Written by: Fred L. Borch

“ … a lunar outpost … is of critical importance to the U.S. Army of the future.” It was March 1959, and Lieutenant General Arthur G. Trudeau, the writer of those words, was tasking Major General John H. Hinrichs, the Army’s Chief of Ordnance, to develop a proposal for a “manned lunar outpost” that would “protect potential United States interests on the moon.” The story behind this secret study, known as Project HORIZON, and the plan to put the Army on the Moon by 1966, is a strange but true story that today is very much forgotten.

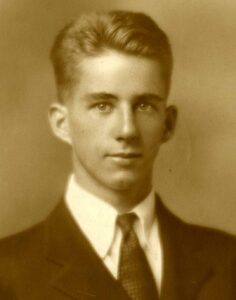

When Trudeau wrote Hinrichs, he had been the Army’s Chief of Research and Development for slightly more than a year. Trudeau had a reputation for being strongly anti-Communist and for advocating a strong national defense. In 1948, he arrived in Germany on the day of the Communist coup d’etat in Czechoslovakia and immediately recognized the Army’s difficult position in case of attack. He had also served as the Chief of Army

Intelligence after the Korean War. His twenty months in this position also convinced him that the Soviet Union presented a real danger to the United States and that winning the Cold War required America to have a “vigorous attitude” when it came to missile and weapons programs. This attitude only hardened when the Soviet Union shocked the world with the launch of the Sputnik satellite on 4 October 1957. It was bad enough that the Soviets had pulled even with the United States and its allies in nuclear weapons technology. Now, with Sputnik circling overhead, the United States was clearly behind the Russians in the so-called “Space Race.”

Given the increasingly tense Cold War with the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, it should come as no surprise that Trudeau and other senior Army leaders were thinking about the advantages of a military presence in outer space. An actual physical presence on the Moon would be the first step in the future of outer space military operations. It would not only give the United States Moon-based surveillance of the Earth and space but, once Moon-based weapons were in place, it could protect U.S. interests both on Earth and on the Moon. Additionally, the Moon almost certainly had raw materials that would give Americans valuable commercial advantages over every other nation. Finally, there was no way to know what sort of technological benefits would flow to the United States from scientific investigations and experiments conducted on the Moon.

There also were important intangibles to consider. According to the 118-page secret Project HORIZON study, submitted to the Department of the Army on 9 June 1959, “to be second to the Soviet Union in establishing an outpost on the Moon would be disastrous to our nation’s prestige and in turn to our democratic philosophy.” The Soviet Union had already proclaimed that its citizens—and presumably the Red Army—would be on the Moon in 1967, when the communist government in Moscow would be celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the October 1917 Revolution. This meant that it was imperative that the United States to get there first.

The goal of Project HORIZON was to produce a plan for building a self-sustained Moon base that would serve as an outpost for exploration of the Moon and further exploration of space. The base, which ultimately would house between ten and twenty personnel, would be the “first permanent manned installation on the moon” and, perhaps most importantly, would provide a platform for the Army, if required, to conduct “military operations on the Moon.”

The Army insisted that there were no known technical barriers to establishing a manned lunar base and believed that the base “should be a special project having authority and priority similar to the Manhattan Project in World War II.” After all, if America had designed and built the atomic bomb, there was no reason that it could not put a handful of soldiers on the Moon. Moreover, as both the United States and the Soviet Union recently had successfully launched animals (monkeys and dogs) into space on rockets, there was no reason to think that the first American manned lunar landing could not be achieved by 1965, with an outpost on lunar soil the following year. The experts involved in Project HORIZON were convinced that “advances in propulsion, electronics, space medicine and other astronautical sciences” were taking place at such an explosive rate that their proposed timelines for soldiers on the Moon was entirely realistic.

Project HORIZON contemplated using the 200-foot tall Saturn I and 300-foot tall Saturn II rockets, then under development by Wernher von Braun and his team of engineers, and ready for launch by the end of 1964. Both were multi-stage rockets and could propel thousands of pounds of construction materials into space. Engineers concluded that Saturn rockets would need to be launched from eight different terrestrial locations. Cape Canaveral would be one launch site, and the Panama Canal Zone (then under U.S. control) would be another, but launch pads in other countries would have to be built. Brazil was thought to be particularly attractive because of its geographical advantage on the equator. (Since the land at the equator is moving faster than land to the north or south, launching from the equator makes a spacecraft move much faster when it takes off, providing an extra “push” to place an object into orbit or beyond.)

The engineers working for the Chief of Ordnance proposed that some material should be sent directly to the Moon. A Saturn rocket would be launched into space, but it would not go into orbit around the Earth. Rather, it would proceed directly to the Moon and would land using “a retro-rocket or landing stage for the final landing maneuver.” The experts liked the “direct approach” idea of travelling to the Moon because it offered the shortest flight time from the Earth’s surface. The idea was to launch five Saturn rockets every month until “490,000 pounds of useful cargo” had been deposited on the lunar surface.

