By Joseph-James Ahern

Within the holdings of the University Archives and Records Center at the University of Pennsylvania are several collections of personal papers, records, and reports that document the history of the 20th General Hospital. They describe the personal experiences of the doctors and nurses who left their careers in Philadelphia to answer their nation’s call during World War II. Most notable are the papers of Dr. I.S. Ravdin, Dr. Harold G. Scheie, and Father Lewis J. Meyers, and the diary of Dr. Robert A. Groff.

In early 1939, the U.S. Army Medical Department saw the need to address its deficiency in the number of deployable field hospitals as the possibility of another world war loomed. Major General Charles R. Reynolds, the Army’s Surgeon General, proposed in March 1939 to revive the affiliated hospitals program that the Red Cross had established during World War I. Under this program, civilian hospitals and medical schools would provide the physicians, dentists, nurses, and support personnel necessary to staff the thirty-two general, seventeen evacuation, and thirteen surgical hospitals. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson approved the plan in August 1939, so that by early 1940, Reynolds began coordinating with various civilian medical institutions. One of the institutions Reynolds approached was the University of Pennsylvania, which had organized and staffed Base Hospital 20 during World War I.1

University of Pennsylvania President Thomas S. Gates presented the letter requesting that the University organize and staff the 20th General Hospital to the Board of Managers of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania on 17 April 1940. The Board voted that the matter should be referred to the Hospital’s Medical Board with two recommendations: first, whatever plan the Board submitted did not handicap the operations of the Hospital Departments; and second, that Dr. William Pepper III, Dean of the School of Medicine, and Mrs. Mary Virginia Stephenson R.N., former superintendent of the Hospital, be consulted. In response to this new request, Dean Pepper responded positively, and he began looking to provide skilled physicians to this new unit, without depleting the teaching staff of the School of Medicine.

Pepper asked Dr. I.S. Ravdin to oversee the reactivation of the unit. Ravdin was appointed chief of Surgical Services for the 20th General Hospital, with Dr. Thomas Fitz-Hugh, Jr., as head of Internal Medicine, Dr. James S. Forrester as head of Laboratory Services, Dr. Thomas J. Cook as head of Dental Services, and Dr. Philip J. Hodes as head of the X-ray department. The officers for the 20th were selected from the University’s Medical School and Hospital. All the male officers and fifty percent of the female officers had either a teaching or clinical appointments prior to the formation of the unit, with the selection process focusing on an individual’s competency and ability to work together in a group. As Ravdin noted, “They were selected for professional competence and their known ability to function harmoniously under pressure. Some, especially chiefs of services and sections were chosen because of demonstrated leadership.” Other University staff members were selected for their demonstrated professionalism and assigned new tasks. According to Ravdin, “a statistician and investment counsel became Medical Supply Officer, and a college president’s secretary, Commanding Officer Detachment of Patients.” The 20th General was staffed by June 1940 and began training on campus. Dr. Harold Scheie, an ophthalmologist, wrote home to his parents on 27 February 1941 that he had received his commission as a captain, but would not be called up until “they expected trouble.”2

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, the Army began activating the affiliated hospitals, with the first units being deployed to the Pacific Theater. While hospitals supplied the officers for the affiliated units, the Army provided the bulk of enlisted men from training units. In March 1942, the War Department authorized the 20th General to enlist men into the Enlisted Reserve Corps to serve upon activation. About eighty-eight men were enlisted consisting of skilled workers, pharmacists, plumbers, cooks, brace makers, medical supply workers, and clerks. Throughout 1942 the Penn unit waited for their orders. On 14 April 1942, Scheie wrote, “They seem to be waiting till they need a large base hospital for we have 60-70 doctors and 120 nurses equipped to care for 2000 men.” On 6 May, Dr. Ravdin informed Dean Pepper that the 20th General had been activated, effective 15 May 1942. The first commanding officer of the 20th was Colonel Elias E. Cooley, who was posted at the Lawson General Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. He was also informed that the enlisted personnel from the 212th General Hospital, then training at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, would be transferred to the 20th General.3

On 15 May 1942, the doctors and nurses of the 20th General arrived at the 30th Street Station in Philadelphia to depart for Camp Claiborne. The station platforms were crowded with about 500 people to see the unit off. Dr. Robert A. Groff arrived at the station about 1950 and went straight to the platform with an anticipated departure of 2030. Instead he noted that the “Station became jammed—platform likewise & could not get nurses & enlisted men on train. Finally, pulled trains to end of platform & by 9:07 pm we were off.” Among the officials there to see the unit off was President Gates, who stated, “We hate to see such good men go…But the sooner they go the sooner we’ll get this over with.” After two days on the train, the 20th arrived at Camp Claiborne at 2120 on 17 May. Upon arriving the nurses were sent to the station hospital in ambulances and the doctors were taken to wooden tents.4 The unit would spend the next eight months in Louisiana training. The first meeting the unit had on 19 May was with Colonel Cooley. After the initial meeting, Groff noted that Cooley “thought the 20th Gen. Hosp. was a pick up unit & was relieved to find that it came from the UofPa.”5

