Written By: Dr. Sanders Marble

Throughout the history of the U.S. Army, rations are a never-failing source of conversation and complaint. While a tasty hot meal can be a huge morale booster (especially if there’s enough time to relax), repetitive, tasteless food drags at the spirit. This article will look at the history of U.S. Army field rations, the development of nutritional science, and where the Army is pushing nutrition research.

When the United States declared independence, the Continental Congress legislated a daily ration for the Continental Army that consisted of one pound of beef, eighteen ounces of flour, one pint of milk, one quart of spruce beer, 1.4 ounces of rice, and 6.8 ounces of peas.

Flour was often baked into hardtack to travel better. Milk was a nice idea, but it was highly perishable and did not last. Furthermore, there were not enough dairy cows around New York City that could provide over 10,000 pints of fresh milk per day to supply Washington’s army as it was watching British troops occupying the city. It is doubtful that other Continental troops elsewhere received regular supplies of milk. Spruce beer was a mild anti-scorbutic (scurvy-preventative) agent, but, again, the authorized ration was unrealistic—a quart of spruce beer per man per day was too large to be manageable. It is worth emphasizing here that the anti-scorbutic value was useful but not the reason for issuing spruce beer; the concept of vitamins and deficiency diseases did not yet exist.

This ration had bulk and enough calories if the Commissary General could actually supply all elements, but it was vitamin-deficient. As mentioned previously, vitamins were not discovered until the early twentieth century, and even carbohydrates, protein, and fat (as subcomponents of food with differing nutritional effects) were unknown concepts. The main reason foods were chosen for the ration was because they shipped and stored well.

Moreover, troops were expected to get food beyond the ration—by purchase, by foraging, by gifts from civilians, or by growing it themselves if in camp long enough. The Army’s daily ration underwent little change between 1775 and the 1890s, and, in some ways, the Army took a number of steps backwards. Vegetables and spruce beer were eliminated in 1790.

Rum was dropped from the ration in 1832, with coffee added as the replacement. Notwithstanding a small allowance of peas and beans, there was relatively little change. Joseph Lovell, the first Surgeon General, suggested replacing some of the meat with vegetables, but his advice was ignored. It is worth spending a moment explaining why the Army did not waste away from deficiency diseases such as scurvy. First, soldiers were encouraged and expected to buy and/or grow supplements to their rations. Forts had land to grow vegetables, keep cows, and so forth. Troops also foraged away from garrisons at times, either hunting or gathering. In the desert Southwest, surgeons found cactus juice an effective, if unpalatable, anti-scorbutic.

To get the troops to drink it they added sugar, lemon extract, and whiskey, which was probably the key ingredient in getting soldiers to consume it. Furthermore, commutation was allowed. A unit could take the cash value of some or all of its allotted ration and buy other foodstuffs. But these supplements stopped the moment the troops went into the field, and it was back to hardtack and salt meat.

The ration was largely unchanged by the Civil War. Since there were thousands of troops on campaign for months and even years, some nutritional problems did arise, despite some ration changes. In 1861, potatoes (another mild anti-scorbutic, if not overcooked) were added to the ration.

