By Matthew J. Seelinger, Chief Historian

5 June 2000 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the start of the Korean War. In June 1950, forces of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA), supported by a massive artillery barrage and strong armored forces, launched a surprise attack across the 38th Parallel in an effort to reunite the Korean peninsula by force. On 27 June, President Harry S. Truman ordered American forces to Korea to thwart the Communist invasion.

Most of the forces sent to Korea in the early days of the war came from the Eighth Army, which was performing occupation duty in Japan. Undermanned, and poorly trained and equipped, the American forces in Korea suffered grievous casualties while attempting to halt the NKPA onslaught. Among the first U.S. Army units deployed to Korea was the 24th Infantry Division.

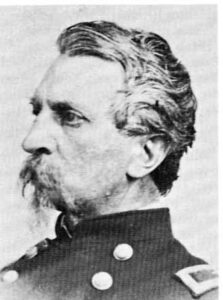

Led by MG William F. Dean, the 24th was comprised of largely untested, green troops. Lacking adequate numbers of heavy weapons, the soldiers of the 24th could do little more than delay the advancing North Koreans until more U.S. troops arrived. Inspired by their commanding general, the 24th stalled the enemy advance, but at a great price. MG Dean became one of the division’s casualties. The story of Dean’s courageous actions during the fighting around Taejon, his eventual capture by the NKPA, and his ordeal as a prisoner of war became one of the Korean War’s most intriguing stories and made Dean one the first heroes of the war.

William Frishe Dean was born 1 August 1899 in Carlyle, IL. After graduating from high school, Dean attempted to gain admission to West Point but was not accepted. He then tried to enlist in the Army during World War I, but because of his age, Dean needed his parents’ permission to enlist. His mother refused to grant permission, so instead, Dean enrolled in the University of California at Berkeley, and, determined to make the Army a career, joined the Student Army Training Corps. He graduated in 1922 and was later commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Infantry on 18 October 1923.

His first assignment was with the 38th Infantry at Fort Douglas, UT. According to Dean, this was during the period in which “practically nobody loved a soldier.” Despite the difficulties of serving in the peacetime Army, Dean proved to be a talented soldier, and he steadily advanced through the ranks. His assignments included a three year tour in the Panama Canal Zone and command of Camp Hackamore, a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, in Modoc, CA. He also attended the Infantry School at Fort Benning, the Command and General Staff College, the Armed Forces Industrial College, the Chemical Warfare School, and the Army War College.

After his promotion to major in 1940, Dean was assigned to a series of desk jobs on the War Department’s General Staff and in the Requirements Division in Ground Forces Headquarters. In early 1944, Dean, now a brigadier general, received an assignment he greatly wanted–assistant division commander of the 44th Infantry Division, which was preparing to deploy to Europe. Dean, however, almost did not make the trip. During a training demonstration, a lieutenant was engulfed in flames after the flamethrower he was using malfunctioned. In an attempt to rescue the soldier, Dean suffered severe burns on one leg. At one point, doctors believed the leg would have to be amputated. While the need for amputation subsided, Dean often required the use of a cane until the leg was able to completely heal after the war.

After arriving in the ETO on 15 September 1944, Dean demonstrated his ability to lead men in combat. In December 1944, he was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross after personally leading an infantry platoon through an artillery barrage to destroy enemy positions. After the 44th’s commanding general, MG Robert L. Spragins, was invalided home, Dean assumed command of the division and led the 44th in combat in France and Germany. When the war ended, the 44th held the distinction of having less than forty of its soldiers taken prisoner, an impressive number for a division that had seen a significant amount of combat. Dean was very proud of this statistic, later stating that “to say Kamerad was one of the most degrading things that could happen to a soldier.”

After the war, Dean was assigned to Fort Leavenworth to organize and direct new classes at the Command and General Staff College. In October 1947, he was sent to South Korea to serve as military governor and deputy to LTG John R. Hodges, commander of U.S. occupation forces in Korea. As military governor, Dean supervised the transition period in which the South Koreans learned to govern for themselves. His duties included oversight of police activities, food distribution, and operation of communication and transportation networks.