It took time for the staff of the 20th to adjust to life at Camp Claiborne. In letters home to his parents, Father Louis J. Meyer—the unit’s chaplain—commented on his living conditions. First he noted, “My house is a half tent affair—sort of an enclosed porch effect: wooden floor, wooden railing, wooden frame covered with canvass, and screened all around the whole space is usually occupied by four cots and four soldiers but as chaplain I have it to myself.” He also commented on the weather: “The climate down here is most unusual: one minute pouring rain— tropical rain; next sun is hot; then a cool ocean breeze off the Gulf, which is 250 miles away. It is, however, always balmy and comfortable at night.” By the beginning of July, the 20th had moved to another section of camp and were living in huts. In addition to becoming accustomed to Army life, junior officers were placed on duty at the station hospital along with the nurses. Unit personnel also were granted leave to visit nearby Alexandria. Groff noted, “I might say that one almost wears out the arm in Alexandria—the number of enlisted men versus officers must be 100 to 1.”6

Speculation of when and where the 20th General would be deployed was a regular activity. As early as 22 May, doctors and nurses had started a pool as to where the unit would go—with one possibility being Madagascar. By the fall of 1942, the 20th was being regularly put on alert for possible movement. On 13 September, Father Meyer wrote home: “Rumor has it that we will be near some good size city, such as Cairo (Egypt). Maybe the East coast of Africa; maybe somewhere in the Pacific.” He added, “This latter I’m hoping for.” However, while other units were shipping out, the 20th General remained at Camp Claiborne. Father Meyer lamented, “Our 20th General Hospital group sits around waiting for the word ‘go’. For the third time the men have been told to get ready; we are ready, but nothing happens. They cannot go far away from camp. Just wait. Our commanders seem to be sure we will be out of here before October 1st. Strange to say they really want to go. They want to get it over with; to get down to business.”7

Finally in December, deployment orders came for the 20th General Hospital. More than a week after Christmas, which included a special Christmas dinner with turkey, gravy, and all the trimmings, the unit boarded two trains heading west on 5 January 1943. The nurses on one train went straight to Long Beach, California, while the officers and the rest of the hospital staff went to Camp Anza in Riverside.Writing home on 10 January, Scheie noted, “From day to day we do not know how long we will have but it will be short.” The unit would remain at Camp Anza for two weeks. On 19 January, they set out for the Port of Embarkation and arrived at the port of San Pedro shortly after midnight.8

The 20th General Hospital’s destination was the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater, an area larger than the continental United States, prone to extreme weather, and home to several tropical diseases. From California, the unit sailed to Australia and then Bombay (present-day Mumbai), India. Groff wrote about the voyage in his diary. On 20 January, the ship pulled away from the dock by 2000. Officers were assigned to staterooms with four to a room. A wartime crossing had its restrictions: “All lights in our room go out so that we have to dress and undress in the dark. We are allowed out on deck until 10 o’clock PM, but no smoking is allowed after orders for darken ship goes into effect.” The ship crossed the equator on 26 January “with much hilarity as is custom put on by the Navy.” By 6 February they had reached the port of Wellington, New Zealand. “At 10:30 we were off boat and on land for the first time in 10 days.” The 20th General was “…treated…royally.” Eleven days later they arrived at Fremantle, Australia, to begin the second part of their voyage.9 From Fremantle they sailed on 20 February for India, arriving on 4 March. “Exactly 41 days from L.A. Everybody was out on deck.” The next day the 20th General disembarked and learned their destination. The nurses were sent to Pooma, while the rest of the unit headed to Deolali near Natzik.10

From Deolali, the 20th General arrived at Assam on 21 March, with the main group arriving on 22 March. Ravdin noted, “The first view of the hospital was something never to be forgotten. We splashed out of the trucks into nearly six (6) inches of soft slippery mud. It was a raw day, with leaden clouds and a driving rain.” The area the hospital would be situated in was surrounded by jungle, tea gardens, and small native dwellings. The Dihing River flowed to the north, and the Namdang was situated to the northeast. For transportation, the Ledo Road cut through the southern part of the area, while the Assam Railroad to Ledo ran through the northern part.11

The hospital site was spread out over more than a square mile, and constructed of bamboo buildings that provided inadequate protection from monsoons. Colonel Cooley set the unit to building paths and draining the area. New bashas (Assamese huts made of bamboo, leaves, and grass) were constructed to provide wards, warehouses, and messes. Extra land was claimed from a section of the jungle to the north between the railroad and the river to build a surgical section. Next, the staff built bashas for male officers’ quarters. It would not be until the fall that adequate quarters were built for the nurses and female personnel. Most of the living quarters consisted of bashas with leaf roofs. These kept the quarters cool, but they became damp and mildewed during the monsoons. In February 1945, these would be torn down and replaced with tents that slept 4-8 personnel with brick floors, waterproof canvas, and British-type fly tops to prevent them from getting too hot. The surrounding area the hospital served consisted of Chinese, Indian, English, and American personnel. At midnight on 8 April 1943, the 20th General Hospital relieved the 98th Station Hospital.12

