Written By: David Ford

In his final days, Daniel Sickles was described as having lived an “irresponsible and cantankerous” life. For a man who served his country as a politician, soldier, and diplomat, this is a bold yet deeply inadequate statement. Daniel Edgar Sickles was born in New York City on 20 October 1819. Graduating from New York University after studying law, Sickles dabbled in the printing trade, but his lofty career ambitions quickly steered him toward the political arena. Following his admittance to the bar, Sickles obtained a seat in the New York state legislature in 1847. Appointed to a municipal position for New York City in 1855, Sickles gained recognition by securing the land that became Central Park. That same year, Sickles married seventeen-year-old Theresa Bagioli, the daughter of an Italian music instructor.

Sickles forfeited his civic post in New York in late 1855 to join the United States legation in London as its secretary. After serving in London for two years, Sickles was elected to the New York State Senate as a Democrat. He was then elected to the U.S. House of Representatives where he served until 1861.

In February of 1859, Sickles attained nationwide infamy after learning that his wife was engaged in an affair with Philip Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key. In a fit of rage, Sickles shot and killed his wife’s lover in broad daylight in Lafayette Square, directly across the street from the White House. Subsequently tried for the murder of Key, Sickles became the first person in the United States to be acquitted on the grounds of temporary insanity. Sickles’ attorney was Edwin M. Stanton, who later became the Secretary of War in 1862. His wife, Theresa, who Sickles publicly forgave, died a few years later.

As the prospect of Civil War loomed on the horizon, Sickles offered his service to the Lincoln administration in March of 1861. The War Democrat was soon granted permission to raise federal troops. In June 1861, the newly commissioned COL Sickles assumed command of the 70th New York Infantry. Three months later, Sickles was appointed brigadier general of Volunteers and given command of 2d Brigade, known as the Excelsior Brigade, Hooker’s Division, Army of the Potomac. Sickles lead the Excelsior Brigade throughout the Peninsula Campaign. He later was appointed commander of the 2d Division, III Corps, in September 1862.

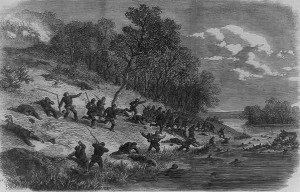

Sickles was promoted to major general in early January and assumed command of III Corps the following month. In early spring 1863, Sickles marched his corps with the Army of the Potomac into the heart of Virginia. In the Chancellorsville campaign, pickets from III Corps observed Confederate forces under LTG Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson on the march on 2 May. Sickles strongly advocated attacking the rebel column, but first needed to secure permission from his commander, MG Joseph Hooker. When MG Sickles finally received authorization for III Corps to attack, he led most of his command toward the tail end of Jackson’s column, taking a few hundred prisoners. While performing this maneuver, LTG Jackson launched his surprise attack against XI Corps’ open flank, forcing Sickles to march his forces back toward the rebel attack and battle the enemy in a bloody engagement.

Sickles’ final fight occurred at Gettysburg. Sickles’ III Corps arrived at the field of battle on 2 July 1863, receiving orders by MG George Meade to protect the Round Tops, the two hills anchoring the left flank of the Union lines. Without orders to do so, Sickles led III Corps over the Peach Orchard, creating a salient in the Federal lines that was quickly exploited by his adversary, LTG James Longstreet. During this action, III Corps suffered heavy casualties and was virtually destroyed. Sickles’ right leg was shattered by a cannonball and later amputated. In the battle’s aftermath, MG Meade, who advocated a defensive course of action at Gettysburg, blamed MG Sickles for this offensive debacle. Sickles preserved the leg he lost in the epic battle and later donated it to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C.

In the years following the war, Sickles would visit the museum to see his leg on the anniversary of its amputation. With his military career now over, Sickles continued pursuing his political aspirations. Traveling to South America in 1865, Sickles performed diplomatic assignments for the federal government. Later that year, Sickles became military governor of the Carolinas but was soon relieved of his office there by President Andrew Johnson.

In 1869, Sickles retired from the Army. President Grant appointed Sickles minister to Spain in May 1869. While serving in Spain, Sickles married his second wife, Carmina Creagh, and lived abroad with her for seven years. When Sickles finally returned to the United States, he did so without his wife and child beacause Carmina refused to come back with him. In 1886, he obtained the post of Chairman of the New York State Monuments commission, but he was eventually replaced many years later for mismanaging funds. Despite his old age, Sickles served in Congress from 1893 to 1895. In 1897, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Gettysburg. According to the citation, Sickles displayed “most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded.”

Separated from his family until they reunited with him while he rested on his deathbed, Sickles spent the last years of his life detached from reality and alone. Sickles died on 3 May 1914 at his home in New York. He now rests in Arlington National Cemetery.