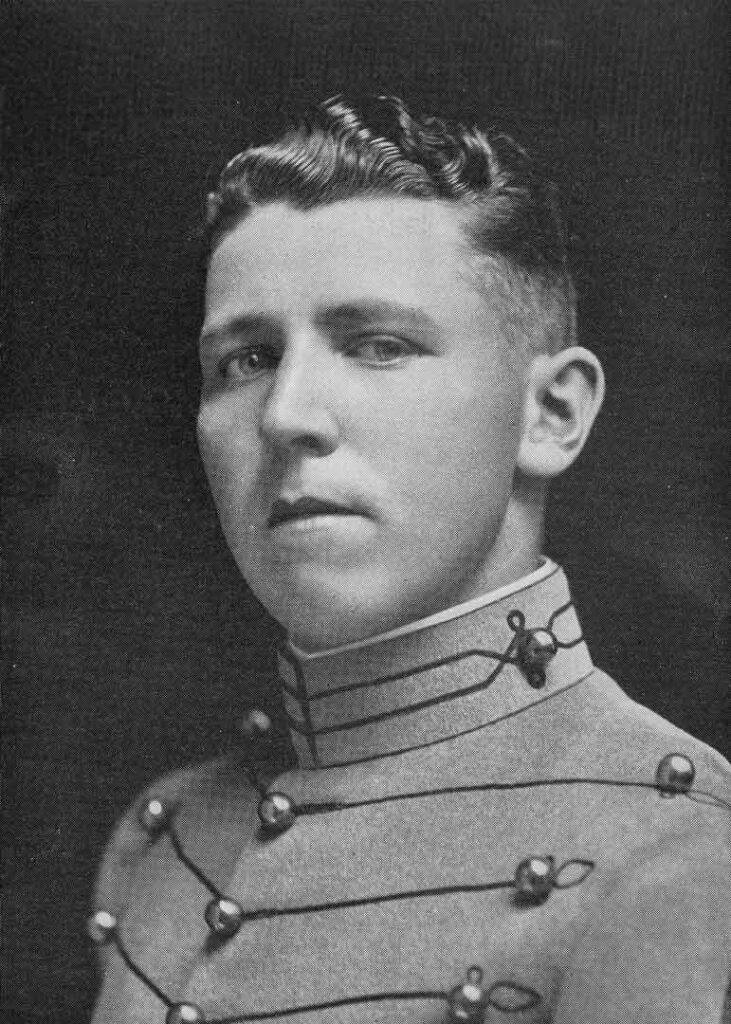

Bruce Cooper Clarke was born on 29 April 1901 in Adams, New York. He dropped out of high school and enlisted in the Army at the age of sixteen on 5 April 1918 in Watertown, New York, using his considerable height (slightly over six feet) to lie about his age. He was assigned to the Coast Artillery Corps, but World War I ended while he was still in training and he was discharged later that year. Clarke then joined the New York National Guard on 5 January 1920. Assigned to the 106th Field Artillery, Clarke rose to the rank of corporal before being accepted as a cadet at the U.S. Military Academy, with barely two-and-a-half years of high school to his name. Cadet Clarke entered West Point on 1 July 1921 with the Class of 1925. He graduated thirty-third in a class of 248 on 12 June 1925, earning his first choice of branch, the Corps of Engineers, and a commission as a second lieutenant. Later that same day, he married Bessie Mitchell.1

Second Lieutenant Clarke’s first assignment was with the 29th Engineer Topographic Battalion at Camp Humphreys, Virginia. He was selected to attend Cornell University for a degree in civil engineering, which he completed by mid-1927. This was followed by attendance at the Engineer School at Camp Humphreys in 1928, while simultaneously commanding the Engineer School’s Colored Detachment, gaining early experience in commanding black soldiers.2

Clarke returned to the 29th briefly before being sent to the 3d Engineer Regiment at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, mixing the duties of platoon leader and regimental supply officer from 1929 to 1932. One of Clarke’s observations from this duty was “A unit is measured by the ability of the lower third personnel in it to carry their part of the load…If you want to create an outstanding Army unit, you must motivate the lower third of your men.” Clarke was promoted to first lieutenant on 1 September 1930.3