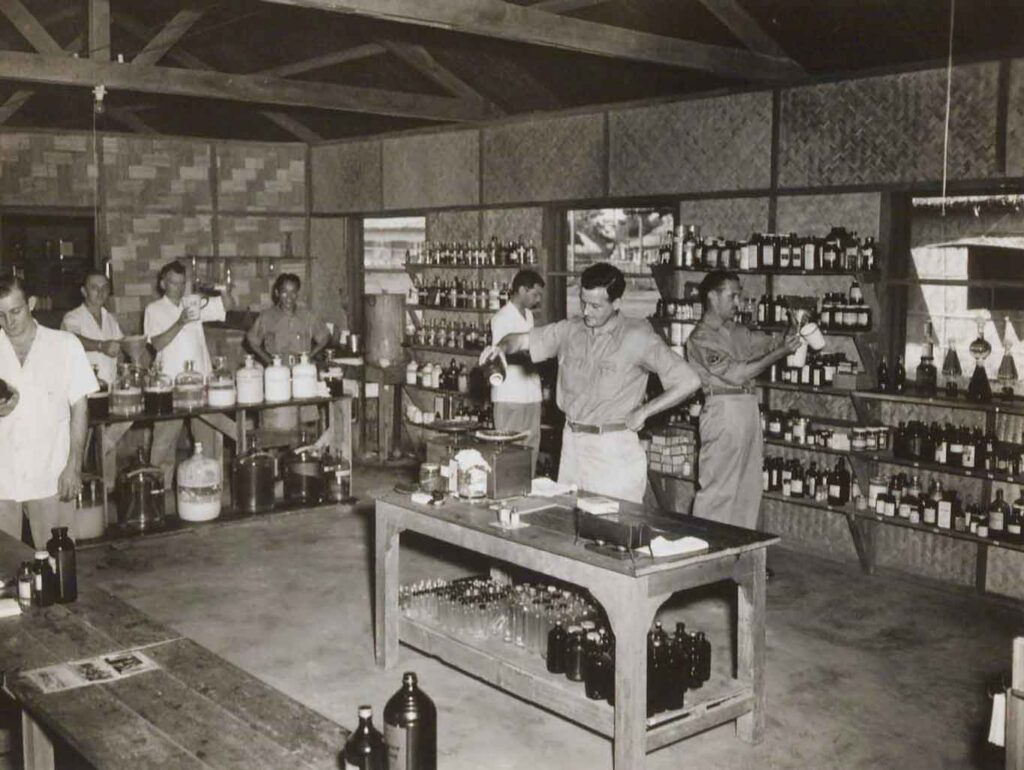

The 20th featured a laboratory, radiological service, dental clinic, outpatient clinic, blood bank, photographic department, and a chapel.13 Rations were another issue facing the 20th General. For the first few months, 20th personnel were issued British rations consisting of corned beef, hardtack biscuits, and tea (no coffee). What American rations they did have were canned. This led to weight loss among all members. To supplement the rations, hospital staff started a garden in November 1943 using local seeds. While the first crop had a low yield, the second year was a success thanks to women from Philadelphia led by Marie Rogers Gates, wife of the University of Pennsylvania’s president, who raised funds to obtain seeds for the garden, including cabbage, bell peppers, radish, lettuce, spinach, beans, cucumbers, cauliflower, and onions, to name a few. Additionally, hospital staff began raising local pigs fattened on the swill from the hospital.14

The 20th General Hospital’s second year in India would be a transitional one. On 13 November 1943, Colonel Cooley was ordered to a new post in Delhi; Lieutenant Colonel Ravdin assumed command, and Major John P. North became the new chief of Surgical Services. During 1944, 139 buildings were constructed of which forty-four were latrines, part of an effort to move them away from the hospital wards. An air- conditioned ward was built primarily to treat scrub typhus patients. All this construction took place while the 20th handled an influx of patients. In July 1944, the 20th General was authorized as a 2,000-bed hospital.15

When the 20th General relieved the 98th Station Hospital in April 1943, it treated 236 patients in the wards—122 American and 114 Chinese. In the following eight weeks, the number of patients gradually doubled.16 In a 12 May 1943 letter, Dr. Scheie noted, “Everything here is buzzing with activity. Our work and everything is extremely interesting at least for the time being.” Over a month later he wrote, “We are receiving more patients all the time. Heaven knows what the limit will be.”17 The hospital reached its peak patient population a year later on 7 August 1944 at 2,562. Unlike the previous year which saw mostly Chinese soldiers treated for malaria, 1944 saw an increase in American soldiers with battle casualties, requiring a higher level of treatment and lab work. In 1944 alone the Surgical Services treated 3,800 battle casualties in addition to the load of surgeries sent from other station and general hospitals. By 1 August 1945, the 20th General admitted a total of 50,232 patients, of which sixty-five percent (32,665) were American. In addition, the 20th treated 325 Japanese prisoners of war and a small number of British casualties. Despite the best efforts of the medical staff, there were 529 deaths at the Hospital (179 American, 328 Chinese, and 22 Japanese POWs). Of the American deaths, sixty-six were from disease, eighty-eight from non-battle injuries, and twenty-five from battle casualties.18

Malaria appeared soon after the 20th General arrived in India with cases reaching into the thousands. In the first eight months, the 20th received over 10,000 malaria cases. Scrub typhus was another medical problem in the CBI Theater as there was no vaccine. Nevertheless, the staff of the 20th General made significant contributions to the medical literature with papers on the treatment of scrub typhus.19

