By Dallas Looney

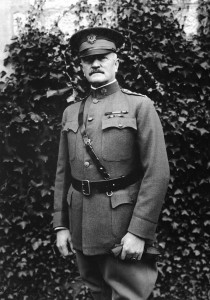

General Gordon R. Sullivan was a man of action and a soldier devoted to serving his country. Amongst many different assignments, General Sullivan was most prominently the thirty-second Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army. His life reflected the values of the American soldier, and he left a significant legacy with the U.S. Army after thirty-six years of service.

Gordon R. Sullivan was born on 25 September 1937 in Boston, Massachusetts, to Russell E. and Penuel E. Sullivan. While he was born in Boston, it was nearby Quincy that Sullivan called home for much of his childhood, and it was there where he felt his first connections to the military through local military parades, personal family connection to the armed forces, and meeting veterans of World War II through his grandfather.

After graduating from Thayer Academy in 1955, Sullivan went on a weekend visit to Norwich University in Vermont. It was there that he set eyes upon the cadets of Norwich, falling in love with the atmosphere and the idea of joining the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC). Sullivan, however, felt he was not the ideal cadet candidate upon his entry as a freshman into Norwich’s ROTC program, but as time went on his performance in academics so improved that he made the dean’s list in his senior year. Leaning upon his previous work in blue-collar positions during his teen years, Sullivan had a respect for the noncommissioned officers who served as instructors in the ROTC program who he felt were less “artificial” during his education. Of particular adoration were the veterans in the program who served in World War II, Korea, and even World War I.

Upon graduating from Norwich in 1959 with a B.A. in History, Sullivan was commissioned a second lieutenant of Armor and sent to the U.S. Army Armor School at Fort Knox, Kentucky, to attend the officer basic course. After completing the officer basic course, he was assigned to 1st Battalion, 66th Armor, 2d Armored Division, at Fort Hood, Texas. While at Fort Hood, Sullivan oversaw advanced individual training of soldiers in his battalion on armored vehicles, including the M48 tank. Other duties included classroom instruction, maintenance, field hygiene, and marksmanship. Sullivan spent the better part of the year learning about platoon leadership. He also became the communications officer and was sent back to Fort Knox and the communications school established there in February 1960.

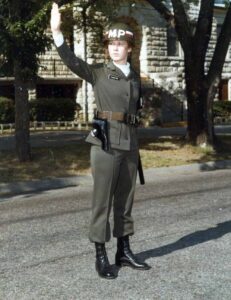

Now a Regular Army officer, Sullivan was assigned to Korea in 1961 to serve with 3d Battalion, 40th Armor, 1st Cavalry Division. Sullivan later stated that this was one of his best assignments in the Army as he was able to put his training into practice in the field. The shadow of the Korean War still weighed heavily upon South Korea during this period as Seoul and the surrounding area continued to bear the scars of war. Moreover, the South Korean government at the time was fragile, with the ongoing threat of coups, along with hostile actions by the North Koreans along the Demilitarized Zone, which forced U.S. troops stationed there to remain on high alert. Still, Sullivan truly came into his own during this assignment at a time when the Army was struggling in many areas, and he came to understand the environment of frontline soldiers firsthand and the challenges they faced.

While Sullivan was serving in Korea, General Maxwell D. Taylor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, sent out a message inquiring about volunteers for a growing conflict underway in Vietnam. Sullivan volunteered to go in what would soon become a major war. In 1962, First Lieutenant Sullivan attended the Military Assistance Training Advisor course at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, before being sent to language school in Monterey, California, to learn Vietnamese. After his education, he deployed to Vietnam in January as an advisor to the 21st Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) Division.

Sullivan served within the IV Corps area of operations in South Vietnam. Lacking any airmobile capabilities, he and other officers used jeeps and boats to move across the Mekong Delta. It was in Vietnam that Sullivan recognized the incoherent nature of the advisory effort, finding the strategic hamlet program ineffective. Facing combat from Viet Cong (VC) guerrillas in the region, one particular engagement that stood out involved Sullivan communicating with nearby UH-1 Huey helicopters that wished to see his unit. When the Hueys closed in, a Viet Cong fighter popped out of a spider hole with a Browning Automatic Rifle and opened up on the lead helicopter. The resulting battle in a pineapple field ended with eighty VC killed. Sullivan, however, was wounded and promptly evacuated to a hospital at Tan Son Nhut Air Base outside of Saigon. Weeks later, Sullivan would be assigned to Military Advisory Command, Vietnam (MACV), working as the executive officer to the assistant chief of staff, J-2 (Intelligence), MACV. Living in a climactic moment in history, Sullivan was witness to the 1 November 1963 coup of President Ngô Đình Diệm’s government by a group of CIA-backed Vietnamese officers. His experience with witnessing the chaos around the summer and fall of 1963 and increasing VC attacks spreading across IV Corps led Sullivan to believe the coup was a critical moment, and not just a changing of the guard.

Sullivan continued to act as an advisor, working with the South Vietnamese Civil Guard and other advisory detachments, an experience he described as challenging. When his tour ended, Captain Sullivan attended the armor advanced course back in Fort Knox. It was there that Sullivan recognized a distinct lack of Vietnam studies in the curriculum, a strange state of affairs given that it was 1964 and the number of advisors in-country was upward of 23,000-plus. Still, U.S. combat units had not deployed to the region yet, so when Sullivan graduated from his course in 1965 and traveled to Washington, he asked to be sent to Germany.

