Written By: Andrew Woods

Edgar G. “Eddie” Ireland epitomized the strength of the American citizen-soldier in World War II and has been a role model of determination and optimism ever since. Fresh out of high school in 1942, he was trained as a tanker. In combat, he exemplified the initiative and expertise in gunnery that enabled American tank crews to take on the best armored units the Germans could muster.

During his eight months in the European Theater of Operations, Ireland’s optimistic, “can do” attitude helped him overcome many obstacles—he had five tanks blown out from under him and was the recipient of three Purple Hearts and three Silver Stars. Before V-E Day, Ireland was grievously wounded.

He lost a leg, and, at age 23, relearned how to walk during the two years he spent in Army hospitals. Nevertheless, he married, raised children, and worked hard throughout his life. His gallant actions in war and peace are an inspiration for future generations.

Like many veterans, Ireland recalls the general experience but not the details, of much of the combat he saw, even those times for which he was decorated. Three battles stand out most vividly in Ireland’s memory. He has spoken about them at length in interviews for the First Division Museum’s oral history program. This is the story of these events: his first combat on D-Day; the loss of his first tank at Aachen; and his last action in the Rhineland. Eddie Ireland got a signed consent from his mother to join the Army.

As soon he graduated from Thornton Township High School in Harvey, Illinois, he volunteered to be a tanker, adding, “I took the Armored Forces because I didn’t care for the walking part of it.” With other raw recruits from Camp Grant, Illinois, he arrived at Camp Bowie, Texas, on 17 October 1942. There they joined a cadre from the 191st Tank Battalion to form the 745th Tank Battalion. Ireland was assigned to Company B. Every crewman was trained to perform the duties of the rest of the crew. At first, the 745th was equipped with the M3 medium tank with a 75mm gun in the hull and a 37mm gun mounted in a turret. Ireland was the driver, but he also practiced firing a few rounds from the 75mm gun. He was promoted to technician grade 5, with the title of corporal.

The battalion took part in maneuvers in Louisiana in the spring of 1943. When they returned to Texas, the battalion received M4A1 Sherman tanks, with the same 75mm gun as the M3, but mounted in the turret.

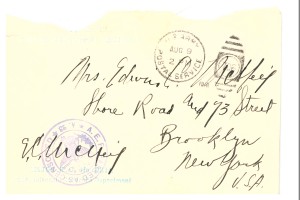

Family members visited Camp Bowie that summer to see the tankers before they left the United States. The men were excited about going overseas as this is what they had trained for.

On 20 August 1943, the battalion sailed for England on the Queen Elizabeth. At the Tank Amphibious Training Center in Beaminster, they received M4A3 tanks, a variant of the Sherman that featured a welded hull. They learned how to waterproof their tanks and conducted trial runs loading and off-loading the Shermans on landing craft. On 21 April 1944, the 745th Tank Battalion was attached to the 1st Infantry Division. A veteran unit of the amphibious assaults on North Africa and Sicily, the 1st Division was preparing to lead the assault on Omaha Beach in Normandy. On D-Day, 6 June 1944, the 1st Infantry Division landed two regiments at Omaha Beach: the 16th Infantry Regiment and the 116th Infantry Regiment, attached from the 29th Infantry Division.

The 16th Infantry was to be supported by two tank battalions: the 741st, comprised of dual-drive (DD) tanks that were to swim in ahead of the assault; and the 745th, which was to follow the infantry on landing craft. Very few DD tanks survived the heavy seas.

However, one landing craft, tank (LCT), carrying a platoon of 741st Battalion tanks, could not lower its ramp to launch its tanks and instead took them all the way to beach.

Ireland’s tank was aboard a landing craft, mechanized (LCM), one of eighteen aboard a landing ship, dock (LSD). The LSD flooded its hold to float the LCMs, each of which carried one tank. Company B and the battalion command group landed in the area of the 3d Battalion, 16th Infantry, on Fox Green Beach at about 1500 hours.