To manage patients, the 20th’s staff developed the unit ward system under Lieutenant Colonel John P. North. Two or three contiguous wards were designated as a unit for receiving specific types of surgical cases. One ward was the master ward—primary care for seriously ill patients—with the majority of staffing and administration here, along with one admission book, narcotic registry, and a complete roster of patients. This allowed for consistent patient care and prevented difficult cases from being passed on to another ward. Basic housekeeping tasks were performed by ambulatory convalescents, with two wards comprising an active and convalescent ward. This system provided for increased professional and administrative management of patients. A benefit of this setup was that the patients took pride in their ward. As Ravdin noted, “They became loyal to the ward officer, nurses and corpsmen on duty there and showed pride in their policing of the area, the housekeeping of the wards and in the construction of useful improvements about the building.” Following the CentralBurma Campaign, the 20th started a reconditioning program. This was designed to help wounded soldiers recovering from injury or illness regain muscular or vascular tone prior to being sent back to their units. The program included in-bed exercises one to two days after surgery and outdoor calisthenics.20

Air control was an essential part of the evacuation process for the 20th General. The difficulty of evacuating patients from the jungle led to the construction of a small airstrip for liaison planes twelve miles away. Eventually, a modern airfield was built three miles from the Hospital. According to Ravdin, “Without this field we could not have functioned and evacuations would have been impossible.” The 803d Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron initiated evacuations from the combat zone in late November 1943 until 1 December 1944 when the 821st Medical Evacuation Transport Squadron took over. Both used the C-47, being able to accommodate eighteen to twenty-four litter patients. If an area could not accommodate a C-47, smaller, single-engine L-4s were used. Between 6 March 1944 and 14 April 1944, the time between injury at the front and admission to the Hospital in the rear averaged forty-eight hours for Chinese soldiers. For American troops, being frequently isolated and requiring longer litterage, the average was 4.5 days. About thirty-six percent of American casualties reached the Hospital seven days after injury. To improve evacuation time, twenty air clearing stations were established in northern Burma. With the supply of forces reliant on cargo planes, it meant that wounded could be evacuated even if dedicated air ambulances were full. About 4,000 casualties—Chinese, American, and British—were flown out of northern Burma in May 1944 alone. As a result, the previous delay from wounding to reaching a hospital at Ledo was reduced from 4-5 days to 1-2 days. In June 1944, about 3,800 battle casualties arrived at the Ledo Air Strip. During the Battle of Myitkyina, twenty-five percent of casualties arrived at the 20th General on the day of injury.

Air evacuations, however, were not without risk. On 18 May 1944, an ambulance plane landed without authorization at the Myitkyina Air Strip. About to depart loaded with casualties, the pilot was forced to abort his take-off as a Japanese Zero came in low over the field, strafing the plane and dropping bombs. One patient was killed, while the flight surgeon, nurse, technician, and radio operator were wounded. Despite being riddled with bullets, the plane managed to deliver its patients later that day.21

The efforts of the men and women of the 20th General did not go unnoticed. Captain Jerome H. Ross, who was evacuated from Burma to the 20th with a case of mite typhus, attributed his recovery to the care he received. He wrote, “The meticulous attention to each patient, the constant care soon fills in where medicines fail. I can but humbly say that I am most thankful to have been fortunate enough to have been sent here.” Army Surgeon General Norman Kirk observed that the 20th General, “…by its intelligence and skill it reduced the mortality of our Troops to a record unequaled by any nation in the annals of war.” In recognition of the care Chinese soldiers received, Lieutenant General Liau Yaou-Sian, commander of the Chinese Sixth Army, presented the 20th General Hospital with a flag.22

One of the American combat units to come under the care of the 20th General was Brigadier General Frank D. Merrill’s 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), better known as “Merrill’s Marauders.” In addition to combat injuries, the unit’s long jungle treks resulted in numerous cases of exhaustion and disease among the troops. The casualty rate among the Marauders was 2,400 of its original 3,000 troops, of which 2,000 were attributed to disease. The staff of the 20th General followed the operations of the Marauders with great interest, having watched the unit march up the Ledo Road and caring for its sick and wounded. The unit’s attack on the Myitkyina Air Strip on 17 May 1944 resulted in a considerable increase in causalities treated at the 20th. Ravdin noted, “Most of them came through our hospital, gaunt, famished, grimy, tattered and worn out physically and psychologically. Their unfavorable physical condition made recovery from infection, disease, or wounds more difficult.” Merrill himself was a patient at the 20th General, having suffered a heart attack in the field. Upon leaving the CBI Theater on 7 June 1944, Merrill wrote to Ravdin, “I understand fully that we have added a great amount of work to an already overworked staff, but it has always been comforting to know that when my sick and wounded reached your Hospital they were assured of the very best medical and surgical treatment available in this Theater.”23