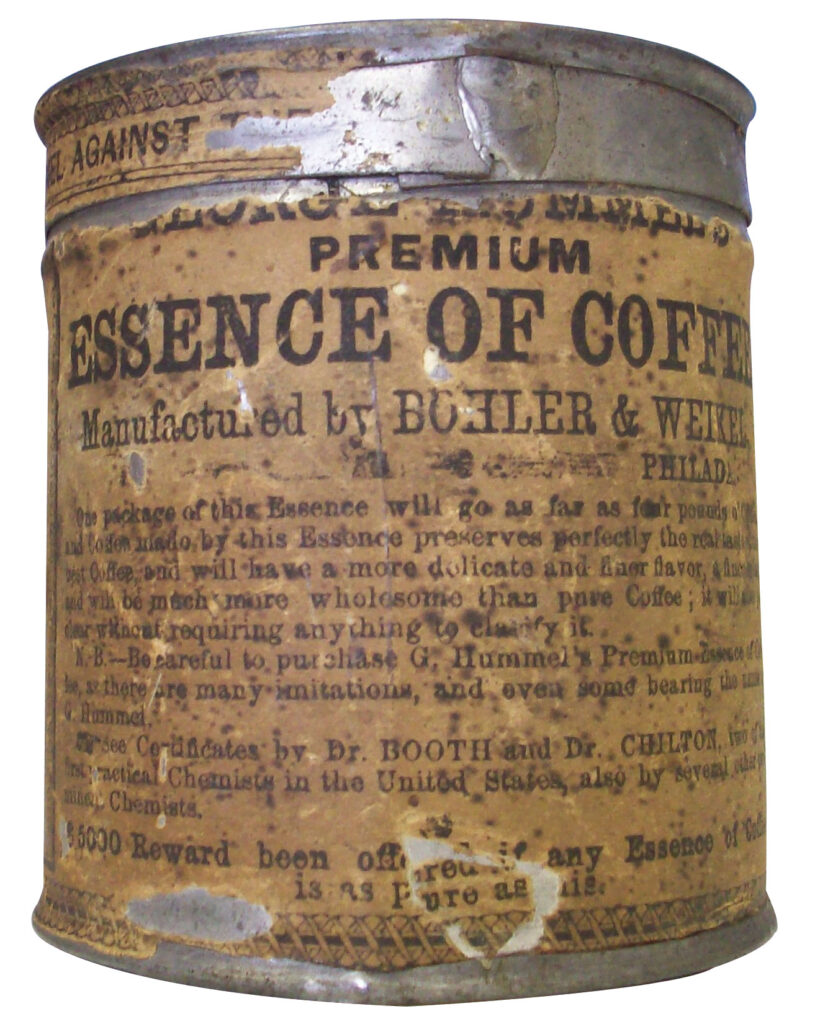

Desiccated vegetables (dried and compressed potatoes and vegetables) were available to Union forces, but soldiers hated them and often referred to them as “desecrated vegetables” or “compressed hay.” Most of the vitamins that had survived the drying process were destroyed by boiling the vegetables too long. To reduce bulk, “essence of coffee” was developed. However, soldiers hated it, too—many said it looked, and tasted, like axle grease and was soon replaced with ground coffee.

Eben Horsford, a pioneering civilian nutritionist, tried to devise a better ration and got the Army to buy some just as the Civil War was ending. Horsford designed his marching ration to be more compact, with roast wheat instead of hardtack and three ounces of cooked-down beef he claimed was equivalent to ten ounces of fresh lean beef. It may or may not have been nutritionally equivalent, but it was an utter disaster. The wheat molded and the meat spoiled, so troops refused to accept it; even dogs would not eat it. Prolonged consumption of the meat/bread ration, albeit with occasional fruits and vegetables, had a harmful effect on the troops. Cases of scurvy developed over winters. Perhaps twenty percent of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman’s troops were listless until fruits and berries became ripe during the Atlanta Campaign.

Elsewhere, there were occasional skirmishes for berry patches, the prize being the berries with their Vitamin C, although troops were more interested in obtaining them for the sugar and flavor. Some Confederate troops, living largely off corn bread and bacon, developed night blindness due to low Vitamin A levels.

After the Civil War, the modest increase in the ration for the citizen-soldiers went away—apparently hard-bitten regulars only needed beans and hay. There was still no official field ration, although an improving canning industry could produce tinned meat and vegetables. These were mainly used as a travel ration for railroad journeys (where troops could not build fires for cooking) rather than in the field. By the 1890s, there were glimmers of nutritional science. Foods were analyzed for carbohydrates, fat, and protein but the Army was still largely concerned with filling the stomach. 1882 regulations allowed the substitution of bread if no vegetables were available; bread was filling, but certainly did not have the same nutrients. In 1890 a pound of vegetables per day was authorized, but seventy percent had to be potatoes because they were cheaper.