Dean’s primary duty, however, was the establishment of a civil government in South Korea. Having had no government of their own in many years and no freely elected government in their four thousand year history, the Koreans were “completely lacking in the machinery and training for holding an election.” In the months leading up the national election, Dean traveled throughout South Korea, making speeches, setting up election boards and polling places, and arranging protection for voters from coercion and Communist interference.

After the election, the U.S. occupation officially ended and the newly elected Korean government took over on 15 August 1948. Dean became commander of the 7th Infantry Division in Korea and immediately began arranging for the division’s withdrawal to northern Japan. After the 7th’s move was completed in January 1949, LTG Walton H. Walker appointed Dean as Chief of Staff of the Eighth Army. When a sudden transfer left the 24th Infantry Division without a commanding officer in October 1949, Dean managed to get himself appointed to the job. He set up his headquarters in the city of Kokura, on the southernmost Japanese main island of Kyushu, only 140 miles from Pusan across the Strait of Korea.

Despite his rank and bright future in the Army, Dean remained the modest and self-deprecating soldier he had always been. An avid walker, Dean would often refuse to ride in staff cars, preferring to walk whenever possible. The local Japanese nicknamed him Aruku Shoko, the “Walking General.” Aides recalled that he “had no hang ups about status” and that he was “his own best shoeshiner.”

On Sunday morning, 25 June 1950, Dean was heading towards the division headquarters when he was hailed by the duty officer with breaking news: North Korean forces had crossed the 38th Parallel. On 27 June, the 24th Division was assigned the task of receiving evacuees from Korea. The confusion of the evacuation was compounded by the fact that the Korean Military Advisory Group (KMAG) commander, BG Lynn Roberts, had completed his tour of duty and left on 24 June, and his chief of staff was in Japan.

Dean was ordered on 30 June to go to Tokyo to attend a meeting on the crisis, but he was intercepted near Hakata with instructions to return to his headquarters and await teletyped orders. The orders arrived at midnight directing Dean to prepare to move his division to Korea and giving him overall command of a land expeditionary force.

The proximity of the 24th Division to Korea, Dean’s combat experience, and his knowledge of Korea made him the logical choice to lead the initial U.S. ground force. Despite his abilities, there were numerous things Dean could not overcome. In particular, the 24th Division had been in Japan since shortly after V-J Day. Many of its experienced combat veterans had been discharged or transferred, and by 1950, only fifteen percent of the division’s soldiers had any combat experience. Overall division strength was at two-thirds of its World War II level. Infantry regiments contained two under-strength battalions each; artillery battalions had only two batteries. In addition to under-strength units, much of the division’s equipment was of World War II vintage–2.6” bazookas and M-24 light tanks. There were also critical shortages of mortars, ammunition, vehicles, and various other types of weapons and equipment.

Despite these problems, Dean received orders that a task force of two reinforced rifle companies from the 21st Infantry, with a battalion of field artillery, and the 21st’s Medical Company, was to be flown to Korea immediately. This unit, named Task Force Smith for its commander, LTC Charles B. (Brad) Smith, would be the first American force to face the North Koreans. In addition, Dean was to establish his headquarters at Taejon , an important communications center in southwestern South Korea. He arrived on 4 July and assumed command of American forces in Korea.

On 5 July the first American troops came into contact with the NKPA. Task Force Smith, emplaced in positions around the town of Osan, came under heavy attack by North Korean infantry and armored units. Smith’s troops put up a valiant defense and inflicted heavy losses on the enemy, but were eventually forced to withdraw. Because of poor communications, Dean originally believed that the task force had been completely wiped out. Over the next few days, however, American soldiers trickled back to the American lines. In all, about two-thirds of Task Force Smith survived, a far better result than Dean had originally believed.

For the next two weeks, the 24th Infantry Division fought a series of delaying actions that were intended to blunt the North Korean offensive and buy time for the rest of the Eighth Army to establish an effective defense around Pusan. These delaying actions were paid for with American blood; the 24th suffered over 2,400 casualties and lost large amounts of materiel in holding the North Koreans.