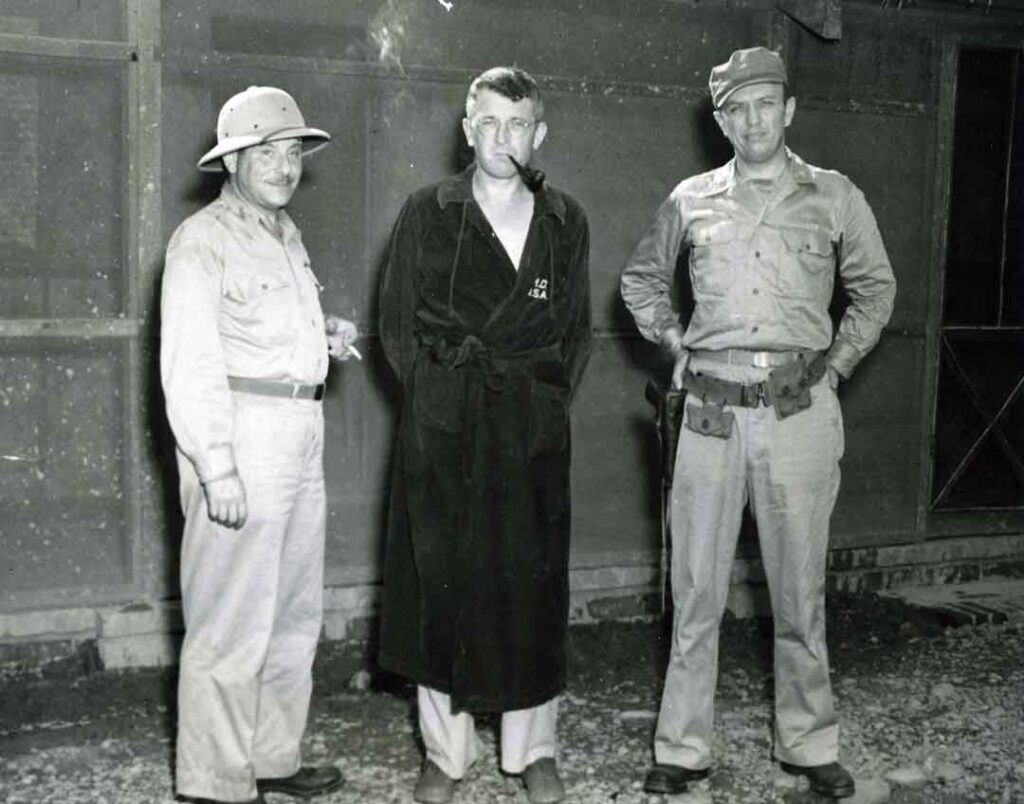

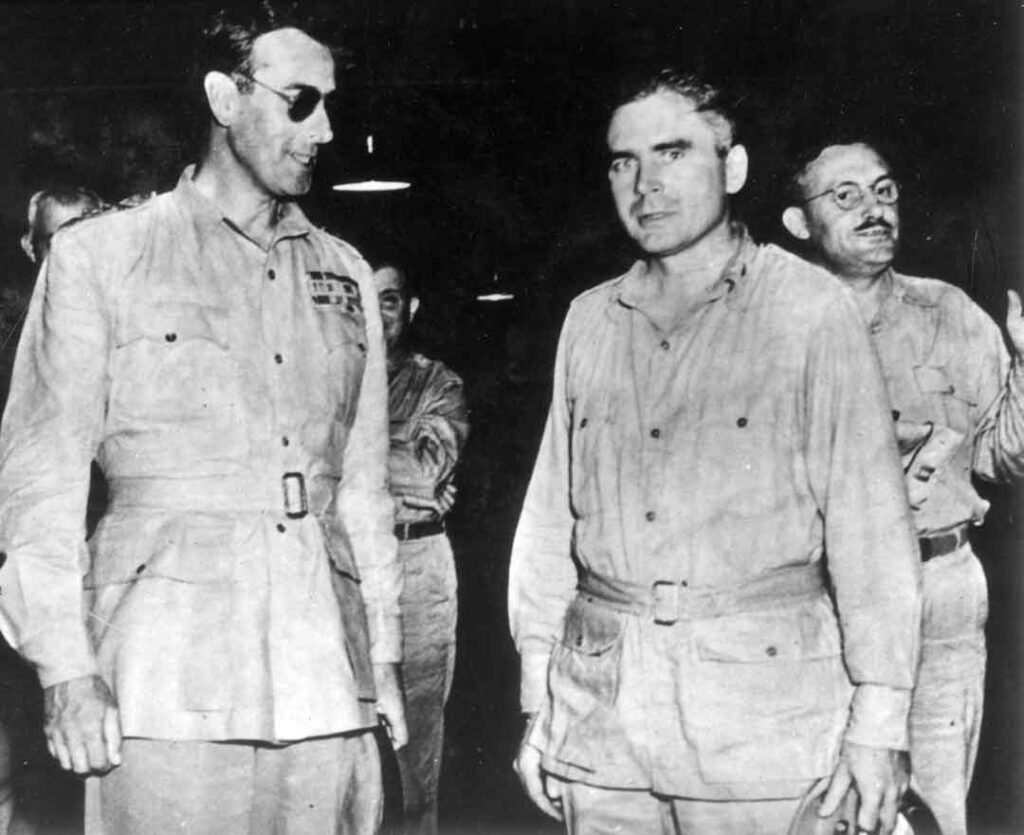

The 20th General also treated Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander of Southeast Asia Command, following an injury to his left eye, which was struck by a branch while driving through the jungle on the Ledo Road. Dr. Scheie was able to successfully save Mountbatten’s eye, which not only made an impression on Mountbatten regarding the clinical skills of the 20th General, but also established a lasting friendship between Mountbatten and Scheie. In recognition of their services, Mountbatten personally presented a plaque to the 20th General noting the excellent treatment he had received during his week there.24