In 1932 Clarke became an instructor of the ROTC detachment at the University of Tennessee. On 1 August 1935, he was promoted to captain. In 1936, Clarke was posted to the Galveston Engineer District as chief of the Engineering Division. According to Clarke, “I created a new organization of 50 professionals…we submitted over 40 reports to Congress.”4

Captain Clarke was assigned to the Command and General Staff College in 1939. This was the last class before World War II closed its doors, and the curriculum was cut down to five months. “I got an F on my last problem at Leavenworth,” Clarke recalled. “In the critique the man said ‘Fortunately Clarke is an Engineer. He’ll never have a chance to command tanks, so we don’t have anything to worry about.’” Clarke employed the same tactics in this last exercise at Fort Leavenworth with great success in Europe in 1944, and of it, he had to remark, “Patton gave me an ‘A’.”5

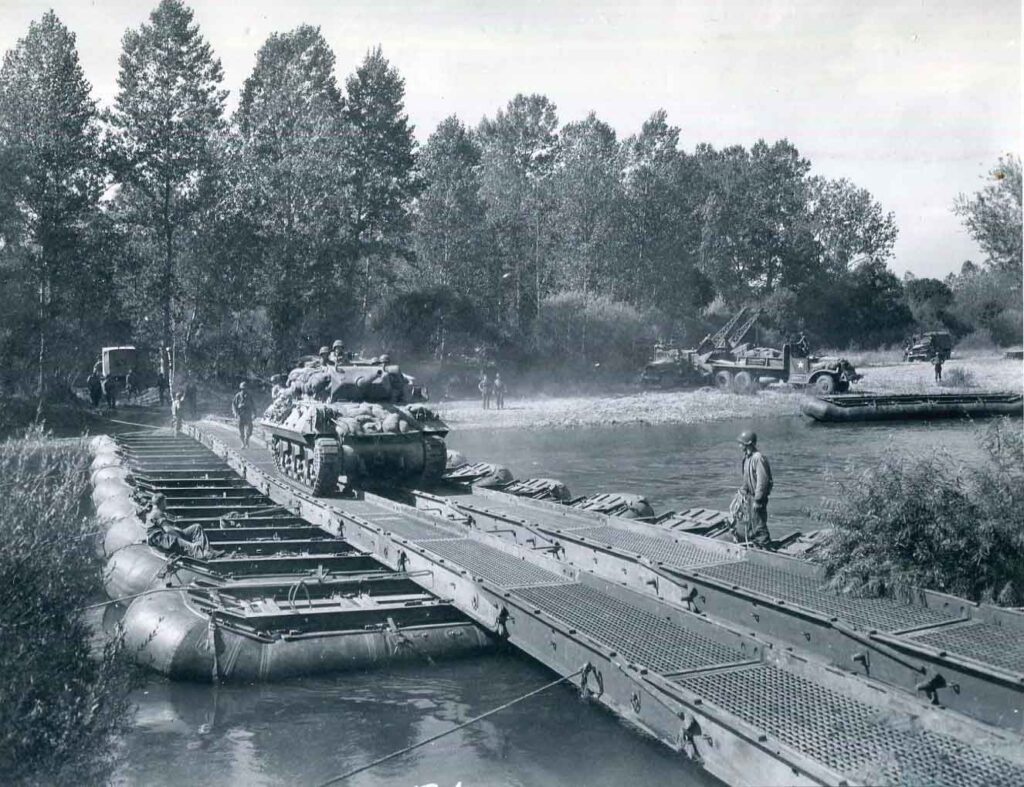

In April 1940, Clarke was assigned to Brigadier General Adna R. Chaffee, Jr.’s 7th Mechanized Brigade, commanding the 47th Engineer Troop (Mechanized), and serving as Chaffee’s brigade engineer. Clarke’s unit split to create the 16th and 17th Armored Engineer Battalions for the 1st and 2d Armored Divisions on 1 July 1940. Captain Clarke was acting Armored Force engineer, commanding officer of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, and 1st Armored Division engineer, all roles that higher-ranking officers would soon take. He was also appointed to the board that created the first Table of Organization and Equipment for an American armored division. Clarke’s next position was as an official observer to the British 1st Armoured Division in December 1940.6

Clarke was promoted to major on 31 January 1941. He organized and commanded the 24th Armored Engineer Battalion, 4th Armored Division, and again served as division engineer. Major Clarke’s battalion was selected as the division’s outstanding battalion on 24 December 1941, and he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. Three weeks later, he was made division chief of staff. Two weeks later, on 1 February 1942, Clarke was promoted again, this time to colonel. Clarke served as Chief of Staff, 4th Armored Division, from January 1942 to October 1943; for his work training the unit, Clarke was awarded the Legion of Merit.7