By 19 July, the NKPA had reached the South Korean town of Taejon. Dean had moved the division’s command post to Yongdong but stayed behind in Taejon at the 34th Infantry’s CP. During the early hours of 20 July, two divisions of NKPA infantry supported by tanks shattered and overran the 34th Infantry and the attached 2nd Battalion, 19th Infantry. The battle became confused as enemy infantry and tanks infiltrated into Taejon, cutting off American troops. Numerous small battles broke out all over the town as isolated American units fought desperately to escape the enemy trap.

With North Korean T-34 tanks roaming the streets of Taejon, Dean decided that there was “little general officer’s work to be done” and set off with his aide, 1LT Arthur M. Clarke, and Jimmy Kim, his Korean interpreter, on an almost obsessive hunt for enemy tanks. The party came first came across a group of three enemy tanks, two of which were destroyed. Dean managed to catch the attention of the driver of a truck with a 75mm recoilless rifle and ordered him to fire at the tank that appeared to be operable. The gunner fired several rounds but missed. It later turned out the tank had already been knocked out but showed no apparent signs of damage.

A second foray against the enemy also failed. Dean and his party found a bazooka gunner with one remaining round. The inexperienced gunner, suffering from nerves, fired short and never came close. Dean fired at the tank with his pistol out of frustration, something he later admitted was simply a case of “Dean losing his temper.”

A third attempt to destroy North Korean armor proved more successful. After the failed second attempt, a lone T-34 without infantry support rumbled through Taejon. Dean gathered a small hunting party and set off after the tank. Along the way, the group found a 3.5” bazooka gunner and his ammunition carrier. Locating the tank at an intersection in Taejon’s business district, Dean and the gunner crept through the back of a building until they were within yards of the tank. Dean pointed to a spot between the tank’s turret and hull and ordered the gunner to fire. After three direct hits, the tank was knocked out and began to smoke. Upon returning to the command post, Dean shouted, “I just got me a Red tank!”

By now, the situation in Taejong was hopeless, with the town all but overrun by NKPA troops. At around 1800, Dean ordered the evacuation of the 34th Infantry’s CP. Organized into a convoy of trucks and other vehicles, Dean and the remaining troops made a desperate attempt to reach American lines. Dean and Clarke made a wrong turn and became separated from the rest of the column. They eventually came upon another group of American troops, including many who were wounded. Dean ordered several of the wounded into his jeep and climbed aboard an artillery half-track that was, according to Dean, “the most heavily loaded vehicle I ever saw.”

Not long after the small column continued down the road, it ran into a North Korean road block. Dean ordered everyone out and into the hills. After taking an informal muster, Dean counted a total of seventeen soldiers and one terrified South Korean civilian who spoke English.

Dean’s group hid until dark before beginning the trek towards friendly lines. The journey was greatly hampered by the difficult terrain. In addition, several of the wounded men were unable to walk and had to be carried.

The difficult journey was made worse when the men quickly ran out of water. During one of their rest stops, Dean thought he heard water below the ridge where they were walking. In his attempt to locate the source, Dean stumbled down an embankment, hit his head, and knocked himself out. Clarke and the rest of the group, unable to find Dean in the darkness, decided to proceed south, reaching American lines on 23 July.

When Dean finally awoke, he discovered he had a deep gash on his head in addition to a broken shoulder. With dawn breaking, he crawled into some bushes to hide. As darkness fell, he emerged from his hiding place and started off once again for American lines.

While resting the following morning, Dean heard someone approaching. Thinking it was a North Korean patrol, Dean was surprised to discover that it was an American. The soldier identified himself as 1LT Stanley Tabor from the 2/19 Infantry. When Tabor asked who Dean was, Dean replied, “I’m the S.O.B. who’s the cause of all this trouble.”