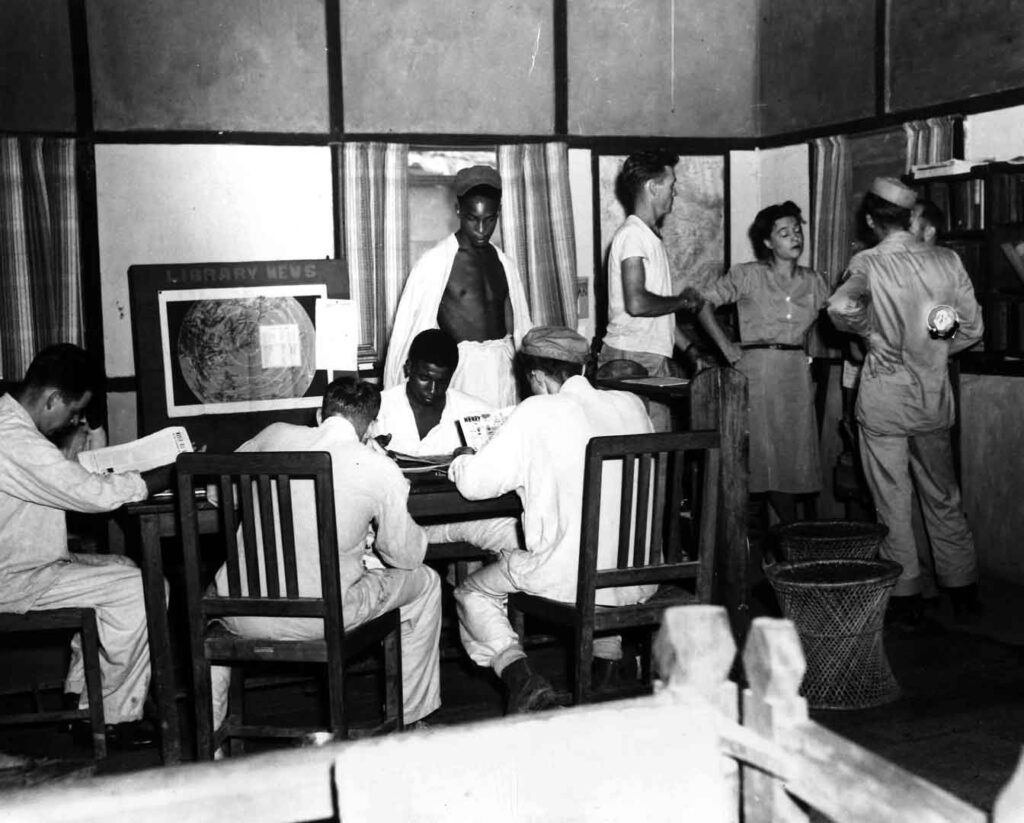

Maintaining morale was an important part of the 20th General’s success. There were no sports equipment or organizations during the first year in theater. Eventually, an intra-hospital softball league was formed. It was noted that “the games provided an emotional release from tedious and exacting work as well as an opportunity to develop friendships, teamwork, and cooperation among the [enlisted men] as well as officers.” By 1944 four clubs had been formed—one each for the officers, nurses, noncommissioned officers, and enlisted personnel. Each had its own building for parties, dances, and programs. There was even a unit newspaper, Fever Chart, which was started in the summer of 1944. Also in the summer of 1944, actor and comedian Joe E. Brown, actress Paulette Goddard, and playwright Noel Coward entertained the 20th General while touring the area. Movies were a major source of entertainment, with screenings three times a week in the Detachment Area in the open. In December 1944, the 20th received a surprise Christmas gift when nine reels of film arrived containing scenes from home and familiar faces. Courtesy of friends at Penn, the films showed family members and friends. Three reels were for medical men, dentists, and others serving; two were devoted to nurses’ families, and the remaining four focused on personalities and places “well known to all who have been associated with the University’s medical division.” The films were directed and filmed by Dr. Louis H. Twyeffort, who was an instructor in psychiatry at the School of Medicine and an amateur photographer.25

With the end of hostilities in August 1945, the number of American troops in the CBI Theater soon declined. Between 1 October and 10 November 1945, troop strength decreased from about 30,000 to 12,000. Patients at the 20th General Hospital dropped from 709 to 219. In September 1945, Ravdin departed the 20th General to return home, resuming his duties as the John Rhea Barton Professor at the University of Pennsylvania on 2 November 1945. Command of the 20th was transferred first to Lieutenant Colonel Sydney P. Waud for two weeks, then Lieutenant Colonel Warren H. Diesener assumed command on 1 October 1945. Diesener would oversee the closing down of operations. On 10 November 1945, the 20th General Hospital ceased admitting patients, turning the installation over to the 25th Field Hospital. Personnel began to transfer out and the unit was inactivated on 25 November 1945.26