On 1 November, 1943, Colonel Clarke assumed command of the 4th Armored Division’s Combat Command A (CCA). When Lieutenant General George S. Patton’s Third Army was unleashed in France in July 1944, the 4th Armored Division served as its spearhead. Clarke commanded CCA until 31 October 1944, driving it through hundreds of miles of Nazi-held territory. “The uncanny thing about Clarke was the continuous success without a setback. When he’d say, ‘Today we’ll go here,’” said Colonel James Leach, “we would get there…The feeling you had was, if you’re with Clarke, you could win.” Clarke recounted one of his encounters with Patton: “I said, ‘General, by God, I run out of orders at 10:30 in the morning. I just can’t get an order from the corps that will last all day. What the hell do I do?’ He said, ‘Go east.’ I went 500 miles on two words.”8

While his executive officer manned the command post and directed the rear echelon elements, Clarke circled the head of his frontline columns in an L-4 Grasshopper reconnaissance plane, rode near the head of them in a jeep, or traveled in a uniquely modified M5 Stuart light tank with a dummy wooden gun which “could really move.” The L-4 was not an authorized part of Clarke’s command; according to Clarke, “We stole it from the artillery.” Clarke would later be awarded an Air Medal for the number of flights he conducted in his L-4.9

Clarke’s charge across France saw him repeatedly fighting surrounded, yet never too concerned. “The safest place to be in combat is…the enemy backfield…they’re going to solve that problem for you by getting the hell out of there.” Clarke believed that the only mistake possible when pursuing an enemy was to stop. His masterful attack upon the city of Troyes, for which he received the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), proved that tanks could be used effectively in urban combat. Patton himself interviewed Clarke to get the details, and “following Troyes, no commander of the division ever attacked a city without tank strength.” When Patton awarded him the DSC, Patton could not find the medal he was supposed to award, so he simply gave Clarke his own DSC.10

When Clarke had his Stuart or a jeep, he and his driver would advance to the head of a column, working through the convoy. Clarke carried a bucket of apples on his lap, and any unaware tank commander was liable to have an apple hit the back of his head. Lieutenant Colonel Creighton Abrams, commander of the 37th Tank Battalion, told his company commanders, “Clarke has no business that far forward, but for God’s sake let him by.”11

On 14 September, Clarke’s CCA was ordered to seize the high ground around Arracourt. The Battle of Nancy and the following Battle of Arracourt combined are what Clarke called his “greatest victory.” Clarke’s tactics at Arracourt are a classic example of a mobile defense for a surrounded unit, and showcased the advantages of having highly trained and experienced troops, better tactics, and close coordination with air support. Patton visited and spoke to Colonel Clarke on 15 September. The general abruptly commented, “Clarke, you are nothing but a God damned nobody.” Patton had been visited by General George C. Marshall, the Army’s Chief of Staff, for dinner. When Patton asked, “Why don’t you promote Clarke?” Marshall responded, “Never heard of him.”12

In a twenty-eight day period, Clarke participated in and led actions that would see him awarded three Silver Stars and a DSC; by the end of fifty-four days, he received the Air Medal and two Bronze Stars. General Jacob Devers, commander of 6th Army Group, said, “Bruce, Patton lived on what you and your combat command did.”13

Clarke was transferred to a unit that had suffered top-down leadership trouble, CCB of the 7th Armored Division, on 1 November 1944. His new superior, Brigadier General Robert Hasbrouck, ordered Clarke “to retrain this division. I want it trained like the 4th Armored. You’re going to be the trainer.” Clarke knew the way to fight the war in tanks and instilled those methods in a unit that had lost faith in previous commanders. On 7 December 1944, Hasbrouck pinned the star of a brigadier general on Clarke. Nine days later the Battle of the Bulge began.14