After graduating from the advanced course, Sullivan married Miriam Gay Loftus on 20 June 1965, and the newlyweds soon headed to West Germany for Captain Sullivan’s new assignment with 3d Battalion, 32d Armor, 3d Armored Division, in Freiberg, West Germany. There, Sullivan served as a company commander. In October 1966, Sullivan became the combat arms assignment officer in Heidelberg. Ultimately, the focus began to shift from Europe towards the brewing conflict in Southeast Asia and, as a result, Sullivan’s duties included sending officers to Vietnam. His assignment with U.S. Army Europe (USAREUR) would come to an end in June 1968 when Sullivan (promoted to major in September 1967) returned to the States to attend the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, graduating in June 1969.

Sullivan began his second tour in Vietnam immediately after graduation, serving as a staff officer with I Field Force. Upon returning from Vietnam, he was assigned to the Office of Personnel Operations, Actions Section, Armor Branch, in the Pentagon. He then earned an M.A. in Political Science from the University of New Hampshire and was promoted to lieutenant colonel in May 1974. Once again returning to Europe in January 1975, Sullivan assumed command of 4th Battalion, 73d Armor, 1st Infantry Division (Forward). This was followed by a stint as Chief of Staff, 1st Infantry Division (Forward), from August 1976 to June 1977.

After his tour in Europe, Sullivan attended the Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1978. Reassigned back to Europe, Sullivan, promoted to colonel on 1 July 1980, served as Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3 (Operations), VII Corps, USAREUR, until May 1981. Sullivan then assumed command of 1st Brigade, 3d Armored Division, and then became Chief of Staff, 3d Armored Division, in 1983.

Sullivan served as assistant commandant to the U.S. Army Armor School from November to July 1985. While at Fort Knox, he pinned on a brigadier general’s star on 1 October 1984. His stint at Fort Knox was followed by an assignment as the deputy commandant of CGSC from 1987 to 1988. In July 1988, Major General Sullivan (promoted to two-star rank on 1 October 1987) assumed command of the 1st Infantry Division (Mechanized). After commanding the Big Red One, Sullivan was promoted to lieutenant general in July 1989 and named Deputy Chief of Staff, Operations and Plans, from 1989 to 1990.

In June 1990, General Sullivan gained his fourth star and became the Army’s Vice Chief of Staff, paving the way for his ascension to the Army’s thirty-second Chief of Staff on 21 June 1991. His tenure as Chief of Staff was during a strategic shift in the Army’s mission, as the Soviet Union collapsed and attention turned toward the “peace dividend” expected from the end of the Cold War. As a result, Sullivan was Chief of Staff during one of the largest force reductions in the Army’s history, not just in personnel numbers but also posts and other installations. Without the Soviet enemy on the horizon, the Army’s focus had to shift from preparing for an inevitable conflict with a global superpower to something more nuanced and focused on strategic flashpoints around the world. Sullivan also experienced a critical moment in Army history with the inclusion of digital information in military technology. While the military has always had a close relationship with the latest in computing technology, the early 1990s were a period of significant technological advancement in Army weaponry, vehicles, and equipment. Sullivan had a great interest in Army history, and during his tenure as Chief of Staff, he established a permanent artist-in-residence at the U.S. Army Center of Military History. On top of it all, the Army underwent further developments in expanding recruitment efforts to women and minorities. His time as Chief of Staff encapsulated one of the greatest moments of change in the Army. In addition to his duties as Chief of Staff, from August to November 1993, Sullivan served as the acting Secretary of the Army until the confirmation of Togo D. West, Jr., as Secretary.

General Sullivan’s service as Chief of Staff ended with his retirement from the Army in June 1995. His many awards and decorations included the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, Defense Superior Service Medal, Legion of Merit, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Meritorious Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, Joint Service Commendation Medal, Army Commendation Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, Army Achievement Medal, and Combat Infantryman Badge.

Yet this was not the end of his service for the Army, as he turned his attention towards the Association of the United States Army (AUSA), becoming its eighteenth president in 1998. His leadership of AUSA was marked by AUSA’s significant growth in membership and prominence, as well as ensuring that the organization continued to represent the interests of soldiers, veterans, and Army families. Under his watch, the AUSA Annual Meeting, held each year in October in Washington, DC, grew in size and influence, and became the premier event for the defense industry, Army commands, and organizations that support soldiers. His steadfast commitment to the role of president ended in 2016 as AUSA’s longest-serving president. He was awarded AUSA’s highest honor, the General George Catlett Marshall Medal, for his devoted service to the organization and the Army.

General Sullivan had a long connection to the National Museum of the United States Army. As his tenure as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army was coming to an end, he began to work with the Chief of Military History, Brigadier General Harold W. Nelson, to reactivate the Army Historical Foundation to fundraise for the construction of a national Army museum, which had been proposed as far back as 1814. As President of AUSA, he helped provide valuable AUSA support to AHF and encouraged the Foundation to remain in the AUSA Headquarters building in Arlington, Virginia, until the fall of 2019, when the Museum neared completion. Forming a strong bond between the two organizations, General Sullivan became Chairman of AHF’s Board of Directors in 2015. He ensured that the Foundation’s mission to construct what became the National Museum of the United States Army was seen through its finality, securing funding and establishing strong relationships with partner organizations. The Museum opened its doors on 11 November 2020.

General Sullivan is not just remembered for these great achievements, however, as he served in leadership and advisory positions with various organizations, including the CNA Military Advisory Board; Board of Trustees of Norwich University; Life Trustee of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute; the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Laboratory Advisory Board; the Marshall Legacy Institute; and the MITRE Army Advisory Board. He also published Hope Is Not a Method (with Michael V. Harper, 1996), which chronicled his experiences in downsizing and transforming the Army as Chief of Staff.

General Sullivan passed away on 2 January 2024 in Massachusetts at the age of 86. He will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery on 10 May. We at the Army Historical Foundation thank General Sullivan for his service not just to this organization and its mission, but to his unending service to his country, his family, his fellow soldiers, and to Army history.