As personnel from the 20th General returned to Penn, they resumed their previous occupations in the Hospital and School of Medicine. Dr. Ravdin continued his career at Penn, becoming an invaluable administrator and surgeon. He would eventually rise to the position of Vice President of Medical Affairs before retiring in 1965. Ravdin would also stay active in the Army, retiring with the rank of major general in the Medical Corps in 1956. I.S. Ravdin passed away on 27 August 1972. Today the main entrance to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania is named in his honor. Dr. Scheie returned to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University’s Medical School, eventually becoming the department chairman in 1960. His efforts to create an independent eye center led to the establishment of the Scheie Eye Institute in 1972, which remains affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania. The dedication of the Institute was attended by Scheie’s longtime friend, Lord Mountbatten. Harold Scheie eventually retired from practice in 1983 and passed away on 5 March 1990. Dr. Robert Groff would also return to the University of Pennsylvania where he would eventually serve as head of the Department of Neurosurgery until 1968. Dr. Groff died in 1975. Finally, Father Louis Meyer was discharged from the Army in 1946 and returned to his pastoral duties, serving at various parishes in the Diocese of Philadelphia until his retirement in 1972. Father Meyer passed away in 1985.

The University of Pennsylvania was interested in keeping the 20th General Hospital as an affiliated unit into the Cold War. However, the new Amendment of Affiliation Agreement the Army sent to the University indicated their desire was for a professional complement training unit that would not be named the 20th General Hospital, nor would it be comprised of solely University personnel. By 1951, the University saw little point in organizing such a unit and dropped the matter.27 The legacy that the 20th General Hospital left behind is one of men and women who provided exceptional medical care to the wounded (both Allied and enemy) in the austere environment of the China-Burma-India Theater and adds to a history of University of Pennsylvania medical personnel providing care to the nation’s soldiers that stretches from the American Revolution to today.

About the Author

Joseph-James Ahern is a senior archivist at the University of Pennsylvania’s University Archives and has over twenty-five years of experience as a public historian in the Philadelphia area. He worked at the American Philosophical Society Library and the Atwater Kent Museum, and was a consulting historian for the National Archives and Records Administration-Mid-Atlantic Region and Pennsylvania Hospital Historic Collections. He is a book reviewer for On Point, Maryland Historical Magazine, and Civil War Book Reviews, and has published in Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences, The International Journal of Naval History, and American Neptune. He received a B.A. in History and an M.A. in Public History from Rutgers University-Camden. His historical focus is on U.S. military and naval history from the Colonial Period through World War II.

Endnotes

- Clayton R. Newell, “Hospitals Go to War: The U.S. Army’s Affiliated Hospital Program in World War II,” On Point: The Journal of Army History 20, no. 3 (Winter 2015): 36-38, 43; Clarence McKittrick Smith, The Medical Department: Hospitalization and Evacuation, Zone of Interior (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center for Military History, 1989), 5-6; George W. Corner, Two Centuries of Medicine: A History of the School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott Company, 1965), 298.

- Minutes, 17 April 1940, Box 3, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Board of Managers Records (UPC 12.1), University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania, hereafter referred to as UARC; Corner, Two Centuries of Medicine, 298-99; Report of the 20th General Hospital 3 April 1943-1 August 1945, By Brig Gen. I. S. Ravdin to the Surgeon General (UPI 491.11), 1-2, UARC, hereafter Report of the 20th General; Scheie, Harold to Parents 1941 February 27, Box 2, FF 8, Harold G. Scheie Papers (UPT 50 S318), UARC, hereafter referred to as Scheie Papers.

- Newell, “Hospitals go to War,” 36, 41; Smith, Medical Department, 141; Report of the 20th General, 2; Scheie Harold to his Parents, 1942 April 14, Box 2, FF 9, Scheie Papers; Medical Council and Executive Committee, 1938-1948, 221 1942 June 1, School of Medicine Faculty Minutes (UPC 2.1) hereafter Faculty Minutes, UARC; Corner, Two Centuries of Medicine, 299; Dibble, John (Colonel, Medical Corps) to Colonel Elias E. Cooley, 1942 May 9, Box 167, FF 18, I.S. Ravdin Papers (UPT 50 R252), UARC, hereafter referred to as Ravdin Papers.

- Philadelphia Record Article, Thomas E. Machella Scrapbook, 20th General Hospital Records (UPC 15), hereafter 20th General Hospital Records UARC; Philadelphia newspapers noted that same night Thomas Jefferson University’s 38th General Hospital also departed the city from the city’s Broad Street Station headed for Texas, and that the unit from Pennsylvania Hospital had departed in January and was already in Australia. “2 Hospital Units to Leave for Army”, Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 May 1942, 8; 15 May 1942, Robert A. Groff Diary, 20th General Hospital Records, UARC, hereafter Groff Diary; 17 May 1942, Groff Diary.

- Report of the 20th General, 3; Newell, “Hospitals go to War,” 36; Dibble, John to Elias E. Cooley, 9 May 1942, Box 167, FF 18, Ravdin Papers; 19 May 1942, Groff Diary.

- Lewis Joseph Meyer attended St. Charles Seminary in Overbrook and was ordained a priest in the Roman Catholic Church in 1923. Louis J. Meyer to Mr. and Mrs. Lous J. Meyer, 14 June 1942, 17 June 1942, 3 July 1942, Box 1, FF 2, Louis Meyer Papers (UPT 50 M612), UARC, hereafter Meyer Papers; Report of the 20th General (UPI 42.11), 4; 22 May 1942, Groff Diary.