Army planners, however, also recognized that an alternative course of action would be to launch larger (and heavier) cargo payloads into space and then link them up with an intermediate assembly point: an orbiting space station. This was because the direct approach permitted only a 6,000-pound payload to be “soft-landed” on the Moon. Since the idea was to put 490,000 pounds of cargo on the Moon, this meant a lot of rocket launches. Consequently, an attractive alternative was to build a space station (only in existence on the drawing board) that could receive and accumulate payloads from the planned Saturn launches. After enough materials had been assembled at the space station, a space transport vehicle (also only on the drawing board) would ferry these virtually weightless payloads to the Moon. The Project HORIZON experts calculated that while each individual rocket could get 6,000 pounds directly to the Moon’s surface, a vehicle leaving the space station could “soft-land” a payload of 48,000 pounds.

The Army concluded that seventy-five Saturn II rocket launches could be achieved by the end of 1964, with cargo delivery to the Moon in January 1965. That would be followed by the first manned landing of two men on the Moon in April 1965; these two individuals, presumably soldiers or at least Army civilians, would supervise the “buildup and construction phase” of the outpost until it was ready for “beneficial occupancy” by a “task force of 12 men” in November 1966.

Studies further determined that rocket technology of the time limited the location of the base to twenty degrees latitude/longitude on the Moon. From this area, three sites were selected: the northern part of Sinus Aestuum, near the Eratosthenes Crater; the southern part of Sinus Aestuum near Sinus Medii; and the southwest coast of Mare Imbrium, just north of the Montes Apenninus Mountains.

As for the base itself, the scientists and technicians who took part in Project HORIZON insisted that their proposed base was “based on realistic requirements and capabilities;” it was “not an attempt to project so far into the future as to lose reality.” On the contrary, they wrote that their approach to the base was “a functional and reliable approach upon which men can stake their lives with confidence of survival.”

Recognizing that there was essentially no atmosphere on the Moon, and that surface temperatures ranged between 248 degrees Fahrenheit (lunar day) and minus 202 degrees Fahrenheit (lunar night), the scientists decided that the lunar base should be built underground. They suggested that natural “holes” or “caves” could be covered and sealed with pressure bags to create living spaces. This sort of construction also had the attraction of lessening the danger from meteorites. To power the station, the Army planned to send two nuclear reactors to the Moon that would provide power for both living quarters and construction equipment. The scientists also believed that solar energy would ultimately serve as an energy source for the lunar base.

Drawings in the study show a buried cylindrical structure that included living quarters, with an airlock to the surface. There would be a dining room, and planners insisted that once water supplies were adequate, “dehydrated and fresh-frozen foods” would be available. Ultimately, “attention will be given to hydroponic culture of salads and the development of other closed-cycle food product systems.” Presumably this meant that soldiers on the Moon would get their vegetables before too much time passed. There also was a recreation room in the outpost. Just what sort of recreation could be done is not clear, but given that the gravity on the Moon is one sixth that of Earth’s, there would have been limits; billiards and table tennis would have been problematic in any event. There also was a “medical hospital” and biological and physical science laboratories.

Oxygen and water would be extracted from the natural environment of the Moon. Military personnel stationed at the lunar base would wear space suits and carry special weapons and equipment developed expressly for Moon use. While the Project HORIZON study contained drawings of “typical lunar suit,” there was no discussion of what type of personal weapons the men would be carrying, much less what other types of other weapons would be developed and sent to the outpost. Given the Army’s development of the “pentomic division” in the 1950s (the 101st Airborne Division became the first Army unit to adopt the pentomic concept in 1956) for combat on the atomic battlefield, it is a near certainty that the Army contemplated that it would have atomic weapons in its new lunar outpost.

Another key feature was the plan to build a lunar-based communications and surveillance array. Communications on the lunar surface would be easy enough: “microminiaturized” two-way radios could be installed in individual lunar suits. A “Lunar Communications Net” would have to be established, however, so that soldiers who were out of sight of the outpost could communicate. The curvature of the Moon—and the fact that radios were line-of-sight—meant that a series of relay stations would have to be constructed. As for Moon-to-Earth (“Lunarcom” or Lunar Communications), this would easily be handled by using satellites in Earth orbit to relay radio traffic from the Moon to the Pentagon.

Project HORIZON was ambitious in its vision for soldiers on the Moon. The plan was to have 252 men in earth orbit by the end of 1967, with forty-two having continued on to the Moon for their tours of duty. Twenty-six of these soldier-astronauts would have returned from the Moon, stopping first at the orbiting space station before returning home to planet Earth. The Army planned for the men to do a tour of duty on the Moon that would not exceed one year.