Ireland’s tank, nicknamed Betty, was turret deep in water when it exited the LCM. He tried to open his hatch to take a picture, but the tank ran into a hole as he did so and he got soaked. Fortunately, a shroud on the back kept the engine dry so he could keep the tank going. There was a lot of mortar fire coming in. All the men on the beach were hugging the high tide line or the side of the cliff. Soldiers of the 16th Regiment Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon guided the tanks through the beach obstacles and debris. Three tanks were disabled in minefields.

The tanks moved down the beach and then inland on the single road recently opened by engineers from Easy Red Beach up Exit E1. Ireland’s friend, CPL Edward F. Labno (on another tank), was killed by an enemy sniper. At the top of the bluff, guides from the 16th Infantry led the tanks to positions from which they could engage German pillboxes. Company B was then attached to the 16th Infantry for the attack on Colleville-sur-Mer. As the 1st Division advanced inland through the hedgerow country to Caumont, Company B was attached to the 18th Infantry. After the breakthrough at St. Lô, the 1st Division sped across France and Belgium to reach the Siegfried Line on the German border on 13 September 1944.

The first German city to be attacked was Aachen.

The 18th Infantry’s mission was to seize and secure Ravelsberg and Hill 231, a dominating ridge and hilltop northeast of Aachen. Patrols penetrated a cordon of German pillboxes to link up with the 119th Infantry, 30th Infantry Division, on 16 October 1944, encircling Aachen and cutting the main highway that supplied the city. The Germans counterattacked fiercely to retake the pillboxes on the commanding high ground and reopen the road to relieve their besieged garrison. On 17 October 1944, Company K, 18th Infantry, held a road block to cut the main highway to Wurselen. Company L was tasked to maintain contact with the 119th Infantry.

Enemy machine gun fire from pillboxes pinned down Company L, so Company B, 745th Tank Battalion, attacked the pillboxes in a zone also defended by tanks and troops of the 116th Panzer Division and the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division.

The area was under artillery and mortar fire from both east and west, tank fire from the northeast, and small arms fire from the north.

Ireland later recalled that “We would drive up to the concrete boxes and empty about five rounds point blank into the doorway.” Tank fire proved decisive: the 18th Infantry took 106 German prisoners (many over 50 years old) clearing out the pillboxes.

Enemy tanks, however, remained a problem.

The Betty and its crew were in the thick of the fight, destroying two German tanks, when a shell hit the side of Ireland’s tank, knocking off the right track and immobilizing it. Tank commander SGT Archie Ross told his crew to abandon the tank. The crew ran for a clump of woods. Ross realized they had left the radio in the tank—he feared the Germans could salvage it and learn their frequencies. Ireland volunteered, “I’ll go back and get it.” He scooted back to the tank and got in through the escape hatch on the bottom. Getting the radio out of the tank soon proved difficult, so he smashed it to render it useless.

While Ireland was at the gunner’s station, he looked through the periscope.

He saw a German tank and a halftrack approaching from the road through a tree line downhill, about 300 yards away. Ireland knew what to do: “As soon as you spot the enemy, you let them have it. The Germans would do the same.” The engine was off, but the turret still worked on electricity and the 75mm gun and range finders still worked as well. Ireland lined up the crosshairs and fired, knocking out a Mark V Panther tank. He reloaded and fired again, and again, to destroy another tank and a half-track. He fired the .30 caliber machine gun until it ran out of ammunition. Seeing a German soldier running from the armored vehicles, and with no more machine gun rounds, Ireland fired on the enemy with the 75mm main gun. He then exited the tank through the escape hatch and returned to his crew.

When MG Clarence R. Huebner, commanding general of the 1st Infantry Division, heard of their deeds, he personally presented the Silver Star to each member of the crew: T5 Edgar G. Ireland, driver; SGT Archie C. Ross, tank commander; CPL Alva E. Beck, gunner; PVT William J. Sam, assistant gunner; and PVT Everett Lloyd, assistant driver.

Ireland and his crew soon had another tank, but in the following months, they lost two tanks to mines. An American 500-pound bomb fell short and knocked the tracks off a third tank. In February, Ireland was promoted to staff sergeant.