By the mid-1890s the Army was looking for a field ration. Confusingly, it was called the emergency ration, reserve ration, haversack ration, or marching ration. The Army did not seek any medical advice when formulating the ration—the goals were compact size, low weight, and use of normal foods. (Pemmican and oatmeal breads were ruled out because they were not foods customary to the troops, an early recognition of the psychology of eating.) The Army tried compressed bread and cooked bacon, but they upset the stomachs of all who tried them, presumably due to bad packaging. By default the Army ended up with uncooked bacon and hardtack. With half the calories coming from pork fat, which cooked out of the ration, its sole merit lay in its portability.

Shortly thereafter, history came full circle a second time and essentially Horsford’s ration was adopted in 1907: three ounces of powdered evaporated beef, six ounces parched wheat, and three ounces of chocolate. This was canned together in a small, flat package that fit into a pocket. However, the Army was still not satisfied and kept tinkering. A “chocolate ration” proved unsatisfactory during the 1916-17 Punitive Expedition into Mexico and was abandoned; it may have melted in the heat. In all this frenzy for a field ration, there was still little to no consideration of nutrition. These rations were intended to tide troops over for a few days, and had 1,200-2,500 calories versus the roughly 4,500 in the garrison ration. The goal seems to have been to keep energy levels up and hunger pangs down.

Nutritional analyses were done on calories, protein, carbohydrates, and fat, but that was all that was done before World War I. By the time the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, the development of nutrition as a science had advanced by leaps and bounds. As already noted, foods were analyzed for calorie content and protein/fat/carbohydrates. These three divisions were a product of the developments in chemistry in the late nineteenth century.

The concept of accessory foodstuffs was propounded in 1906 and the label “vitamines” applied in 1912. (The word would become vitamins in the 1920s when scientists learned that not all were amino acids.) This matched the development of chemistry in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Vitamin A was discovered in 1913 and Vitamin B in 1916. This was far too late for the Quartermaster Corps (still wholly in charge of rations) to make any adaptations.

Operations in World War I rarely required a ration for troops operating independently. In trench warfare, hot food could fairly readily be brought forward to the front lines. Troops were issued a reserve ration (also known as an iron ration, or, from the meat-packing company, an Armour ration). It consisted of hard bread, corned beef, coffee with sugar, and chocolate.

Yet, the Army suddenly began doing more. Surgeon General William Gorgas created a Division of Food and Nutrition to inspect food in camps, to improve mess conditions, and to study ration requirements. Presumably because this was not “real medicine,” it was assigned to the Sanitary Corps, a catchall group established to cover non-physician medical men such as sanitary engineers, psychologists, and laboratory scientists. Since some Army doctors in 1914 still held some absurd notions about health, including the beliefs that ice water was bad for you, eating too fast led to disease, and undigested food rotted in the stomach and led to intoxication, enlisting civilian nutrition experts was a very good idea.

Given the short length of America’s involvement in the war, the Food and Nutrition Division barely got off the ground, but it made a concerted effort to improve the nutritional health of the Army. Vitamin research was started with twelve men in the lab, and Army nutritionists visited camps to advise on foods and cooking.

Since most troops were getting cooked meals at least once daily (and twice daily was frequently possible in the trenches), teaching cooks actually pushed better nutrition into the field. The leading Sanitary Corps nutritionist, Lieutenant Colonel John Murlin, noted the basic ration had too many calories, was not well balanced, and was especially fatty. One wonders what he would make of fast-food restaurants on Army posts today.

In the 1920s, the Quartermaster Corps was still responsible for field rations. While the quartermasters were learning about nutrition, there was still little thought about a field ration or field nutrition. The Reserve Ration was slightly modified from the World War I baseline several times, with different quantities of beef, bread, and chocolate. In 1933, pork and beans was added. Deficiencies in the Reserve Ration were noted, but no action was taken. To be fair, there was hardly the need or the means in the interwar period for such changes. The ration was not being used, nor was there money to fix it. Development work was halted in the mid-1930s “for the principal reason that its infrequent use precludes the necessity for a substitute,” or newer, ration.