On 16 December, the town of St. Vith was defended by the ill-fated 106th Infantry Division. The entire German counteroffensive relied on supply routing through St. Vith for two whole panzer armies. Consequently, those two armies attacked Major General Alan Jones’s undermanned and inexperienced division. Two of Jones’s units, the 422d and 423d Infantry Regiments, became surrounded as the result of miscommunication. Major General Troy Middleton, commander of VIII Corps, dispatched Clarke and CCB to support Jones. By 1030 on 17 December, Clarke had arrived; by 1400, Jones turned to Clarke and said, “You take command, I’ll give you all I have…I’ve lost a division quicker than any division commander in the U.S. Army.”15

Clarke began the Battle of St. Vith as a traffic cop, personally directing units into St. Vith throughout the night of 17 December. Captain Dudley Britton of the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion commented, “That day I saw the highest ranking traffic cop I have ever seen.” Clarke’s CCB had to force their way upstream of retreating units; his opposite number, General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel, also spent that night as a traffic cop, organizing the build-up for attacking St. Vith.16

Clarke employed CCB of the 7th Armored at St. Vith just as he had CCA of the 4th Armored at Arracourt. Manteuffel believed there was a full tank corps at St. Vith. In reality, what he saw was the same battalion of tanks constantly moving between positions. On 18 December Clarke was ordered to hold St. Vith for three days. These orders forced Clarke and his command to face overwhelming odds while coordinating units from several divisions during a confusing command situation (every other general present, deferring to him, were superiors in rank or time in grade).17

German units forced the 106th’s two surrounded regiments to surrender on 19 December. On the night of 20-21 December, Germans penetrated into St. Vith, though CCB still held the surrounding area. German vehicles flooding into St. Vith caused a giant traffic jam in a combat zone, ironically becoming victims of their own success. 21 December marked the fifth day of CCB’s defense of St. Vith, and the fourth of three days they had been ordered to hold out. Clarke’s troops were beyond exhausted.18

On 22 December, Major General Matthew D. Ridgway, commander of XVIII Airborne Corps, ordered the 7th Armored Division to remain near St. Vith to create a “fortified goose-egg” and fight surrounded, as was happening with the 101st Airborne Division in Bastogne. Clarke reported his force was only about forty percent effective and still engaged. Referencing the 7th Cavalry at Little Big Horn, Clarke commented that the plan for the 7th Armored looked “like Custer’s last stand to me.”19

Ridgway was overruled by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Ridgway’s superior officer. “You have accomplished your mission…it is time to withdraw.” The 7th Armored Division had held for a full week when asked to hold three days. “They can come back with all honor… They put up a wonderful show,” Montgomery said. At 0500 on 23 December, Hasbrouck informed all units, “It will be necessary to disengage, whether circumstances are favorable or not, if we are to carry out any kind of withdrawal.” By 1000, at the tail end of his column, Clarke’s jeep roared across the escape bridge at Vielsalm, which was blown behind him. The exhausted brigadier general fell asleep in the passenger seat.20

Manteuffel met Clarke twenty years later at an event marking the anniversary of the defense of St. Vith. In a later letter Manteuffel wrote, “The brilliant, outstanding delaying action around St. Vith was decisive for the drive of my troops and for the Sixth SS Panzer Army too…the battle of St. Vith was of greatest consequences for the two armies—and the whole German offensive. In the end St. Vith fell, but the momentous main drive of the LVIII Panzer Corps had been destroyed.” In Eisenhower’s Lieutenants, Russell Weigley asserted that “more perhaps than any other… it was the battle of St. Vith that bought the time required by Allied generalship to recapture control of the [Battle of the Bulge].”21

Clarke’s CCB was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation (now known as the Presidential Unit Citation) for their actions between 17 to 23 December. Clarke himself was awarded a Bronze Star with “V” device. He refused a higher decoration, believing that too many of his officers and men had no opportunity to have their own deeds recorded. “I am [prouder] of that Bronze Star than of my DSC and three Silver Stars. I believe I deserved it more than the other decorations.”22

Colonel Jerry Morelock, in his book, Generals of the Ardennes, a study of American commanders in the Battle of the Bulge, had this to say of Clarke’s actions in the battle:

Clarke’s most dominant leadership characteristics…was a supreme and total self-confidence…he never doubted his own abilities, nor was he ever shy about stepping forward to take charge or expressing his opinion about any military subject…Without much guidance he knew what needed to be done; drawing on his combat experience, he knew how to go about doing it; he projected self-confidence and competence which inspired his staff and troops; and, perhaps above all, he saw it through to a successful ending.23