- 1942 May 22, Groff Diary; Meyer to Parents, 13 September 1942, 17 September 1942, 1942 October 1, Box 1, FF 2, Meyer Papers.

- Christmas Menu, December 1942, Box 1, FF 1, 20th General Hospital Records; 5 January 1943, 17 January 1943, 19 January 1943, Groff Diary; Annual Report, 1944, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers; Scheie, Harold to Parents 1943 January 10, Box 2 FF 10, Scheie Papers; History of the Roman Catholic Choir, n.d., Box 1, FF 29, Meyer Papers.

- Corner, Two Centuries of Medicine, 299; 20 January 1943, 21 January 1943, 26 January 1943, 6 February 1943, Groff Diary; Annual Report, 1944, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers.

- History of Roman Catholic Choir, 3, Box 1, FF 29, Meyer Papers; 3-4 March 1943, Groff Diary.

- The American mission in the Assam area was to construct the Ledo Road as a replacement for sections of the Burma Road which were under Japanese control. Mary Ellen Condon-Rall and Albert E. Cowdrey Medical Service in the War Against Japan (Washington, D.C.: Center for Military History, 1998), 287, 291; Annual Report, 1944 1-3, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers.

- Annual Report, 1944 12, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers; Report of the 20th General, 9-10, 39, 224.

- Annual Report, 1944, 6, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers; The Radiological Service began on 25 March 1943. The heat Humidity and rain proved obstacles to operating the equipment until a new brick building was constructed in December 1943; the Dental Clinic though lacking modern equipment treated 11,050 patients; the Blood Transfusion Service was set up by Dr. Ravdin and Dr. Forester during its twenty six months of service gave 4,125 blood transfusions ;chapel services where first held in a basha until 7 November 1943 when a new chapel was built for 600 people with both a Protestant and Catholic choir, Report of the 20th General, 183, 184, 195-197, 213.

- A civilian-run Chinese restaurant was opened near the Hospital in 1943 June, Report of the 20th General, 69, 73, 223.

- When originally organized in 1943 April the 20th General was authorized as a 1,000-bed hospital. Annual Report, 1944, 1, 5, 11, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers; Report of the 20th General, 201.

- There was a basic lack of medical care in the CBI Theater. The 20th General was one of three hospitals deployed to India – along with the 48th Evacuation Hospital (Rhode Island Hospital Providence) and the 73d Evacuation Hospital (Los Angeles County General Hospital). Upon arrival the only American troops were from service unites, as the Chinese Army was the only combat troops in India. Newell, “Hospitals go to War,” 42-43; Condon-Rall and Cowdrey, Medical Service in the War Against Japan, 292, 298, 302; Annual Report, 1944, 74, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers; Report of the 20th General, 23, 77.

- Scheie to Folks, 1943 May 12, Scheie to Folks, 20 June 1943, Box 2 FF 10, Scheie Papers.

- Annual Report, 1944, 2, 6, Box 167, FF5, Ravdin Papers; Report of the 20th General, 76, 78.

- Report of the 20th General, 10, 23; Condon-Rall and Cowdrey, Medical Service in the War Against Japan, 306; Annual Report, 1944, 11, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin papers.

- Report of the 20th General, 19-22, 191.

- Condon-Rall and Cowdrey, Medical Service in the War Against Japan, 298, 309; Report of the 20th General, 24-25, 27-28.

- Ross, Jerome H. to I.G., 8 October 1944, Letters of Commendation, 1943-1946, Box 167 FF 12, Ravdin Papers; Corner, Two Centuries of Medicine, 300; “Penn Hospital Unit Honored by Sixth Chinese Army,” 1944 December, Daily Pennsylvania.

- Christopher L. Kolakowski, “Gallantry, Courage, and Devotion to Duty,” Army History no. 116 (Summer 2020): 9-10, 13-14; Condon-Rall and Cowdrey, Medical Service in the War Against Japan, 302, 309-310; Annual Report, 1944, 2, 5-6, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers Box; Report of the 20th General, 27; Merrill, F. D. to Commanding Officer, 20th General, 7 June 1944 Report of the 20th General, 246.

- Report of the 20th General, 244; “Mountbatten Honors Penn Medical Unit,” Daily Pennsylvanian, 14 September 1944, 1.

- Report of the 20th General, 224-225; Annual Report, 1944, 4, 40, Box 167, FF 5, Ravdin Papers; “Movies in India Post Recall Home Scenes”, Daily Pennsylvanian, 20 December 1944, 4; “Gift Extraordinary”, Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 December 1944, 13; “U.S. Hospital Staff in India to See Films of Families,” New York Times, 18 December 1944, 5A.

- History, 1958, 377, 379-380, 386, Box 168, FF 1, Ravdin Papers; Faculty Minutes, 29 October 1945, Faculty Minutes.

- John McK. Mitchell, Dean, to Thomas F. Machella, 12 October 1950, “Contact Information and Correspondence related to the 10th Reunion and 1952”; Harold A. Zintel to I.S. Ravdin, 24 May 1951, “Contact Information and Correspondence related to the 10th Reunion, 1952,” Box 1, FF 2, 20th General Hospital Records.