Now a platoon sergeant, he was second in command of the five tanks of 2d Platoon, Company B, led by 1LT Wilbur F. Worthing. After crossing the Roer River in late February 1945, the 1st Division found itself on the flat Cologne plain stretching east toward an objective along the Erft Canal. With little concealment or cover, the infantry and their supporting tanks relied on night attacks. SSG Ireland felt the tanks should not continue after dark, when their periscopes were useless, but on 1 March, Company B was ordered to continue at night to seize a group of farm houses called Mellerhofen.

2d Platoon attacked at 0015 on the morning of 2 March 1945. The Germans covered their tanks with hay to disguise them as haystacks, so Company B fired white phosphorous to set the haystacks on fire. Silhouetted against burning haystacks and buildings, Ireland’s tank column was lit up like a shooting gallery. Platoon Leader Worthing’s tank was hit three times before it was penetrated and set ablaze. He jumped on the second tank, commanded by SGT William R. Roberts, and continued the attack. Enemy tanks scored hits on this tank and disabled it; SGT Roberts and SGT William J. Sam were killed. The lieutenant jumped onto the platoon sergeant’s tank; Ireland was standing on the side seat in the turret trying to look out.

Ireland’s tank was in front of another burning haystack. At a range of about 300 yards across a field, he saw a Tiger tank emerge from under a flaming haystack and fire its 88mm main gun into the side of his Sherman. The shell ignited both fuel and ammunition, setting both the tank and Ireland on fire. He fell to the floor of the turret, but managed to drag himself up out of the top hatch and off the back of the tank. He bounced onto the roadside and landed in a ditch where water extinguished the fire burning him. Several soldiers, under fire, some badly injured, courageously evacuated wounded tankers from burning Shermans. Four men from Ireland’s platoon were killed; three, including Ireland, were wounded in action; one man was missing. 18th Infantry medics put Ireland on a litter and moved him to the rear.

With Worthing’s and Ireland’s gallantry as examples, 2d Platoon was inspired to regroup and continue the attack. Two hits on the gun shield of another tank disabled the main gun, but it fired its machine gun until all its ammunition was gone. The remaining serviceable tank fired every round of its ammunition, including smoke. One tanker dismounted the .30 caliber machine gun from his disabled tank and repulsed an enemy counterattack until the infantry could reach the scene of action. Infantrymen armed with bazookas got behind the enemy tanks and destroyed them. The Sherman with the disabled main gun and the other tank that was out of ammunition were ordered into the nearby village of Wisserheim. 1LT Worthing then reorganized his platoon with four tanks and held Gymnich. Despite its losses, from there, Company B continued the attack toward the Rhine.

The action at Mellerhofen ended the war for Eddie Ireland. He had lost his right leg below the knee. His badly burned left leg was broken in twelve places. He was hospitalized for the next two years, first at Gardiner General Hospital on the south side of Chicago, then at Percy Jones Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan. Skin grafting saved his left leg; he got an artificial right foot and relearned how to walk. While still recuperating, he courted and married Dorothy Werner, his pen pal from Thornton High School since 1942. Dorothy’s company, Acme Steel in Riverdale, Illinois, made Ireland an electric wheel chair—“It was one of a kind, a big monster with a starter motor powered by two 12 volt batteries,” recalls Ireland. Finally released from the hospital, Ireland was promoted to technical sergeant (E-7) and discharged.

Ireland returned to his job on the Illinois Central Railroad. He went on to work at the Cook County Sheriff’s office. He later managed a Burger King for ten years before going into the hardware business in Hazel Crest, Illinois. Together, he and his wife raised a daughter and three sons: Bonnie, Thomas, who served in Vietnam, David, and Timothy. The Irelands currently reside in Monee, Illinois.

The 745th Tank Battalion held its first reunion in 1955. They still get together every month and have a picnic every year at the First Division Museum, Cantigny Park, in Wheaton, Illinois. Eddie recently appeared on a live, nationwide PBS broadcast, Echoes of War. He has visited Fort Knox and inspired another generation of tankers. Eddie Ireland overcame imposing obstacles on Omaha Beach, outside Aachen, and before Cologne. He overcame obstacles of a different sort in civil life. Optimistic, hardworking, generous and uncomplaining, he was and is an exemplary soldier, veteran, husband, and citizen.