The two continued their trek, occasionally meeting friendly Koreans who provided some meager food. While staying in a house in a small Korean village, Dean and Tabor awoke to discover the house surrounded by enemy troops demanding the two surrender. Instead of giving up, Dean and Tabor escaped out a rear door and fled into a rice paddy. Dean made his escape, but became separated from Tabor. Dean later learned after the war that the young lieutenant was captured after a few days and later died in a North Korean POW camp.

Alone once again and weakened by hunger and injuries, Dean slowly continued walking toward the American lines. Subsisting on green peaches, parched corn, and whatever handouts he could obtain from friendly Koreans, Dean lost sixty of his two hundred plus pounds during his ordeal.

By 25 August, Dean was approximately two days from the town of Taegu. His physical condition had improved somewhat and his spirits were buoyed as it seemed as if his wanderings were coming to an end. On that day, however, Dean was betrayed by two Koreans and turned into the NKPA. Despite his weakened condition, Dean did not succumb without a fight, and it took several soldiers to subdue him. After the war, South Korean police arrested the two men who turned Dean in to the NKPA. Both had received 30,000 won (the equivalent of five dollars) from the North Koreans. One was sentenced to death, the other to life in prison. Both men claimed that they had planned to take Dean to the American lines, but when this proved impossible, they turned him in to prevent his certain death. During the trial, Dean wrote to South Korean President Syngman Rhee asking for clemency for the two men, later saying, “I did not feel punishment of these men would accomplish anything.”

As a POW, Dean was taken to Seoul on the back of a truck and paraded through the streets. As the highest ranking U.S. prisoner of the war, he was subjected to endless interrogation, often lasting for days without end. He was threatened with torture and execution. On one occasion, one of his North Korean interrogators threatened to cut his tongue out. Dean replied that would have been fine, since then he would have been unable make propaganda broadcasts supporting the enemy.

He was kept isolated from other American POWs. Normally an active man, Dean was unable to exercise. In addition, medical treatment was virtually nonexistent. Yet, he remained unbreakable. At one point, he attempted suicide out of the fear that he might disclose important military information or make statements that might aid the enemy. On two other occasions, he made plans to escape, only to be held back by bouts of dysentery.

On 9 January 1951, while still listed as missing in action, Dean was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Truman for his gallantry in action at Taejon. Dean’s wife, Mildred, accepted the medal at a White House ceremony.

In December 1951, the North Koreans finally announced that they were holding Dean as a prisoner of war. The reason why the North Koreans waited so long to announce Dean’s capture has never been determined.

Throughout his captivity, Dean continued to resist his captors and never made any statements divulging important military information. He was finally repatriated on 4 September 1953 at Freedom Village. Upon learning that he had been awarded the Medal of Honor, Dean reacted with great dismay. While humbly grateful for the award, Dean felt he did not really deserve it. Upon meeting with reporters, Dean, in his typical self-deprecating style, stated that “I’m no hero. Anybody dumb enough to get captured doesn’t deserve to be a hero.”

After the war, Dean served as deputy commander of Sixth Army. In 1954, General Dean’s Story was published. The book detailed Dean’s experiences in Korea, both in combat and as a POW. He retired 31 October 1955 after 32 years of Army service and died in 1981 at the age of 82.

William F. Dean was one of the true heroes of the chaotic early weeks of the Korean War. He led his troops bravely in the face of overwhelming odds. While later criticized for his decision to stay at the front which hampered his ability to see the whole battle at Taejon, Dean did what he could with the resources at hand. More important, his inspired leadership by example in the burning streets of Taejon provided a boost to the shaky American morale. After his capture, he was a model POW. He survived three long years of captivity and resisted numerous attempts to force him into false confessions and propaganda statements. With a long and distinguished career in World War II and Korea, Dean exemplified the high ideals of the American soldier.

For more information on MG Dean and the Korean War, read MG William F. Dean, General Dean’s Story; Clay Blair, The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950-1953; Roy E. Appelman, South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu; James F. Schnabel, Policy and Direction: The First Year; and Marguerite Higgins, War in Korea: The Report of a Woman Combat Correspondent.