After Clarke led CCB to retake St. Vith a month later, he was flown to England to have his gall bladder and thirty-eight gallstones removed; Clarke had delayed treatment and had self-medicated the pain with high amounts of codeine for months. He returned on 1 June 1945. On 20 June he was reassigned back to the 4th Armored Division, this time as commanding general, but he only held the position for a few days. Clarke was requested by General Douglas MacArthur and sent to the Asiatic-Pacific Theater of Operations during the planning for the invasion of Japan, to serve as an engineer officer. He was building a logistics brigade for the invasion of Japan, a role he served in from June to August 1945 when World War II ended.24

After Japan surrendered, General Devers, now commander of Army Ground Forces (AGF), appointed Clarke to the position of Director of Armor at the Pentagon, but General Marshall did not like the idea and ordered Devers to find a different role for Clarke. “So, being Director of Armor only lasted days…[I was] put into the Plans Section,” recalled Clarke. Within a few months, AGF moved to Fort Monroe, Virginia, and Clarke became Deputy G-3 (Operations). A few months later, he became the G-3 until the beginning of 1948.25

As the AGF G-3, Clarke changed the Army school system, modernizing it and adding the Armed Forces Staff College, the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, and the National War College. Clarke helped design the postwar armored division, advocating a flexible combat command and separate battalion organization. In early 1948, Devers assigned Clarke to the Armored School at Fort Knox, Kentucky. There, Clarke rebuilt the facilities, reorganized the faculty, and introduced new techniques. In August 1949, Clarke was assigned as commanding general of the 2d Constabulary Brigade at Munich, Germany. He left the Armored School a model for others to observe and emulate.26

Major General Isaac D. White, U.S. Constabulary Commander, instructed Clarke to create a Constabulary Noncommissioned Officers Academy, which opened on 15 October 1949 with Clarke as commandant. The Army’s NCO academies were later based on this first NCO school. Clarke took an opportunity that year and integrated the 15th Constabulary Squadron. Understrength, the unit needed more manpower to accomplish its duties. Clarke had commanded black troops before back in 1929 and praised the black logistics men who kept 4th Armored rolling during World War II. He knew them to be effective soldiers and considered segregation “not an effective use of manpower.” Clarke split a black infantry company up and reassigned its personnel to the squadron, with a handful of black men per platoon. Clarke wrote of it, “Acceptance was of a very high order by all concerned.”27

At Christmas 1950, Clarke was informed he was to become Chief Engineer, United States Army Europe (USAREUR). Clarke immediately applied for a transfer to Armor; in March 1951, he reactivated the 1st Armored Division at Fort Hood, Texas. Previously poor relationships with local Texans improved dramatically under his leadership, partially due to Clarke’s policy of troops assisting in civilian construction projects instead of make-work assignments. Clarke had to say of this: “The worst thing to discourage soldiers is to waste soldiers’ time doing nothing.” Clarke was promoted on 20 June 1951 to the rank of major general. In the same year, “I integrated the [1st Armored Division] without authority, and it worked so well the Army took the credit for it, which is alright with me.”28

On 10 April 1953, Clarke was sent to South Korea to command I Corps in the conclusion to the Korean War; he was the final wartime commander of I Corps. On 23 June of the same year, Clarke was promoted to lieutenant general. Of his time in Korea, Clarke said, “I don’t think that I…added anything to my prestige commanding a Corps in Korea…My only instructions were to hold what you’ve got.” Among the actions fought during his command were both battles for Pork Chop Hill and the Battle of the Nevada Complex. He made a much greater difference in the years following the Korean War.29

Immediately after the Korean War ended, Clarke established an I Corps NCO academy in South Korea. Clarke next commanded X Corps and served as deputy commander of Eighth Army. He organized and trained the First Republic of Korea Field Army to take over after him. Clarke’s troops rebuilt schools, hospitals, and public facilities around Seoul. These efforts became part of Armed Forces Aid to Korea. General (later Prime Minister) Chung Il Kwon cited Clarke as “the greatest benefactor of the Korean army.”30

On Christmas Day 1954, Clarke was named Commanding General, U.S. Army, Pacific. Two years later, in 1956, Clarke became Commanding General, U.S. Seventh Army, in West Germany. For American soldiers, being guests in the nation and a defense force for Europe rather than an occupation force was proving difficult to adjust to. “Twice I was sent to take the next higher command for one purpose,” Clarke said in 1982, “and that is, ‘He’s good in public relations.’”31