Meanwhile, science was identifying more vitamins and minerals: Vitamin C in 1928, Vitamin K in 1934, and Vitamins D and E in 1922. By 1940 fifteen vitamins were recognized, as well as a number of essential minerals. In the 1930s, drug companies were profiting heavily from a public that wanted vitamins. This knowledge was absorbed by the Army, with research focusing on the amounts of vitamins needed. During the mid to late 1930s the Army began looking to overhaul its field rations. The first of the new rations was the D-ration, a fortified chocolate bar that really was not a ration (“The allowance of food for the subsistence of one person for one day.”) but a stand-in for a missed meal. It was so calorie-dense that it could make men nauseous if eaten quickly, and it had to be fortified with Vitamin B1 to help absorption of the calories.

The D-ration was the first of a new family of rations that eventually had nineteen elements at least considered. Most were special purpose, but the big three were supposed to be the A-ration (the garrison ration tweaked for training or field delivery “to meet existing field conditions”), the B-ration (the A-ration but without refrigeration and using canned foods to reduce bulk) and the famous C-ration.

Beginning in 1936, research and testing on the early Field Ration C, or C-ration, was conducted by the Quartermaster Corps. Early batches were grossly low in some vitamins and, due to a math error, the original sample had half the expected calories. Standardized and adopted before full field tests were conducted, the C-ration had some basic problems.

It was bulky, heavy, and awkward, so soldiers could carry fewer and were not inclined to take a full load. To increase manufacturing output, the Quartermaster Corps allowed corners to be cut and accepted a reduction in variety. Theoretically there were equal quantities of three meat rations, but producers found the “meat and hash” to be the easiest to make. As a result, it was over-produced. This may not sound like much, but to a soldier chewing on the same meat and hash for ten days or more, it was a problem, one that could lead to reduced eating and thus reduced nutrient and calorie intake.

The C-ration had problems with its supply of Vitamin C, since the bulk of it in the C-ration came from the lemon juice powder. Since the soldiers did not like it (calling it “bug juice”) and found it more useful for bleaching floors, it points to the risk of putting most of one nutrient in one food item. (The Vitamin C was eventually added to candies and the bug juice dropped.) The C-ration was never tested for palatability, and the design parameters were only “as palatable as possible” over “3-4 days … or longer.” By 1944 there were ten different types of C-ration meat or meat-vegetable menus instead of the original three, and two had already been dropped.

Responding to other troop complaints, the candies were varied with different commercial types. By the winter of 1944-45, help was on the way. Troops had chewed their way through the mountains of 1942-43 C-rations and the supply chain had produced enough of the new versions. Positive, even sometimes enthusiastic, reports began to arrive. Army Medical Department nutritionists had gotten their point across: as long as troops ate it, the C-ration was adequate for nutrients, and the Office of The Quartermaster General was on its way to fixing the production problem.

In contrast, the K-ration was morale-neutral. It was developed to be portable for high-mobility troops, and easily fit into the pockets of paratroopers. It proved more popular in testing (actually being field tested before adoption) partly for non-food reasons—soldiers found the shape was handy. It also used commercial-style components (e.g. Spam and canned chicken) with which GIs felt familiar. It had more calories and vitamins than the C-ration, and was supplemented with more Vitamins A and C. The combat rations had pretty much enough nutrients if the soldier ate them all. While much of the nutritional research in World War II was designed to get all the food eaten, Army nutrionists also conducted research in other areas.

The Surgeon General reestablished a Food and Nutrition unit on 26 August 1940 and received the authority to set Army diet and nutrition standards. Both Army and Navy Surgeons General also pushed the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) to organize civilian nutritionists in 1940.