As for who would be in charge of this new era in military history, the personnel working on Project HORIZON proposed that a “unified space command” be created to control the lunar base and “that portion of outer space encompassing the earth and the moon.” There seems little doubt that the Army leaders who had envisaged Project HORIZON saw an Army general as the perfect choice to lead such a unified command. Did Trudeau see himself as the first commander of this new space command? A 1924 U.S. Military Academy graduate, he had spent the first twenty-five years of his career in the Corps of Engineers before transferring to Armor in time for the Korean War. He was a proven leader, having volunteered for Korea, where he commanded the 7th Infantry Division and led it in battle at the T-bone, Alligator Jaws, and Pork Chop Hill. Trudeau himself was decorated with two Silver Stars for gallantry in action. One of those awards was for making a personal reconnaissance of Pork Chop Hill while this position was under heavy enemy fire. So perhaps Trudeau thought that he had the background to lead future military efforts in outer space, but it was not to be.

We must also look at a final point about Project HORIZON. Its proponents argued that America’s ultimate goal on the Moon should be to deploy Moon-based weapons systems. Why? Because Moon-based military power would be a strong deterrent to war since an enemy would have great difficulty in preventing U.S. retaliation. This was because the enemy—likely the Soviet Union but perhaps also Communist China—would have a hard time reaching the Moon and, if American forces were already present, they could counter or neutralize any hostile force that might land. This was also the reason that American military forces needed to reach the Moon first and establish a military outpost, since the enemy could counter any U.S. attempt to land on the Moon “if hostile forces were permitted to arrive first.”

Looking back over more than half a century at Project HORIZON, the most obvious question is why the Army thought that it should be involved in space operations. At that time, the Air Force had been independent from the Army for only twelve years and, as yet, was not viewed as having any sort of monopoly on air and space (other than the delivery of nuclear weapons by strategic bombers and missiles). As a result, there was no reason for the Army to refrain from planning Project HORIZON. As for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, it had only been organized in 1958 and, as a civilian organization, would never be able to deal with national defense matters in the way that the Army could—or was required to do by the U.S. Constitution. After all, Lieutenant General Trudeau and other senior Army officers were thinking about building a military outpost that, except for its location on the Moon, would be no different from any other post, camp, or station that the Army might construct on Earth.

We know today, however, that this concept for an Army base on the Moon did not happen. Why not? There were at least three reasons. First, the technological challenges were more difficult than the authors of Project HORIZON had thought—and also considerably more expensive. An effort similar in scope of the Manhattan Project might have worked, but it would have required a huge increase in the federal government’s expenditures on defense. The idea was to spend $6 billion over eight and one-half years ($700 million per year). When one remembers that the federal minimum wage in 1958 was $1.00 per hour, this was a huge sum of money that would have required a significant increase in taxes. In any event, as the alarm over Sputnik dissipated, there was diminishing political interest in funding a military base on the Moon.

Second, the expansion of the war in Vietnam also siphoned off energy—and funds—that might have gone to Project HORIZON. President John F. Kennedy had pledged to put a man on the Moon; his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, was more interested in domestic politics, including a war on poverty and his Great Society programs, although he ultimately was consumed by the war in Southeast Asia.

Third, and most importantly, any future American military presence on the Moon became an impossibility when the United States, Soviet Union, and United Kingdom signed an outer space treaty in 1967. While Lieutenant General Trudeau and other senior leaders in the Pentagon might have been certain that a lunar outpost was critical to the future of the Army, others in Washington were less sure. Since the United States had “lost” the race to put the first satellite in orbit, how could the White House be certain that America would win the space race to the Moon? What if the USSR put a base on the Moon first, or at the same time? What sort of territorial claims might the Russians make, and would these conflict with U.S. claims? What sort of occupation of the lunar surface would be needed for a country to claim some or all of the Moon as part of its national territory? No one in the White House or the State Department could be certain.

An even bigger issue was the militarization of the Moon. There is no doubt that Trudeau and others in uniform contemplated that conventional weapons would be on the Moon with soldiers, but what about nuclear weapons? The Limited Test Ban Treaty, signed in 1963, prevented atomic weapons from being test detonated in outer space. This agreement did not, however, prevent the United States or any other nuclear power from putting atomic weapons on the Moon. But was this sound policy? What if a conflict were to break out on the Moon between lunar settlements? Could it escalate to a nuclear exchange on Earth?

In the end, there were too many unknowns, and the risks were too high. It should be noted that a similar study by the Air Force, known as the Lunar Expedition, or LUNEX, Project, to establish an Air Force base on the Moon met a similar fate. The proverbial “nail in the coffin” for a military installation on the Moon came in 1967, when the United States, Soviet Union, and United Kingdom signed an international agreement limiting the use of the Moon to peaceful purposes. The Outer Space Treaty, known formally as the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, prohibited nuclear weapons (or any weapon of mass destruction) from being placed in orbit around the Earth. It also prohibited military equipment on the lunar surface unless the equipment was for entirely peaceful purposes. In short, the militarization of the Moon was no longer an option, and it remains an impossibility since this international treaty is still in effect.

It took until 1969 before a man—astronaut Neil Armstrong—would take a giant leap for mankind on the surface of the Moon, but there is still no base of any kind on the Moon. While Project HORIZON is largely forgotten today, it remains an idea whose time simply never came—and a strange but true story in Army history.