“The American soldier didn’t know why he was here,” concluded Clarke. He immediately, and effectively, went about altering the perception of American forces in Germany. Clarke initiated random surprise exercises, known as “Lariat Advance” orders for the whispered codename said on the phones to initiate them, which woke up 200,000 officers and men to be at the East-West German border within two hours. He described the force shaped during this time as “the first ‘pentomic’ army…designed and organized and equipped to fight on an atomic or nonatomic battlefield.”32

After seven years straight of overseas duties and having only a few months in the Pentagon to his name (two ranks and more than a decade prior), on 1 August 1958, Clarke pinned on a fourth star. He then took the reins of U.S. Continental Army Command. In October 1960, Clarke was informed that the day following his sixtieth birthday he would be going into mandatory retirement. President Eisenhower delayed the retirement and ordered Clarke to West Germany once more, this time as commander of USAREUR, on 20 October 1960. Additionally, Clarke was to command Central Army Group, a NATO command.33

Clarke’s career had prepared him well for his final position. He had extensive experience commanding foreign troops in the Korean War and previous stints with NATO units in Germany. He was keenly aware of the importance of public relations and looking out for the needs of his soldiers, American and allied alike. He not only had the five divisions of Seventh Army, but also the First French Army and the II and III West German Corps.34

Under Clarke’s command, USAREUR became the largest overseas formation deployed in peacetime, at over 250,000 uniformed personnel and 100,000 civilian employees. Clarke ensured the Soviets knew the accurate numbers. “These fellows are very realistic,” Clarke asserted and added, “They don’t go charging in to fight without odds [on their side]. And their intelligence branch might have missed counting some of our men. I don’t want a war to start by mistake.” In August 1961, the Berlin Crisis began. Clarke ordered the creation of the Berlin Brigade on 1 December 1961 to establish a recognizable Army presence inside of West Berlin and show that NATO would not abandon the city.35

Clarke’s sixty-first birthday fell on 29 April 1962. On 25 April, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Lyman Lemnitzer pinned Clarke’s third Distinguished Service Medal on his chest for his service in Germany between 1954 and 1962. On 30 April Clarke concluded his active service, and on 1 May entered the list of retired officers.36

At the age of sixteen Clarke lied about his age to enlist as a private in April 1918; he retired on his sixty-first birthday in 1962, the third- highest ranking officer in the Army at that time. He had been a general officer for seventeen years. Throughout his retirement, he continued to write articles for service journals on a myriad number of Army topics and published his book Guidelines for the Leader and the Commander in 1963; it was translated for use by NATO forces. His direct service, however, was not over.37

During Christmas, 1967, General William Westmoreland, commander of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), invited Clarke to visit South Vietnam and officially assess the situation. Among those receiving him was his former subordinate, General Creighton Abrams, Westmoreland’s deputy at MACV, who was hosting Clarke as a house guest in Saigon when the Tet Offensive erupted. Clarke’s following report was shown to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Clarke asserted that Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, in equipping the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) with obsolete weapons and equipment, reduced the ARVN’s effectiveness to that of a police force. “If we’re going to Vietnamize the war…he needs to know he has as much firepower as the northern fellow. Otherwise, he’s going to lie low in the bushes.” Clarke was invited to Vietnam again at the request of President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu in August 1969.38

On 23 April, 1970, President Richard M. Nixon established a volunteer army as a national objective. General Westmoreland, now Army Chief of Staff, asked Clarke if he could figure out how to improve recruitment. “One of the major deterrents to recruiting volunteers is the fact the candidate has no adequate choice of which unit he will join,” Clarke wrote. “We can increase enlistments if we give the candidate soldier his choice of unit.” The Army’s Unit-of-Choice program was created from this advice. In 2022, a similar option was enacted, in this case allowing new recruits the ability to select their first duty stations within the United States.39

Clarke then reviewed the quality of domestic training, then went back to USAREUR, as professionalism had fallen greatly in the ten years since he had left. Clarke’s solution was good NCO academies to produce effective NCOs and the elimination of make-work and wasting of soldiers’ time. As predictable as his conclusions were, they were also often the right answer.40

Master Sergeant Edward McGinnis, Clarke’s aide on these trips commented, “In one and a half years, ten years after his retirement, General Clarke accomplished more for the United States than in forty-four years on active duty, and that comes from officers that know he commanded more American and foreign troops than any other general in the history of the United States [up to 1974].”41