(This seems to be the first extensive U.S. government sponsored nutrition research.) Research was largely done on conscientious objectors (who volunteered as research subjects) and looked at climatic variations on metabolism and eating, and also vitamin super-abundance. (Whatever Linus Pauling may have believed about Vitamin C, or what advertising at GNC says, there was no evidence that super-abundance helped.)

Studies also found no great loss of vitamins in sweat, that there was no need for salt tablets if meals were eaten (even at ten liters per day of sweating), and that a high-protein diet helped in cold environments. Scientists also tried to find ways to make food more attractive (e.g. keeping dried eggs from browning) that would increase consumption and reduce waste and shipping space.

Uniformed nutritionists traveled to camps, as in World War I, and oversaw the messes. Field tests of new or modified rations were performed, including surveys in the Pacific Theater. In 1944, a Medical Nutrition Laboratory was created directly under the Surgeon General, with approximately twenty-four personnel, replacing the four personnel crowded into the Army Medical School. Postwar studies on Army nutrition showed four problems: 1.)Maintaining the water/salt balance and adequate levels of water, 2.) Getting enough calories, 3.)Adequate protein metabolism, 4.)Maintaining vitamin intake.

The first was not a ration problem; other studies showed there was enough salt in the diet, so the problem lay in water supply and consumption. The second was largely a problem of combat; troops in action did not have the time or conditions to eat enough. The third applied to hospital patients.

Healing is inhibited if protein uptake is low, and patients who were not getting enough protein were given IVs. The fourth was only a very intermittent problem, even in combat. Rations were adequate if eaten, but soldiers who, for instance, did not like the breakfast juices (and thus missed some Vitamin C) or others who worked nights and slept instead of eating lunch, were hardly a ration problem.

There was another lull after World War II in ration development. The reason is fairly simple: the Army had millions of late-World War II C-rations still in depots. (Author’s note: My father reported getting a 1940 or 1941 C-ration on Okinawa in 1962 or 1963, so some warehouses had not rotated their stocks sufficiently.) C-rations were standard in Korea and used in Vietnam.

After World War II, the Surgeon General assumed control over military nutrition and the Military Nutrition Laboratory was transferred from Chicago (where it had been located for convenient co-operation with the Quartermaster Corps’ Subsistence Research Loboratory) to Fitzsimmons Army General Hospital in Denver, and ultimately to Letterman Army Institute of Research in San Francisco.

The Surgeon General also established the Military Recommended Daily Allowance (MRDA). Not until 1958 did a new ration come about—the Meal, Combat, Individual (MCI). Employing lessons from World War II, there was a greater variety of menus, and greater variety of candies, fruits, cigarettes, etc. This let troops personalize their meals and helped to slightly improve morale. (Cigarettes were discontinued in 1972.) The MCI was often mistaken for the C-ration—both had canned elements and both were being used concurrently, so it hardly made a ripple on the soldier’s consciousness.

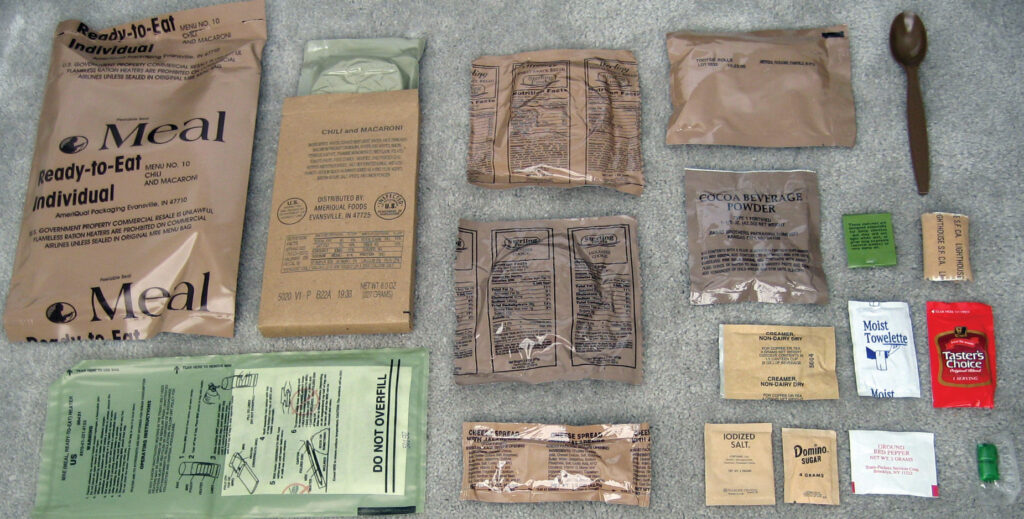

The next generation of ration made a bigger impact. Design work on the Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE) began in 1961, and it was adopted in 1975, finally coming into service in 1981. (While the C-ration had problems, it was developed in roughly three years on a project budget of $300.) As an example of how multiple technologies interact in rations, the development of flat retort packaging (i.e. flexible foil/plastic pouches) meant that lower heat levels could be used to render foods safe for storage; lower heat meant more menu choices were possible; more menu choices meant higher troop acceptance and better field nutrition.

While the MRE does not enthrall everyone, it shows what the Army has learned about keeping its troops happy. Since the MRE is designed to feed soldiers for up to ten days, there had to be a greater menu variety. The Army also rotates menus every two years. Harking back to World War II, there is no use having food and nutrients in the ration if troops do not eat them. Adding hot sauce, developing pouch bread, and including a flameless heater, the desert chocolate bar, better coffee, and commercial candies are all ways to get nutrients where they matter—into the troops. The Army has also continued its basic research on nutrition.

The Nutrition Laboratory at Letterman was transferred to the USDA in 1979 on Congressional orders, but contract research and research at the U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center (Natick) in Massachusetts continues. As the science of nutrition has developed, so has military nutrition research, because military needs do not always match civilian ones. For instance, power bars for endurance athletes are not what combat troops need; soldiers’ energy expenditure is much more episodic. The OSRD civilian advisers and researchers have morphed into the Committee on Military Nutrition Research, a small part of the National Academy of Science, which organizes research the military wants and issues periodic reports.

In the continuing effort to get troops to eat all their MRE (since each MRE is one-third of the MRDA), labeling/graphics/logos are being studied. In today’s consumer culture, we all react to marketing, and it can affect how we eat. The military is also studying how the climate, both physical and command, affects food consumption. Sergeants may be trained to make positive comments about MREs if that helps troops eat them.

The Army also looked into whether it was possible to raise physical performance ten to fifteen percent through foods and/or food supplements. In line with the quasi-pharmaceutical claims for food supplements, research is ongoing in many areas, including the potential of stocking rations with vaccines or vaccine-like drugs; putting precursor chemicals into rations to increase body production of neurotransmitters or histamine; blocking stress-related chemicals; reducing sleep-deprivation effects; and determining what nutrients snacks should have to sustain clear thinking.

As an example, the Army wants a cognitive stamina extender for tired soldiers, especially those performing repetitious duty, such as guards or drivers. Amphetamines have basically been ruled out; amino acids as precursor chemicals are a possibility; serotonin and Modfinil (a narcolepsy drug) are potential options.

But studies have determined that the best way to keep troops from losing focus is caffeine, and caffeine, in the form of coffee, has been in the ration since 1832. Overall, current research has shown that it is not possible to boost troops above 100 percent of normal physical performance through food supplements, but a better possibility is reducing the performance degradation of stress and fatigue.

In conclusion, the Army has transformed its rations as new technologies and sciences have evolved. The technologies are often food storage (tin cans or foil pouches), and the science has paralleled civilian nutritional developments. Concurrently, the Army has learned about the human side of nutrition, about getting people to eat enough and what is good for them. As nutritional research continues, with scientific efforts to improve performance, this will have to be balanced against keeping the food palatable, as both the military and civilians grapple with “nutra-ceuticals” that blend nutrition and pharmaceuticals.