In 1980, Clarke and his wife moved to Vinson Hall, a retirement community in McLean, Virginia. Clarke continued frequent meetings with members of the Army War College, providing in-depth interviews. Clarke’s wife Bessie died in 1986. Two years later, General Clarke, suffered a stroke and passed away on 17 March 1988 at Walter Reed Army Medical Center at the age of eighty-six.42

Clarke’s service saw him receive a total of forty-one military, civilian, and foreign awards and decorations. Among them, Clarke earned the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal with two Oak Leaf Clusters, Silver Star with two Oak Leaf Clusters, Legion of Merit, Bronze Star with two Oak Leaf Clusters and V Device, Air Medal, and the Army Commendation Ribbon.43

Clarke’s foreign decorations include: the Fourragère from both Belgium and France; the Legion of Honor (Commander) from France; honorary Companion of the Order of the Bath of the United Kingdom; Croix de Guerre with Palm from both France and Belgium; Grand Officer, Order of the Crown of Belgium; the South Korean Order of Military Merit First Class with Silver Star and Order of Service Merit, First Class; Medal for Service in War Overseas of Colombia; and the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.44

Bruce Clarke was the rare four-star general of the latter half of the twentieth century who spent less than a year at the Pentagon before reaching the rank. Over the course of the seventeen years after his promotion to brigadier general, Clarke held fourteen command assignments. His public relations skills were prized, and his engineering efforts can be credited with effective contributions to the rebuilding of multiple nations. The tactics and strategies Clarke learned and taught mean that, through his establishment of NCO academies and design of the armored division’s post-World World War II organization, he is effectively the founding father of effective tank crew training in the U.S. Army during the Cold War. NCO academies activated under his command continue to form the crux of the powerful NCO Corps. When asked what he wanted to be remembered most for, Clarke answered with, “I can’t look at something which seems wrong without trying to do something to make it right.”45

About the Author

Joshua Cline is a research historian at the Army Historical Foundation. He holds a B.A. in History from The George Washington University. This article is dedicated to the late Dr. Diane Harris Cline (1961-2023).

Endnotes

Endnotes

- U.S. Army Center Bruce C. Clarke Personnel Record; See the information for the entry on General Bruce Cooper Clarke on the NCO Leadership Center of Excellence Website (https://www.ncolcoe.army.mil/About-Us/Hall-of-Honor/GEN-Bruce-Cooper-Clarke/), Last accessed 19 July 2023; See the information for the entry on General Bruce Cooper Clarke by Michael Robert Patterson, as found on the Arlington National Cemetery Website (https://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/ bcclarke.htm), Last accessed 19 July, 2023; Jerry N. Hess, “Oral History Interview with Bruce C. Clarke,” Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. https://www. trumanlibrary.gov/library/oral-histories/clarkeb. Last accessed 19 July, 2023.; William Donohue Ellis and Thomas J. Cunningham, Jr., Clarke of St. Vith (Cleveland: Dillon/Liederbach, 1974), 146, 232-233; Jerry D. Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes: American Leadership in the Battle of the Bulge (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1994), 282.

- Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 283; Patterson, Arlington National Cemetery.

- Francis B. Kish, “Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke, Volume I Part II,” Senior Officers Oral History Program. U.S. Army Military History Institute. https://emu.usahec.org/alma/multimedia/719210/20182022MNBT1036359567F278186I001.pdf. Last accessed 19 July 2023; Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 284; Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 207-08; CMH Personnel Record.

- CMH Personnel Record; Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 284.

- Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 284-85, 333; Ernest Fisher, “Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke,” Engineer Memoirs, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC), 20 July, 1984. https://emu.usahec.org/alma/multimedia/412326/20182022MNBT1036359564F339989I001.pdf. Last accessed 19 July 2023.

- Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 285-86, 333; Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 178.

- CMH Personnel Record; Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 102-04; Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 286.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 23; Patterson, Arlington National Cemetery; Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 334; John Albright, “Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke, Part II,” Interview with Clarke, USAHEC, 13 May 1972. https://emu.usahec.org/alma/multimedia/714524/20182022MNBT1036359561F340681I001. pdf. Last accessed 19 July 2023.

- John Albright, “Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke, Part I,” Interview with Clarke, USAHEC, 13 May 1972. https://emu.usahec.org/alma/multimedia/714525/20182022MNBT1036359561F340680I001.pdf. Last accessed 19 July 2023.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 33, 44-46; Albright, Interview with Clarke, Part II.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 65.

- Hugh M. Cole, The Lorraine Campaign (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1950), 90; Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 288; Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 67-68; Fisher, Engineer Memoirs.

- Bruce Clarke Room, South Jefferson School District; Albright, Interview with Clarke, Part I.

- Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 79, 335; Albright, Interview with Clarke, Part I; Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 83, 84.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 84, 109, 114; Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 275.

- Ellis & Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 97, 101.

- Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 101-02, 304-05; Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 101-02.

- Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 306.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 127, 307-09.

- Ibid., 128, 134; Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 309, 311.

- Fisher, Engineer Memoirs; Hasso von Manteuffel, “Letter to General Bruce Clarke,” USAHEC, https://emu.usahec.org/alma/ multimedia/1670336/20183383MNBT1036362253F0000000284495I014.pdf. Last accessed 19 July 2023.; Russell F. Weigley, Eisenhower’s Lieutenants: The Campaigns of France and Germany, 1944-1945 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1981), 490.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 333-34; Bruce C. Clarke, “Battle of the Bulge – Combat Awards” Army Logistician, 17, no. 1 (1985): 31. (Available online at: https://emu.usahec.org/alma/multimedia/412155/20182022MNBT1036359564F339570I005.pdf). Last accessed 19 July 2023.

- Morelock, Generals of the Ardennes, 321-22, 327.

- CMH Personnel Record; Albright, Interview with Clarke, Part II; Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 144, 147, 255; “Bruce C. Clark, Retired 4-Star General, Dies at 86,” Washington Post, 19 March 1988.

- Kish, Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke, Volume I, Part II; Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 147; Patterson, Arlington National Cemetery.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 149-50, 161, 165, 167.

- Ibid., 169-70, 174; NCO Leadership Center of Excellence Website; Bruce C. Clarke, “Early Integration” Armor (November-December 1978), 29. (Available online at: https://emu.usahec.org/alma/multimedia/412084/20182022MNBT1036359568F339826I001.pdf). Last accessed 19 July 2023.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 175, 177, 187; CMH Personnel Record; Francis B. Kish, “Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke, Volume II Part I” Senior Officers Oral History Program. US Army Military History Institute, 1982. https://emu.usahec.org/alma/multimedia/719215/20182022MNBT1036359567F278181I001.pdf. Last accessed 19 July 2023; Clarke, “Early Integration.”

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 187; Patterson, Arlington National Cemetery; CMH Personnel Record; Francis B. Kish, “Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke, Volume II, Part II.”

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 201, 203.

- Ibid., 212-13; Patterson, Arlington National Cemetery; Kish, Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke, Volume II, Part II.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, pp 214-21; “Gen. Bruce C. Clarke Dies at 86; Ex-Army Commander in Europe”, New York Times, 20 March 1988, 36.

- CMH Personnel Record; Ellis & Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 224, 233, 241; Patterson, Arlington National Cemetery.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 241; Hess, Truman Library Interview; Patterson, Arlington National Cemetery.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 238-39; See “Story of the Berlin Brigade,” available on the Army Heritage Center Foundation website (https://www. armyheritage.org/soldier-stories-information/the-story-of-the-berlin-brigade). Last accessed 19 July 2023; NCO Leadership Center of Excellence website.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 283-85; Patterson, Arlington National Cemetery; Hess, Truman Library Interview.

- Washington Post obituary.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 296-98; Albin F. Irzyk, Unsung Heroes, Saving Saigon (Raleigh: Ivy House Publishing Group, 2008), 75.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 305; Mia Figgs, “U.S. Army Guarantees New Enlistees Duty Station of Choice”, U.S. Army Recruiting Command Website (https://recruiting.army.mil/News/Article/2946486/us-army-guarantees-new-enlistees-duty-station-of-choice/). Last accessed 19 July 2023.

- Ellis and Cunningham, Clarke of St. Vith, 308, 313-14.

- Ibid., 322.

- Washington Post obituary.

- CMH Personnel Record.

- Bruce Clarke Room at Clarke Middle School/High School, South Jefferson School District, Adams, New York

- Kish, Interview of General Bruce C. Clarke, Volume II, Part II.